Mais uma colaboração antiga do Gustavo Prado que coloco agora no ar só agora. Para ver todas as colunas do Gustavo basta clicar GP/NY na aba das categorias aí ao lado.

)

Alegria!

Ontem Mariana me levou para assistir ao documentário de Wim Wenders sobre Pina Bausch, e por mais que eu não saiba avaliar se há nele uma real inovação sobre a forma de filmar dança, não me lembro de ter jamais assistido um uso tão necessário dos recursos 3D em cinema. Perto da forma com que foi usado em Pina, outras aplicações até aqui, são meras anedotas e adereços, um toque monótono, monocórdio, do susto ou da vertigem.

Quero ser capaz de escrever mais para frente algo mais apropriado sobre o filme, que me tocou profundamente, sobretudo, por me fazer compreender um pouco melhor a dimensão e a importância de Pina. Estranha essa sensação de querer conversar com alguém que não faz parte do seu tempo, tenho que parar de sentir isso, essa semana tentei ligar para o Manet e ninguém atendeu, agora fiquei pensando em escrever para Pina, mas há que se ter limite.

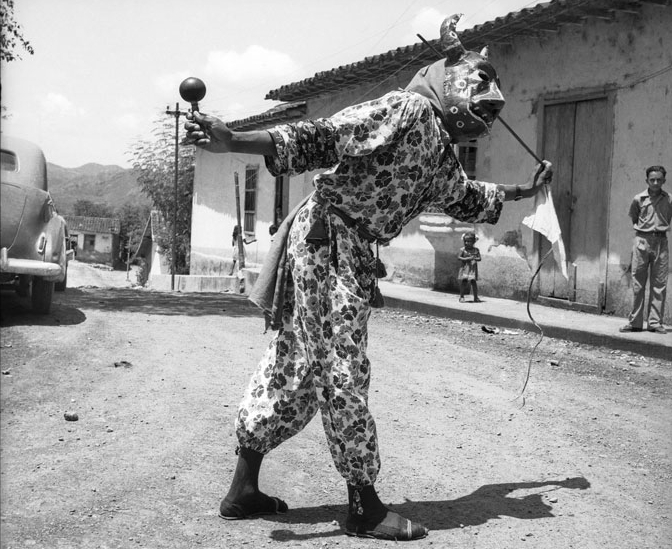

Impressiona muito a capacidade dela, de pensar do mais profundamente triste e trágico, ao mais engraçado e alegre. É bonita a forma com que o filme apresenta o uso que ela faz de seus bailarinos, a capacidade que ela tem de incorporar às suas narrativas um pouco das origens, dos sentimentos e da identidade de quem dança para ela. Esse vídeo que escolhi, é um dos exemplos mais bonitos disso no filme. E me fez pensar no sentido de expressão, que já se tornou há muito tempo um chavão, um lugar-comum que é usado com tanta banalidade na forma de se abordar uma obra de arte, por ser quase sempre a descrição de um processo dramático no qual o artista expurga seus sentimentos íntimos pela obra. Eca! Coisa cafona, que todos nós já ouvimos tantas vezes, principalmente quando se trata de um solista, de um ator ou de um pintor, que são, supostamente, atividades artísticas mais vinculadas a um certo sentido de individualidade, de autonomia, e com isso – de “expressividade”. Pois bem, no caso desse bailarino, o que poderíamos preguiçosamente chamar da sua forma de expressar uma alegria, é colocado com tão maior interesse e inteligência, num momento valioso do filme, em que passamos a conhecer mais sobre o processo dela.

Ele diz que Pina os colocou uma pergunta, sobre como seria um movimento relacionado a alegria, ou ânimo em movimento, logo em seguida, você ouve ele dizer, num espanhol tão bonito, que era uma pergunta linda! E esse é o ponto, um dançarino trabalha a clareza, gestos largos ou miúdos, que devem dizer tudo, mas não por um desejo indefinido de expressão, mas como a resposta que encaixa na beleza de uma pergunta. É uma dúvida, mas ao mesmo tempo um comando e uma direção, ela diz – responda, mas também diz –investigue, busque. E tudo isso, mais do que ser desfocado como parte do gesto generalizante que seria chamar a resposta dele de expressão, tem, na verdade, a ver com escolhas, com afunilar o possível até encontrar o próprio, mais do que o apropriado, o preciso, o que é preciso para que seja certo, para que mais do que a beleza da pergunta, seja o assombro da resposta. E com os olhos escancarados nos dizemos baixinho – sim essa é a alegria, eu quero é dessa, já que ela pode ser assim!

Há naquela alegria, uma invenção, um jogo novo, pois, é claro que não há um mundo de idéias em que a forma eterna da alegria esta protegida das sombras da realidade, não é nada disso! A alegria vai sendo inventada por todos que foram e serão alegres um dia, por velhos e novos motivos. Aquela alegria é uma alegria corpo, uma alegria para músculos e música, e só é imensa porque é dele, e amplia o campo da dança e da alegria por ser uma alegria-dança. Portanto, o que ele trabalha com uma capacidade de síntese e precisão absurdas é na transformação dessa idéia ou desse sentimento em forma, em estrutura, em cadência, ritmo, e esses passos que parecem tão fáceis e intuitivos só o são, graças a muito trabalho.

E para responder a pergunta da alegria é preciso tornar o corpo leve e os olhos altos, os passos largos como saltos tolos, tem que ser uma alegria plena de orgulho, de quem encontra um lugar para si no mundo e cabe nele sem quinas ou apertos, é alegria de quem não perdeu a infância e carrega o menino que é si mesmo no colo, coisa de neto gaiato, da bobeira boa que só uma alma quente é capaz de sentir. Há que se ter ginga, ter a inteligência de um Romário, ser um pouco leviano, muita preocupação vira âncora e joga pro chão. Não! Tem que ser uma alegria que tenha cara de carnaval, tenha brincadeira e deboche, de inicio das férias, de quem corre para mergulhar no mar, de quem acaba de beijar na boca depois de despedir no portão quando ainda não se sabe trepar e aquele beijo é tudo o que se conhece sobre amar alguém. Alegria de ter um filho. De vê-la saindo do portão no aeroporto, de quando a saudade acaba porque já chegou a hora de estar perto. Claro que isso tudo sou eu brincando com texto por não saber brincar com os braços, com as pernas e com o corpo. Tentando dar alegria ao texto, ou inventando dele uma alegria minha.

Mas o ponto é: – dá para trocar tanta imaginação e brincadeira, tantas decisões que só se tornam resultados, quando o corpo se prepara para ser tão imediato, forte e veloz quanto o estalo de uma idéia, – por chamar tudo isso de expressão? Ah não! A preguiça é inimiga da invenção. E chega de preguiça, pois se foi possível haver Pina, não há tempo a perder!

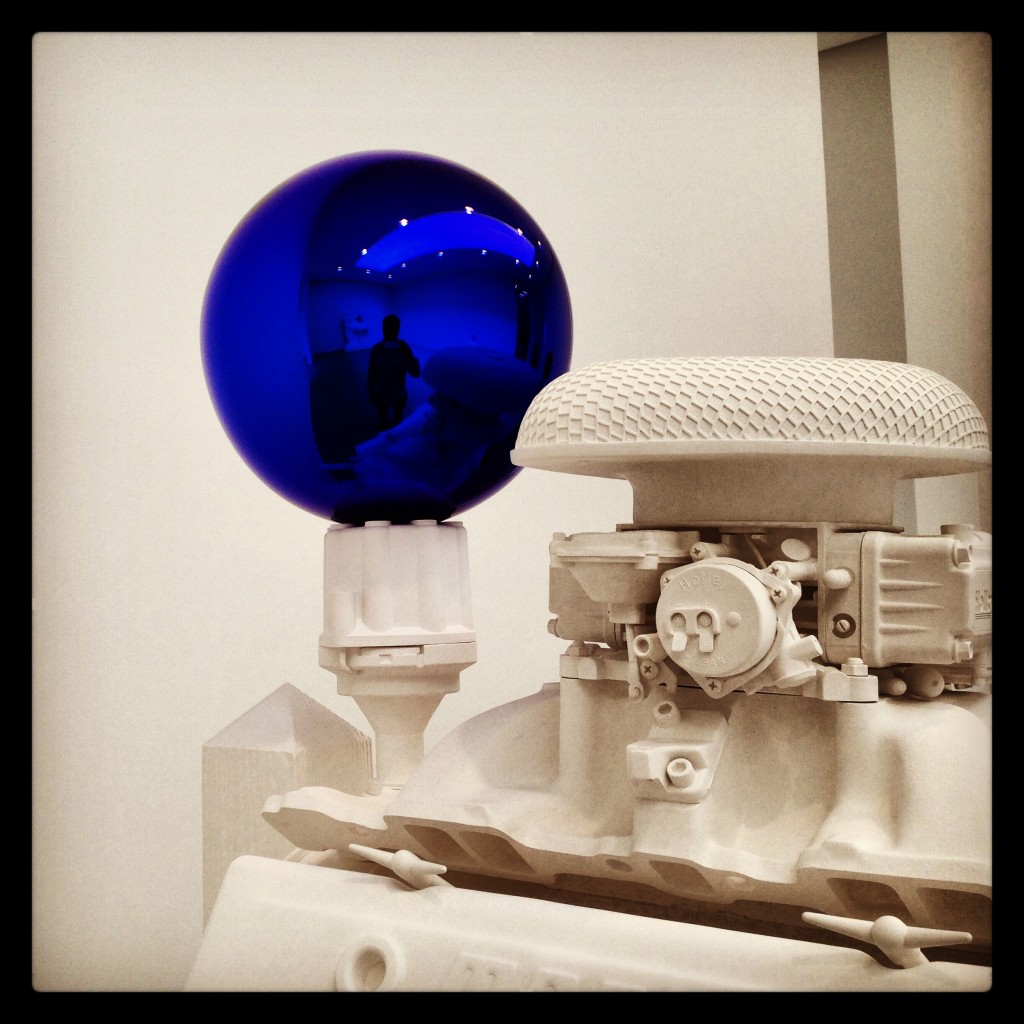

Photograph: David LeveneLucas goes from bad girl to terrific sculptor in this rumbustious, raunchy and inventive tour of old works and new. Her show went from the bawdy and abject to the delicate and the monumental. Vulnerability, sensitivity, humour – she’s got the lot.

Photograph: David LeveneLucas goes from bad girl to terrific sculptor in this rumbustious, raunchy and inventive tour of old works and new. Her show went from the bawdy and abject to the delicate and the monumental. Vulnerability, sensitivity, humour – she’s got the lot. With

With  Photograph: Juergen TellerA riot of fashion shoots and landscape shots, public parade and private moments. Teller treated his back catalogue as material in this cascade of portraits and situations, a collision of people and worlds. The images keep on coming.

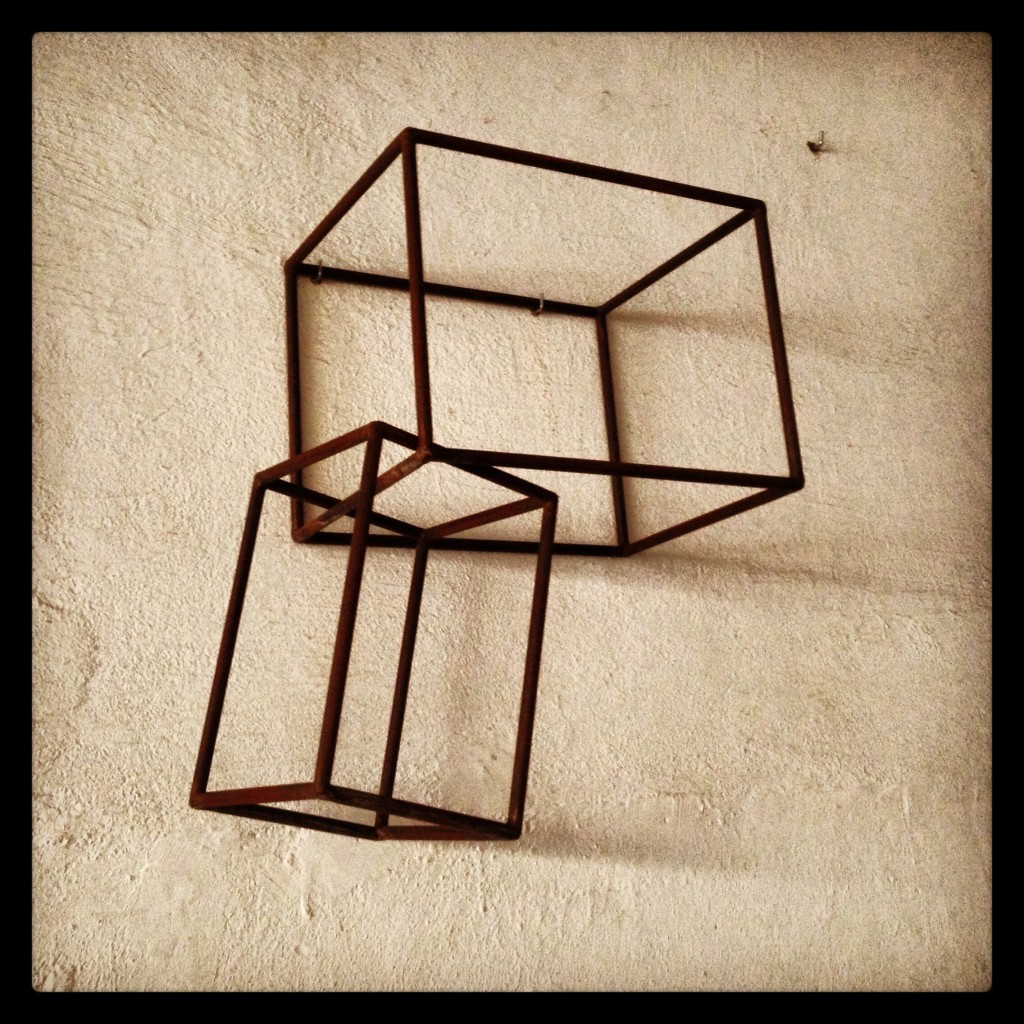

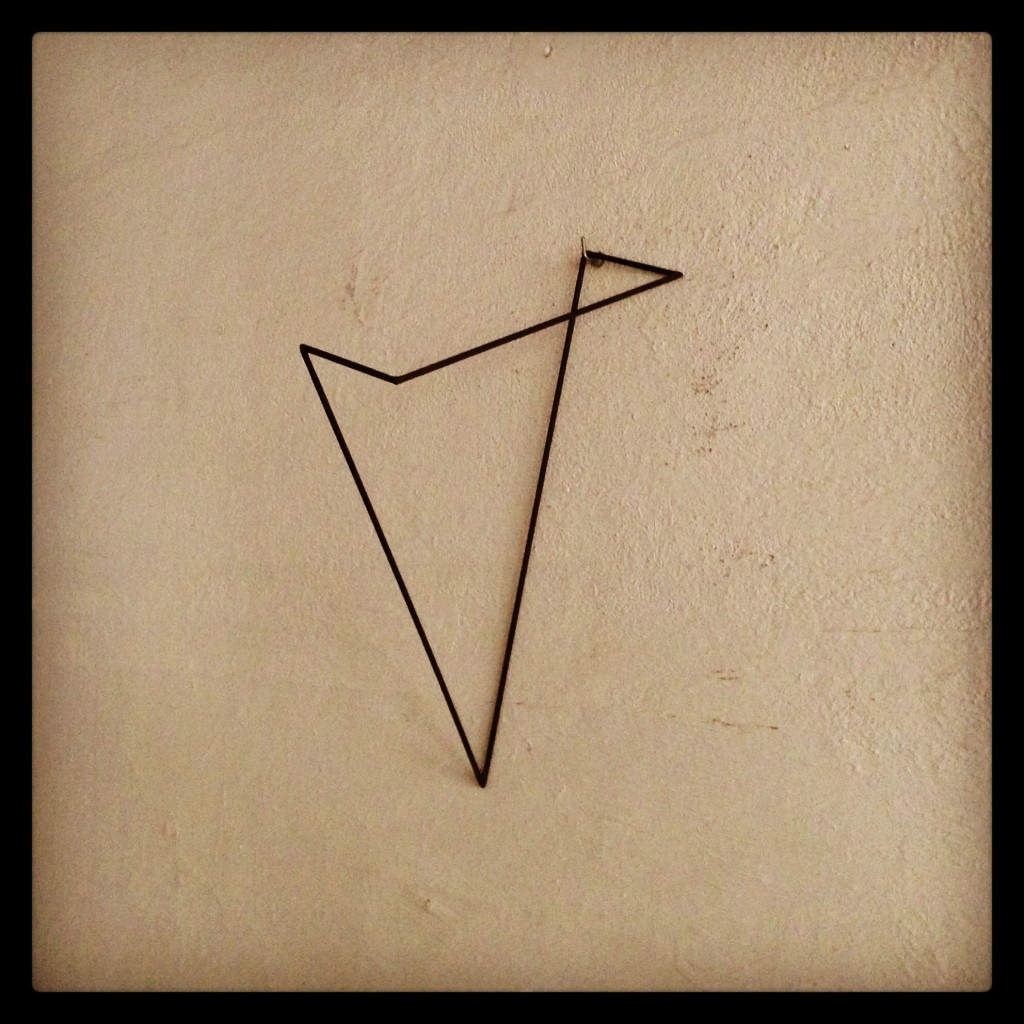

Photograph: Juergen TellerA riot of fashion shoots and landscape shots, public parade and private moments. Teller treated his back catalogue as material in this cascade of portraits and situations, a collision of people and worlds. The images keep on coming. This reconstruction of the seminal 1969 Bern Kunsthalle exhibition of arte povera and conceptualism, relocated inside a Venetian palace, played games with time and space. I was swept away by the art itself – from Mario Merz to Bruce Nauman – and by Thomas Demand and Rem Koolhaas’s restaging of the original show.

This reconstruction of the seminal 1969 Bern Kunsthalle exhibition of arte povera and conceptualism, relocated inside a Venetian palace, played games with time and space. I was swept away by the art itself – from Mario Merz to Bruce Nauman – and by Thomas Demand and Rem Koolhaas’s restaging of the original show.