MC LDN #10

Maria do Carmo Pontes, a correspondente avançada do b®og em Londres (com foto e micro-perfil aí na barra lateral), mandou a décima coluna MC LDN diretamente de Paris… Lá vai:

Huyghe & Parreno

Giovana Maria Sebastian. À porta da exposição do Pierre Huyghe, no Beaubourg, em Paris, um homem anunciava a entrada de cada um dos visitantes pelo primeiro nome, introduzindo uns aos outros e, a todos, a teatralidade da mostra. Concebida como uma retrospectiva de meio de carreira do artista francês, a exposição reúne trabalhos produzidos nos últimos 20 anos, como o belíssimo Recollection (2011). Este consiste num aquário com um caranguejo-ermitão (espécie que vive em conchas de caracóis abandonados) que se apropriou de uma reprodução oca da Sleeping Muse (1908), de Brancusi, e fez dela sua casa; por onde quer que o caranguejo vá, ele carrega consigo a icônica cabeça da musa. A mostra conta ainda com performances ocasionais e outros trabalhos marcantes da carreira do artista, como obras da série Untilled (sic), apresentadas inicialmente na dOCUMENTA 13 (2012), e No Ghost Just a Shell (1999-2003), em parceria com o Phillipe Parreno, que oferece o uso da imagem da mangá Annlee (adquirido pelos artistas) de graça para outros artistas criarem obras com a boneca. Para além de trabalhos individuais, a mostra prima pela maneira como os encadea, colocando grande ênfase no pano de fundo da exposição, isto é, a arquitetura. Essa estratégia é radicalizada na mostra Anywhere, Anywhere Out of the World, de Phillipe Parreno, não por acaso em cartaz ao mesmo tempo que a mostra de Huyghe, no Palais de Tokyo, também em Paris. Parreno respondeu de forma sagaz ao convite de ocupar integralmente o espaço do Palais, criando uma coreografia de luz e som cujo alcance excedia a própria fisicalidade dos materiais, perpassando as salas do museu. Porões e outros ambientes que não são comumente abertos para exposições estavam acessíveis, orquestrando um verdadeiro labirinto que por vezes levava a becos sem saída. Ocasionalmente os visitantes encontravam obras, tanto de Parreno quanto de outros artistas da gang: Huyghe, Tino Sehgal, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster – cuja estante falsa La Bibliothèque Clandestine (2013) esconde uma sala secreta contendo desenhos de Merce Cunningham e John Cage, poderosíssimos em sua ingenuidade – entre muitos outros. Foi emocionante me perder pelas entranhas do museu, me deparar com trabalhos como Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait (2006), de Parreno e Douglas Gordon, que eu tive o prazer de ver pela primeira vez as 17 projeções ao mesmo tempo. Cada um a seu modo, Huyghe e Parreno conceberam exposições surpreendentes onde, em ambos os casos, o meio é a mensagem.

CRISTÓBAL LEHYT: “IRIS SHEETS II: THIS TIME IT’S PERSONAL” @ Johannes Vogt Gallery

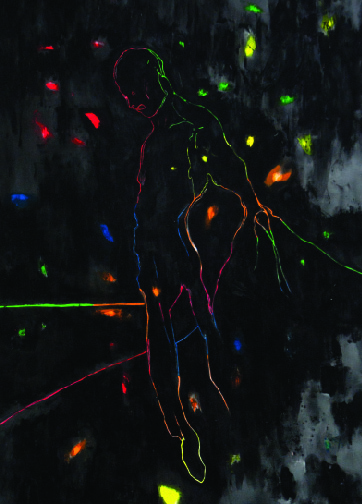

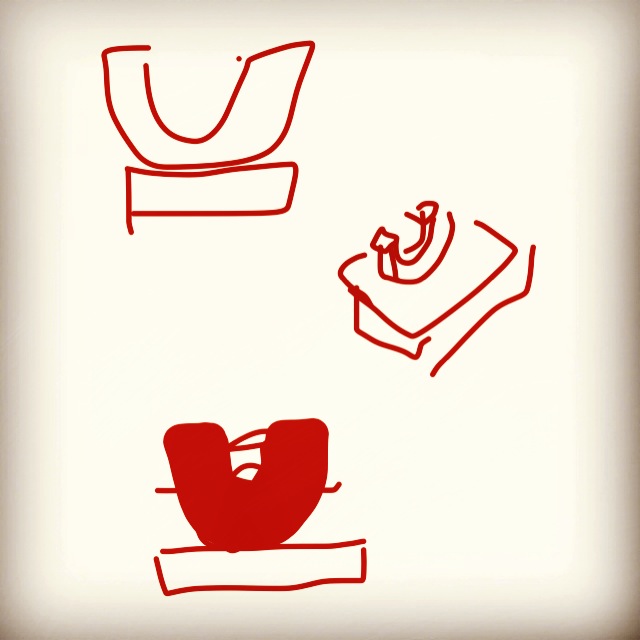

Johannes Vogt Gallery is pleased to announce the second solo exhibition of Cristóbal Lehyt. The show, linked to his current exhibition “Iris Sheets” at Americas Society New York, will present the newest manifestations of the Drama Projection series, including acrylic on polyester, wall painting and pencil or inkpen on paper. For the first time, a survey of the original drawings will be displayed, allowing a comprehensive understanding of the process entailed in the series.

The Drama Projection series expands on the topic of re-staging identity, figuration, and drama in opposition to narrative. Original figurative drawings are created through quick visual responses and repetition. Through mediated processes, the traditional human subject is altered into a series of repeatable signs. These signs gain meaning through translation into a range of media, such as crayon drawings, inkjet prints, paintings, and drawings executed directly on the wall.

For this second exhibition at the gallery, Lehyt places the figures of the Drama Projection series within a group of large-scale paintings on polyester that are presented unstretched and floating on the wall. In these works, mysterious figures appear born out of fluorescence echoing several moments in the development of an individual, from child night lights to party decorations. Within the structured gallery space, the strange effects of these neon colors take on a seemingly narrative structure that is estranged from any specific plot: actors in different stages. Among the paintings is a single drawing executed directly on the wall, appearing as an image but embedding itself into the architecture.

In the rear gallery, an extensive selection of original drawings dating from 2003 to today amplifies the vivid contrast between form and space. The selection of drawings – both the source material from which these figures are reproduced, as well as crayon etchings – span the last decade of the artist’s production.

The Drama Projection series evolves into a theatrical stage engaging the viewer’s psychological self. In this theatrical positioning, and by investing in the historical and visual weight of painting-as-medium, the presentation questions what painting can be now, what possibilities the discourse of painting allows for a meaningful connection with its audience.

Cristóbal Lehyt was born in Santiago, Chile, in 1973. He lives and works in New York. His work has been shown internationally, including the Kunstlerhaus Stuttgart, the Shanghai Biennale, the Mercosul Biennial, the Queens Museum, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. Lehyt currently teaches both at Cooper Union and Parsons, New York. He has been awarded the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship and the Art Forum Fellowship from Harvard University. Lehyt is included in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and the Museo de Arte Contemporaneo, Santiago, Chile. His solo exhibition Iris Sheets is currently on view at the Americas Society, New York through December 14.

Hours: Tuesday – Saturday, 11 am – 6 pm and by appointment. For further details please contact

Samuel Draxler at samuel@vogtgallery.com or at 212.255.2671

Obra de Palatnik bate recorde em leilão da Christie’s

‘Sequência Visual S-51’ foi arrematado por US$ 785 mil, o triplo da estimativa mais alta, em evento terça e quarta

Os especialistas da casa de leilões Christie’s acertaram na avaliação das obras que participariam de evento promovido anteontem e ontem: as peças atingiram o preço mais alto no leilão de arte latino-americana. Women Reaching for the Moon, do mexicano Rufino Tamayo (1899-1991), óleo sobre tela de 1946 e com preço estimado entre US$ 1,2 milhão e US$ 1,8 milhão, foi vendido por US$ 1,445 milhão. Já O Casamento (1995), quadro de acrílica sobre tela da brasileira Beatriz Milhazes e avaliado entre US$ 600 mil e US$ 800 mil, saiu por US$ 1,025 milhão. Os valores incluem a comissão da casa.

Mas ninguém esperava o resultado obtido pela obra cinética de Abraham Palatnik. Sequência Visual S-51, trabalho produzido pelo artista brasileiro na década de 1960, foi arrematado por US$ 785 mil, o triplo da estimativa mais alta que lhe deram, e ficou em quarto lugar na lista dos dez lotes com os maiores preços pagos no leilão.

Comprado por um galerista sulamericano, Sequência Visual S-51 marcou recorde de preço para obra de Palatnik em venda pública. Antes, o valor mais alto alcançado por uma obra dele em leilão foi para Progressão 42-A, de 1965, quadro vendido dois anos atrás na Sotheby’s por US$ 182,5 mil. Palatnik, de 85 anos, foi um dos participantes da primeira bienal de arte realizada em São Paulo, em 1951, onde mostrou, pela primeira vez, trabalhos cinecromáticos semelhantes ao que foi leiloado na Christie’s. Feito como uma caixa de madeira coberta por tecido sintético, Sequência Visual S-51 explora questões relativas à pintura criando movimentos e cores por meio de lentes, lâmpadas e um motorzinho.

Nos últimos anos, artistas brasileiros contemporâneos e na faixa dos 40 e 50 anos de idade têm seus nomes incluídos com frequência em listas de recordes. Mas no leilão da Christie’s, além de Palatnik, quem também teve obra com recorde de preço em venda pública foi a japonesa naturalizada brasileira Tomie Ohtake, que completa cem anos de idade esta semana. Um óleo sobre tela sem título, pintado com seus característicos tons de vermelho em 1979 e avaliado entre US$40 mil e US$60 mil, foi arrematado por US$ 81.250; segundo informações da Christie’s, o recorde anterior para obra de Tomie em leilão era de Botão, óleo sobre tela de 1979 que foi vendido num leilão no Texas, em 2009, por US$ 41.825.

Entre os cerca de 200 lotes de arte latino-americana que a Christie’s leiloou em sessões na terça-feira à noite e hoje, 30 eram obras brasileiras que ganharam destaque numa brochura separada do catálogo do leilão. O empenho na captura de trabalhos com apelo internacional rendeu a inclusão também de Relief Nº 285, de Sérgio Camargo (1930-1990) na lista dos dez lotes vendidos pelos preços mais altos. A construção de madeira pintada de branco e executada em Paris em 1970, com estimativa entre US$ 500 mil e US$ 700 mil, saiu por US$ 749 mil.

Outros lotes arrematados pelos valores mais altos no leilão da Christie’s foram: La Rose Zombie, óleo sobre tela de 1950 do cubano Wifredo Lam, com estimativa de preço entre US$ 500 mil/US$ 700 mil e vendido por US$ 845 mil; a pintura Dos Mujeres en Rojos (1978), de Rufino Tamayo, avaliado entre US$ 600 mil/US$ 800 mil e arrematado por US$ 665 mil; La Rosa (1943), do chileno Matta, avaliado entre US$ 250 mil/US$ 350 mil e vendido por US$ 461 mil. Completam a lista o quadro Navío Constructive (1934), de Joaquín Torres-García, arrematado por US$ 425 mil; outro óleo sobre tela de Matta pintado em 1960, que alcançou US$ 425 mil; e com preço igual a este um outro Tamayo, Child Playing (1945).

A Christie’s fechou as contas de seu leilão em US$ 18,2 milhões.

Texto de Tonica Chagas publicado no Jornal O Estado de S. Paulo | 20/11/13

Christian Marclay @ Paula Cooper

New Paintings and Works on Paper

November 22 – January 18, 2014

534 W 21st Street

Christian Marclay, Actions: Plish Plip! Plap!!! Plop…(No.2), 2013; screenprint with hand painted acrylic, 37 7⁄8 × 49 in.

NEW YORK – The Paula Cooper Gallery is pleased to present an exhibition of new paintings and works on paper by Christian Marclay. The exhibition, which will be on view at 534 W 21st Street, opens on November 22nd.

This new group of works consists of silk-screen on painted backgrounds, featuring onomatopoeias that evoke the sound of painting actions (SPLORCH! SLLURP! WHOOMPH!). Torn from comic book pages, collaged, blown up and printed on canvas and paper, the onomatopoeias extend Marclayʼs investigation into the relationship between sound and image, sampling elements from art and popular culture. As in his music and video works, which splice together found recordings and film footage, the comic book sound effects are recontextualized in vibrant, dynamic compositions. Swirling, acqueous text and color combine mimetic words with puddles and splatters across the surface, conflating the painted and the printed in a surprising mix.

Marclay began silk-screen printing in 2006 for a body of work based on a detail from Andy Warhol’s famous Electric Chair image from his Death and Disasterseries. The paintings on view also relate closely to Marclay’s vocal score Manga Scroll (2010), part of a body of work incorporating onomatopoeias clipped from Japanese Manga and American comics. Like his earlier “graphic” scores, which employ non-traditional visualizations of sound as possibilities for generating music, the new paintings present arrangements of sonic text that interact with the painterly gesture. Chance operation and playful irony underscore Marclay’s Cageian influence as well as an engagement with the history of painting.

Christian Marclay (b. 1955, San Rafael, California) grew up in Geneva, Switzerland. His work has been shown at international venues including the Museum of Modern Art; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C.; Musée d’Art et d’Histoire, Geneva; Kunsthaus Zürich; Tate Modern, London. In 2011, he received The Golden Lion for his presentation of The Clock at the Venice Biennale. The work has since traveled to numerous venues internationally. In 2010, the Whitney Museum of American Art organized a one-person exhibition titled “Festival.” In 2004, the UCLA Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, organized a midcareer retrospective, which traveled to France, Switzerland, and Great Britain. Marclay lives and works in New York and London.

For more information, please contact the gallery at (212) 255-1105, or info@paulacoopergallery.com

Artist Pages: Christian Marclay

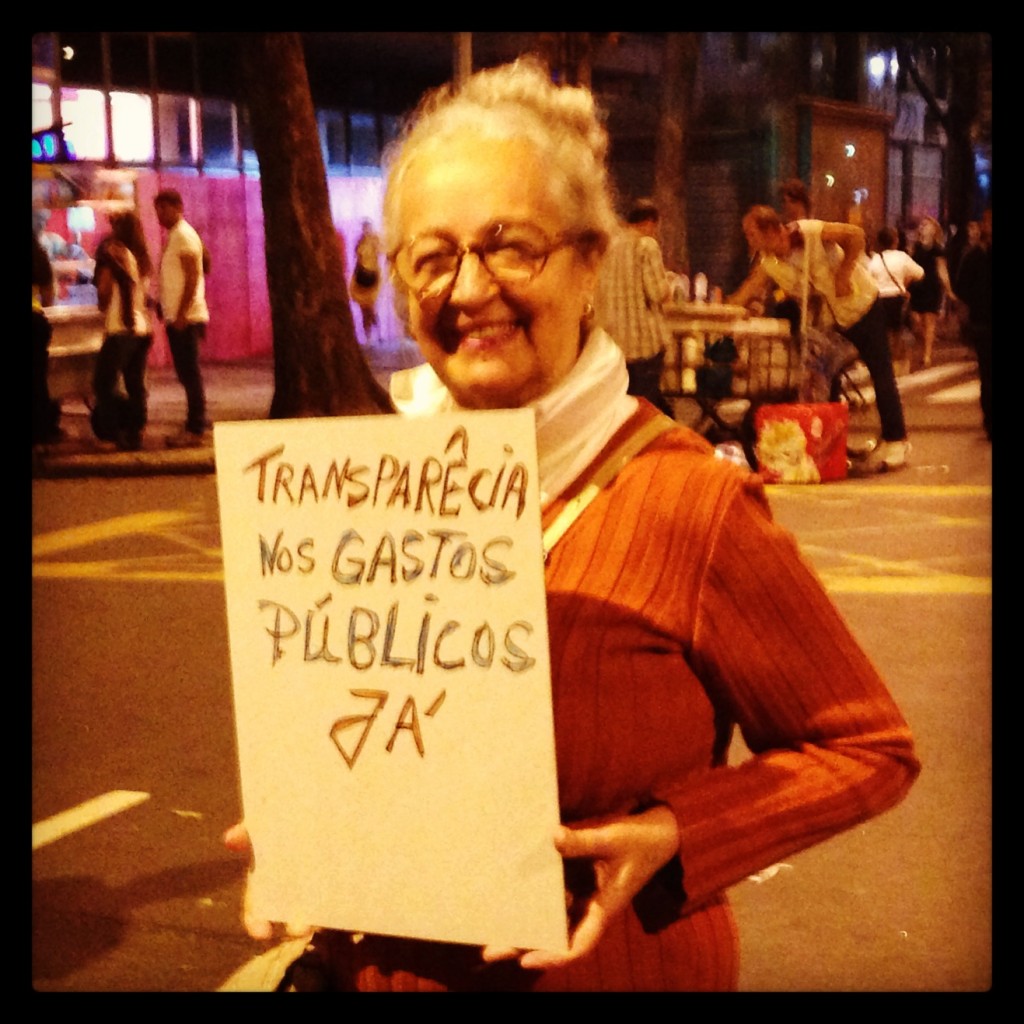

TIMELINE #9 (rio-sp-brasilia-rio)

Fakers, Fakes, & Fake Fakers by Milton Esterow

BY Milton Esterow POSTED 11/20/13

Well-known forgers reveal the creative methods they use to copy the masters

Many years ago, I interviewed a forger named David Stein. He had been arrested for faking hundreds of drawings, gouaches, and watercolors by Matisse, Chagall, Picasso, Cézanne, Degas, Miró, and many others. One day, while he was out on bail, I asked him how an art forger creates works by well-known artists whose styles are so different.

“The first thing you have to do is know intimately the artist you are imitating, not only to know him but also to like him, to love his art,” Stein said. “You go into the soul and mind of the artist. It’s like a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde thing. You become someone else. When I painted a Matisse, I became Matisse. When I painted a Chagall, I was Chagall. When I painted a Picasso, I was Picasso.”

Art forgery has been a hot topic lately since the disclosure that Pei-Shen Qian, a 73-year-old immigrant from China, working out of his home in Queens, reportedly created at least 63 drawings and paintings by Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, Barnett Newman, Franz Kline, and Richard Diebenkorn.

The works were sold or consigned by Glafira Rosales, a dealer of Sands Point, New York, to two Manhattan dealers, Knoedler & Company, which closed in 2011, and Julian Weissman. Over a period of 15 years, the works were sold to collectors for about $80 million. Knoedler, its former presidentAnn Freedman, and Weissman have consistently stated that they were convinced that the works were authentic. Freedman says she showed the paintings to a number of experts, who confirmed the authenticity and quality of the works.

The case against Rosales is known as United States of America v. Glafira Rosales, a/k/a “Glafira Gonzalez,” a/k/a “Glafira Rosales Rojas,” defendant. She pleaded guilty in September to charges of wire fraud, money laundering, and tax evasion. As we went to press, no one else had been charged in the case, but Assistant United States Attorney Jason P. Hernandez indicated that additional arrests were contemplated.

Qian is said to be back in China, where he exhibited his own paintings in May at the Xiang Jiang Gallery in Shanghai. He has also had shows at the BB Gallery in Beijing. Qian came to the United States in the 1980s and studied at the Art Students League in New York. According to the website of the Shanghai gallery, one of his teachers was Richard Pousette-Dart.

Zhang Hongtu, a prominent Chinese artist who lives in Queens, told me, “I couldn’t believe he would do this to fool the art market. I met him in 1982 and last saw him about 20 years ago. He was a very nice, honest person. He never painted in the abstract style. He did Impressionist-type paintings. He liked Bonnard very much.

“One day he went to the Museum of Modern Art with a friend of mine and saw Monet’s Water Lilies. My friend told me that Qian loved it and knelt down on the floor. I saw some of his paintings from the May show on the gallery’s website. They were figurative, with bold colors. In one of them he reinterpreted the Mona Lisa.” The gallery’s website states that Qian has “over twenty-seven” paintings that “spoof” the Mona Lisa.

David Stein, who served time in prison in the United States and France and died in 1999, was not known to create spoofs, but he turned out Chagalls in a hurry.

“So many people wanted Chagalls,” Stein told me. “I remember one day when I operated a gallery out of my apartment on Park Avenue I had an appointment there at one o’clock to deliver three Chagall watercolors that were not yet painted. I got up at six in the morning. The first thing I did was make some tea. I use Lipton tea; it’s the best thing to use when you want to age drawing paper. It gives it a yellowish appearance when you dip cotton in the tea and spread it over the paper.

“Then, while the paper was drying, I made the sketches. I decided on circus scenes. I was working mostly from illustrations from books. One by one, I painted them. I was finished by eleven o’clock. When one was finished, I would put it in front of a sun lamp, which dries the material and cracks it slightly. It’s like cooking.

“I rushed down to a framing place three blocks away. I told them it was urgent, and they framed the three watercolors while I waited. Everything was ready by noon. Then I ran six blocks to a place on Lexington Avenue to make photographs of the watercolors. I rushed back and made certificates of authentication. I know the writing of Chagall and I wrote: ‘I Marc Chagall, certify that this watercolor is an original.’ And I signed Chagall’s name on the back of the photograph. I was finished a few minutes before the dealer arrived. He was satisfied and gave me a check for $10,500.”

Many forgers agree with Stein about the preparations needed to fake art. Eric Hebborn, a forger who was murdered under mysterious circumstances on a street in Rome in 1996, wrote two books and once urged his readers: “Imagine for a moment that you have, in fact, drawn in a manner of van Dyck (1599–1641) and inscribed it ‘Rembrandt.’ This is diabolical. Are there no limits to your skulduggery?” Why? Well, maybe if the forgery is a good one, some expert will think that he spotted a wrong attribution but uncovered a marvelous but unrecorded van Dyck and announce “What an exciting discovery!”

Hebborn was a rogue whose skulduggery knew no limits. He boasted of having produced more than a thousand forgeries (drawings and paintings) of artists such as Bruegel, Pontormo, Corot, Poussin, and Piranesi, among others. (But his former lover announced in 1994 that Hebborn had not made as many works as he claimed to have made.)

Here’s what Hebborn wrote about how to draw like Poussin: “Even Poussin did not learn how to draw like Poussin without years of practice. For just as no one could play the violin in imitation of [a master], unless they had first learned to play it rather well, so it is that no one can draw an imitation of a master draughtsman without being a pretty good draughtsman himself. Long years of practice added to arguably a solid art school background had given me proficiency in the art, and I could at least claim to understand the visual language Poussin used. But now I had to learn his dialect, his accent, his pitch, his almost imperceptible inflections and mannerisms, subtleties that he himself may not have been aware of.”

Hebborn was a friend of Anthony Blunt, a Poussin scholar who served as Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures until 1972, seven years before he was publicly unmasked as a spy for the Soviet Union.

Leo Stevenson, a well-known London copyist, told me that he had met Hebborn. “Some folks are still worried Hebborn drawings are still floating around,” he said.

“I don’t do copies anymore,” Stevenson said. “I am concentrating on my own paintings—mostly landscapes, seascapes, and aviation paintings. I do inventions in the style of everyone from Rembrandt and Hals to Monet. . . . The important thing with forgers is not to understand how artists painted but why they painted the way they did. I always think of it as an actor taking on a role. You have to get into the skin of the person you’re trying to imitate. It’s easier with more recent artists. If you’re going to imitate Rothko, there’s lots of information on him, as well as a play and a film. The further back you go, technically and psychologically, it’s more difficult. The psychological element is just as important as the technical side in creating a fake. Why? If you don’t understand why he painted the way he did, you won’t understand how he did it.

“I’ve done my own inventions of Monet for collectors. I’ve been to all the places he’d been to in France and Italy. I saw the atmosphere of the places and the light. I spent a lot of time in Giverny where he lived. He did a series of haystacks, I would add paintings in the series. They were not copies. They were extra paintings. I’ve probably done about 150 ‘Monets.’”

Stevenson added: “I always try to put a secret in my paintings. They will deliberately fail certain scientific tests. Sometimes I’ll put a joke or a saying on the first layer of paint, and if you X-ray the painting you will see it. I did a Venice Canaletto several years ago. If you X-rayed it, you’d see a submarine coming out of the water.”

Even the British Foreign & Commonwealth Office has commissioned Stevenson. “The British government owns a lot of art,” he said. “Sometimes there might be a polite English fight between one government department and another to have possession of a work. Some years ago, the British Librarywanted works in the Foreign Office—British artists of the 18th and 19th century. The Foreign Office fought tooth and nail to hang onto them and at some point they asked me to do some copies.”

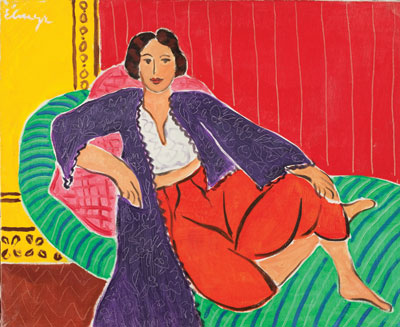

Elmyr de Hory was never accused of making copies. He faked Matisse, Modigliani, Picasso, Derain, and Dufy, and he insisted that David Stein “uttered the worst sort of nonsense” when he claimed that he would go “into the mind and soul of the artist” and became Matisse when he painted Matisse.

“Could you write a story like Hemingway by trying to put yourself into Hemingway’s mind and soul? Could you become Hemingway? No, it’s a terribly vulgar and romantic explanation . . . though I‘m sure the public eats it up. What I did was study—very, very carefully—the man’s work. That’s all there is to it.

De Hory in the style of Matisse: Odalisque (above) is an “original” Elmyr de Hory.

COLLECTION OF MARK FORGY

“With Matisse, for example, I had to be particularly careful. At the beginning . . . I used a very easy, flowing line for a Matisse drawing. Because he had, I thought, a very simple line. And then suddenly later on I realized that his hand was not as secure as mine. Obviously, when he stopped work to glance up at his model, his line stopped, too, with just that tiny little bit of uncertainty. Where I went very securely on, Matisse was hesitant, insecure. I had to correct that; I had to learn to hesitate also. Of course, I never have had much respect for Matisse anyway. . . . He was far and away the easiest artist to fake. (I don’t like that word ‘fake,’ but I’ll use it. I made paintings in the style of a certain artist. I never copied. The only fake thing in my paintings was the signature.) . . . Modigliani, also, was someone I did with great success—not because he’s easy, but because there was such an affinity between us.”

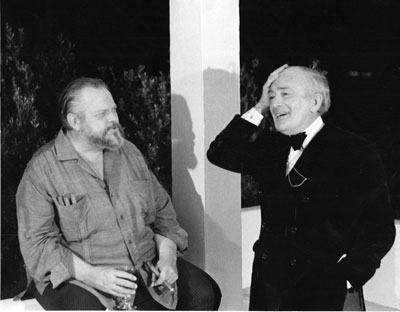

De Hory made these remarks in a biography by Clifford Irving called Fake!. Irving claimed that he had helped Howard Hughes write his autobiography and later admitted that it was a hoax. He went to prison for 17 months.

Elmyr de Hory (right) with Orson Welles, 1972. Welles directed a free-form documentary about de Hory called F for Fake.

RICHARD DREWETT

Two of de Hory’s Modigliani drawings were exhibited many years ago in an exhibition of fakes at theMinneapolis Institute of Artsorganized by Samuel Sachs II, then the museum’s chief curator and now president of the Pollock-Krasner Foundation. The drawings had been bought by a Chicago dealer from de Hory as original Modiglianis. One was sold to a Minneapolis collector and the other to a collector in Chicago. When de Hory was exposed as a forger, the dealer offered the collectors their money back. The Chicago man accepted, but the Minneapolis collector said, “That’s nice, but frankly, I bought the drawing because I liked it and it’s too bad it’s not a Modigliani but I’m going to keep it because we still love it.”

The drawings are now worth about $6,000 each, according to Mark Forgy. “I’m Elmyr’s heir,” Forgy, who lives in New Prague, Minnesota, told me in a telephone interview. “I was his personal assistant for seven years and lived with him on the Spanish island of Ibiza until he died at the age of 70 in 1976.”

De Hory’s real name was Elemér Albert Hoffmann. He was born in Budapest in 1906 and studied art in Budapest, Munich, and Paris. “You might be surprised to know that some of the stories he told me about himself were not actually true,” Forgy said. “He claimed that he came from an aristocratic background. None of that was true. He said his mother was shot by the Russians when they came to Budapest in 1945. His mother actually lived into the 1960s.”

Forgy said that he owns about 300 de Horys. “Many of the works are in the style of Modigliani and the other artists he imitated,” Forgy said. “The vast majority are in his own post-Impressionist style. All the works are signed “Elmyr” or not signed at all.” After de Hory was exposed as a forger in 1967, he signed his works simply “Elmyr” on the front or the back, Forgy said.

Forgy said he sells de Hory drawings at prices ranging from $2,500 to $8,000 and paintings from $6,000 to $8,000. He recently self-published a book about de Hory titled The Forger’s Apprentice. He and Kevin Bowen wrote a play with the same title that was performed in August at the Minnesota Fringe Festival in Minneapolis.

Are there any fake de Horys?

“I see them all the time on online auctions,” Forgy said. “Most often they have the fake signatures of Matisse, Modigliani, Picasso, or Dufy on the front and a fake Elmyr signature on the back. They sell in the $2,000 to $3,000 range but they’re fake fakes. I have the real Elmyrs.”

Milton Esterow is editor and publisher of ARTnews. Additional reporting by Amanda Lynn Granek.

Copyright 2013, ARTnews LLC, 48 West 38th Street, New York, N.Y. 10018. All rights reserved.

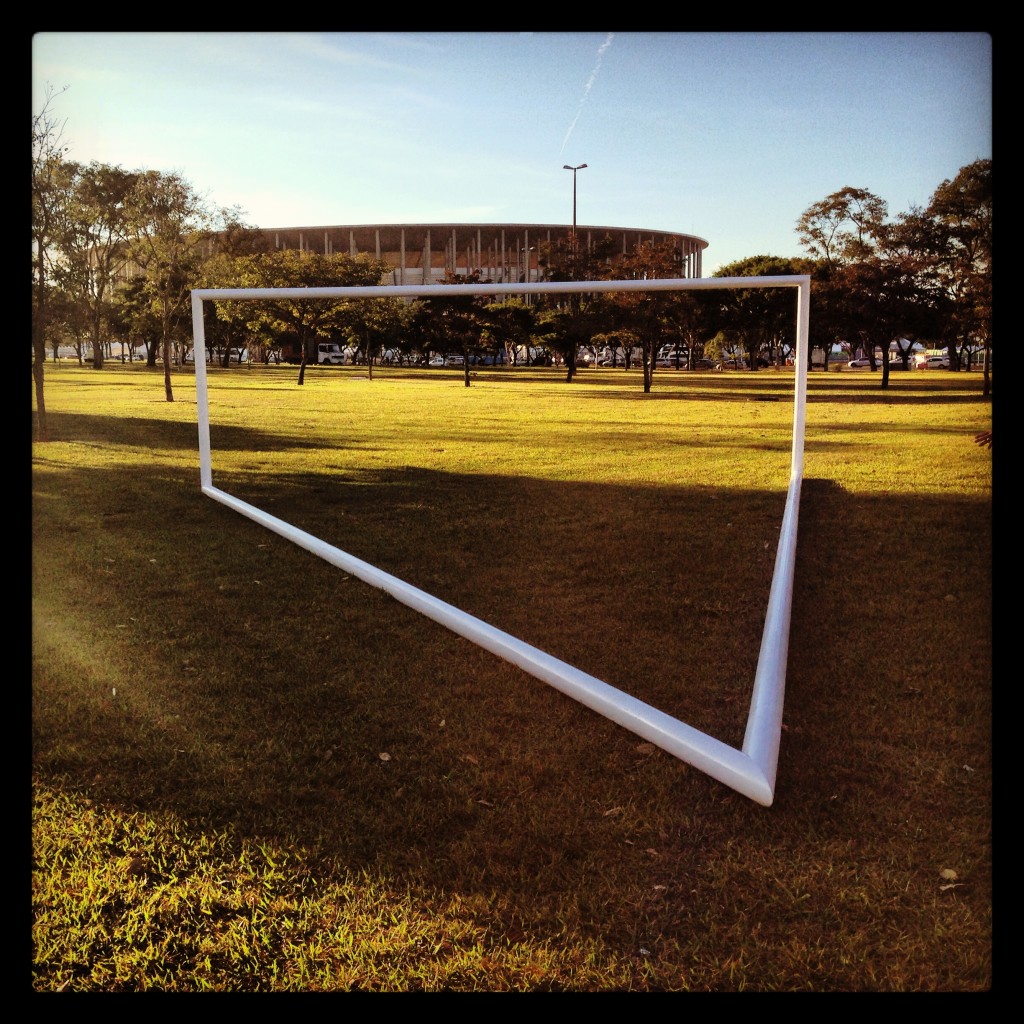

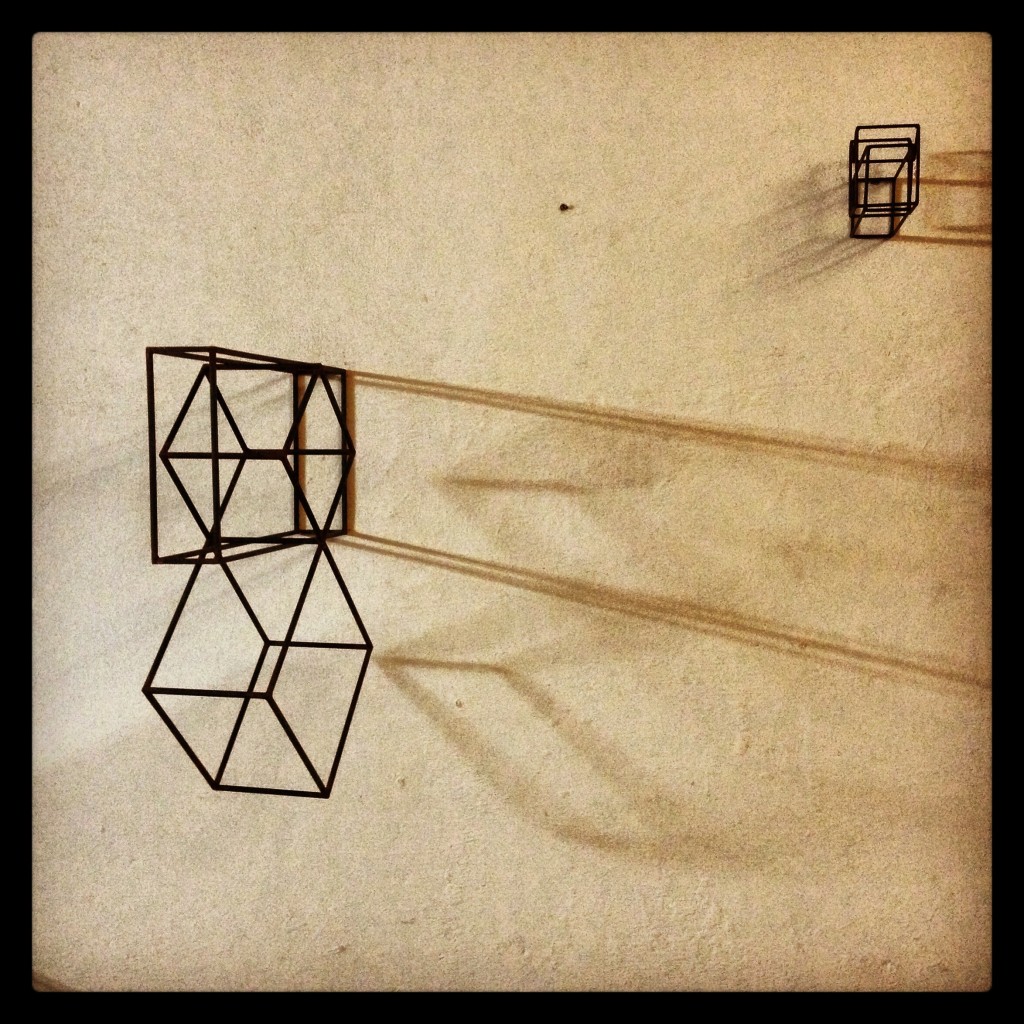

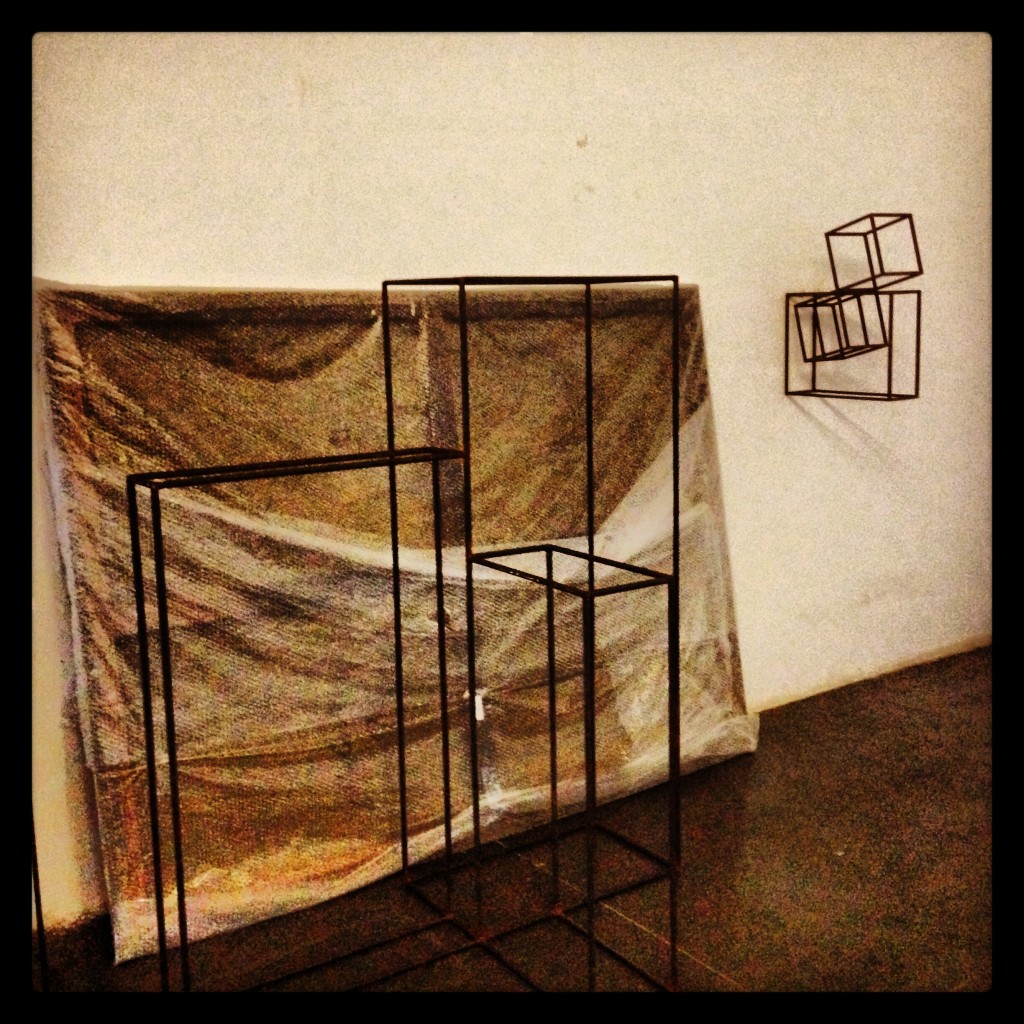

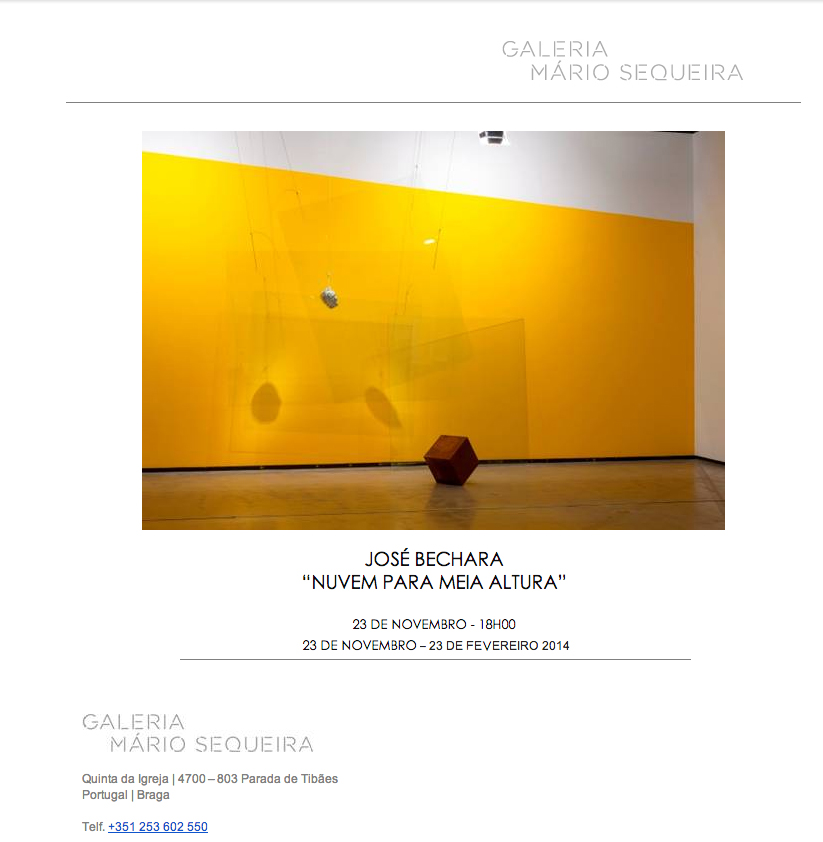

José Bechara @ Galeria Mário Siqueira

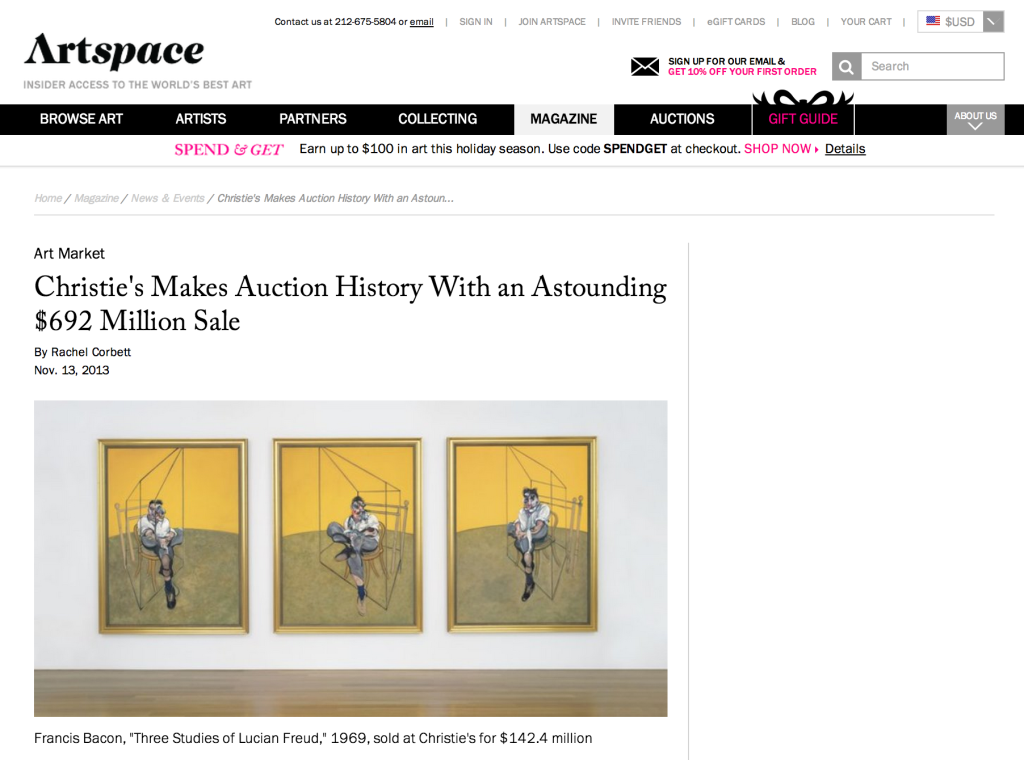

Christie’s Makes Auction History With an Astounding $692 Million Sale – By Rachel Corbett

peguei lá no Artspace.

After last year’s record-breaking $495 million sale atChristie’s, many were left stunned by the contemporary art market’s unwieldy, perhaps even unsustainable, new proportions. But now Christie’s has trounced that record with last night’s historic $692 million contemporary art sale, an almost unbelievable tally that stands as the highest-ever total for an auction house.

Several artworks toppled records throughout the night—most dramatically Francis Bacon’s Three Studies of Lucian Freud, 1969, which sold for $142.4 million to beat out Edvard Munch’s The Scream as the most expensive piece of art ever to be sold at auction. Seven bidders battled it out for the angst-ridden triptych of Bacon’s friend and fellow painter, but Acquavella Galleries, it is thought, ultimately prevailed with a total roughly $60 million higher than the artist’s previous record, set by Russian billionaire Roman Abramovich atSotheby’s in 2008.

Meanwhile, an unnamed telephone buyer set a new record for a living artist with the purchase of Jeff Koons’s gleaming orange Balloon Dog, which went for $58.4 million, edging above its $55 million high estimate. Before bringing the work to auction last night, the Greenwich-based billionaire Peter Brant had been one of just five elite collectors to own one of Koons’s signature steel puppies. Could a Qatari royal be joining the ranks of Francois Pinault, Eli Broad, Dakis Joannou, and Steve A. Cohen? Speculation is already flying.

New artist records were also set last night for Willem de Kooning ($32 million),Christopher Wool, ($26.5 million), Wade Guyton ($2.4 million), Wayne Thiebaud($6.3 million), Lucio Fontana ($20.9 million), Donald Judd ($14.2 million), and four others.

Among the other notable sales, a Cindy Sherman “Centerforlds” photograph of a woman in cinematic peril more than doubled its low estimate to fetch $2 million. One of Warhol‘s gigantic black-and-white Coca-Cola-bottle paintings (there are only four in existence), an iconic—and, if you’re from the midwest, literal—Pop masterpiece from 1992, sold for a stunning $57.3 million, just under its $60 million high estimate; later in the evening, one of his splendid hammer-and-sickle paintings reaped $3.5 million. Further down the Pop lineage, a sexy Roy Lichtenstein Ben-day-dotted nude overshot its estimate to take home $31.5 million, and an Ed Ruscha painting of the American flag brought in $4.2 million.

The series of contemporary sales thus far at Phillips and Christie’s have been a dizzyingly potent remedy to the bleak Impressionist and Modern sales last week, which failed to generate some much-needed enthusiasm in the category. Tomorrow night, Sotheby’s will round out the New York sales with its season-closing finale.

RELATED LINKS:

Art Market: Phillips Kicks Off Auction Week With A Pop-Powered Sale

Homenagem a André Stolarski no Teatro Oficina, dia 25/11 às 20h

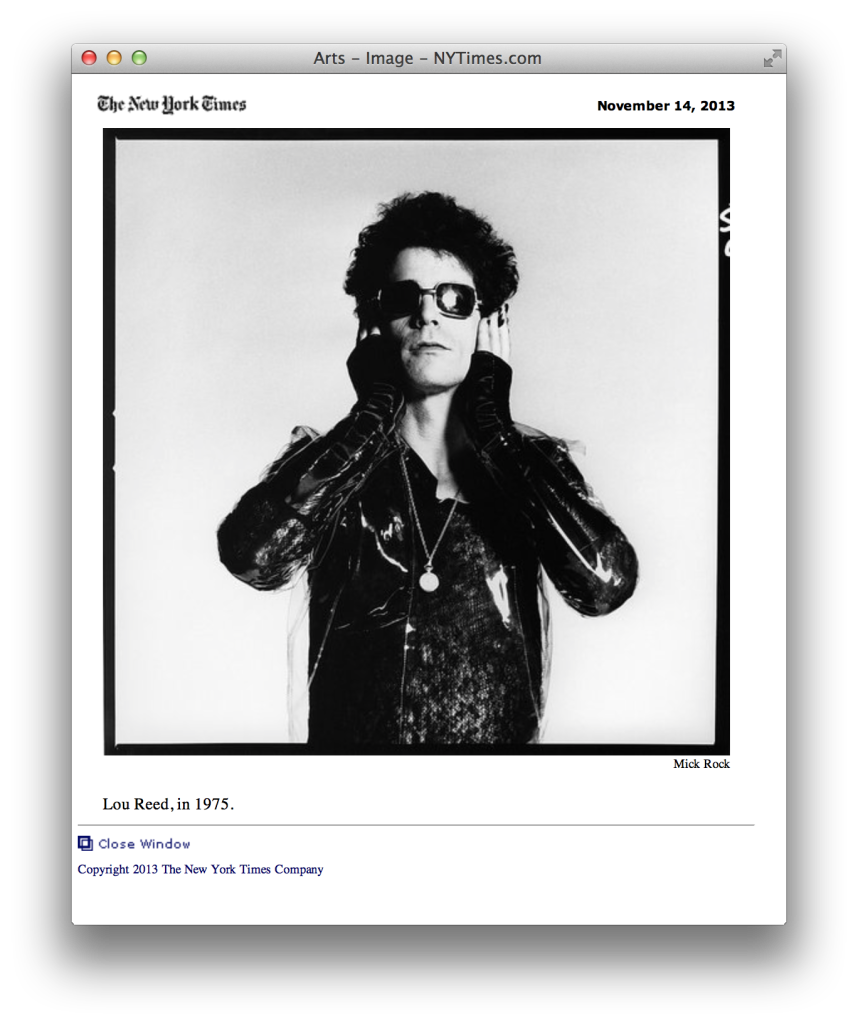

Lou Reed’s New York Was Hell or Heaven By Michiko Kakutani

Lou Reed’s New York was a tough place. It was a place of “dark party bars” and neon lights, a “funny place/Something like a circus or a sewer,” despite the “new buildings/Square, tall and the same” — a place as distinctive as Chandler’s Los Angeles or Baudelaire’s Paris. He wrote about New York with a mix of journalistic observation and deeply felt emotion, a poet’s tenderness and a bad boy’s street cred, creating a soundtrack to the city that resonates decades after Times Square has been hosed down and scrubbed clean, and the Village and SoHo and TriBeCa have been transformed from grungy bohemian haunts into destination stops on luxury real estate search engines.

(A public event, “New York: Lou Reed at Lincoln Center,” is scheduled for Thursday afternoon at the Paul Milstein Pool and Terrace at Lincoln Center, near where Reed and his wife, the musician and performance artist Laurie Anderson, joined Occupy Wall Street protesters some two years ago.)

For some of Mr. Reed’s older fans, his portraits of New York are like old black-and-white snapshots (or the monochrome covers of old New Directions paperbacks), summoning memories of a time when they were young and defiant and searching for some elusive something. For generations of younger fans, too, his gritty view of life on the edge and his primal, uncompromising music remain an inspiration. He was “an early calling card to New York and how to be an artist,” Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth told Rolling Stone magazine. “He was like the Empire State Building to me.”

Mr. Reed was a pioneer on rock’s frontier with the avant-garde, translating lessons he learned at Andy Warhol’s Factory, and the disruptive innovations of the Beat writers — Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs and Hubert Selby Jr. (“Last Exit to Brooklyn”) — to the realm of popular music. He not only embraced their adversarial stance toward society and transgressive subject matter (in songs like “Street Hassle” and “Heroin”) but also developed his own version of their raw, vernacular language, while adding a physical third dimension with guitars and drums. His early songs for the Velvet Underground — delivered in his intimate, conversational sing-speak — still sound so astonishingly inventive and new that it’s hard to remember they were written nearly half a century ago.

If Mr. Reed provided a literary bridge to the Beats (and through them, back to the Modernists, and the French “decadents” Rimbaud and Verlaine, and even Poe, the subject of his 2003 project “The Raven”), he also created a bridge forward to punk and to glam, indie, new wave and noise rock. He would become a formative influence on musicians like Talking Heads, Patti Smith, Roxy Music, R.E.M., the Sex Pistols, Sonic Youth, the Strokes, Pixies, and Antony and the Johnsons. As his friend the artist Clifford Ross observed, “Lou was the great transmitter” — of ideas, language and innovation.

What gave Mr. Reed such a broad artistic wingspan was the extraordinary emotional and sonic range of his work: his access to both the sunlit and darkly shadowed parts of his psyche, his magpie’s love of so many genres of music and his willful determination to continually experiment. His music from album to album (sometimes from track to track) often seemed deliberately to subvert expectations. His 1972 album, “Transformer” — which mixed rough street reportage with playful, trippy musings in classics like “Walk on the Wild Side,” “Perfect Day” and “Satellite of Love” — was followed by his dark, ambitious song cycle “Berlin,” and a few years later by the deliberately difficult “Metal Machine Music” (1975), a howling hour-plus-long barrage of feedback and electronic noise.

“It’s not that he didn’t care what people thought,” his longtime producer and collaborator Hal Willner said last week. “He cared. But it wasn’t going to change what he did.”

Though Mr. Reed was famous for his aggression, for the intensity of songs like “White Light/White Heat” or the snarling perversity of “Sister Ray,” he was equally the master of hauntingly beautiful ballads like the deceptively simple “Pale Blue Eyes” or “Oh! Sweet Nothing,” a moving hymn to the lost and dispossessed. His work tended to move between polarities: between anger and vulnerability, angst and empathy, sarcasm and yearning; between screaming guitar riffs and pretty doo-wop harmonies; between dissonance and melody; between belligerent head-fakes and earnest soul-searching.

At the same time, Mr. Reed found a way to use the dynamic between words and music, pairing, say, lyrical melodies with corrosive tales about violence, suicide and drug use; swirling, ecstatic guitars with minimalist lyrics. In performance, his inflection and delivery added to the contradictions, underscoring both his own chameleon moods and the beauty and pain that make up what he called “the vertigo of life.”

Over the years, Mr. Reed’s work seemed to grow more directly autobiographical. Albums like “The Bells” (1979), “The Blue Mask” (1982) and “Set the Twilight Reeling” (1996) delved into many of the same subjects (the weight of family history, questions of identity, the transience and intractability of time) that had animated the poems and stories of his teacher Delmore Schwartz — whom he regarded as a formative mentor — and that pointed up these very different artists’ emotional affinities.

In a 1987 interview, Mr. Reed talked about seeing his record albums as chapters in one huge, long novel: “They’re all in chronological order,” he said. “You take the whole thing, stack it and listen to it in order, there’s my Great American Novel.” “Pass Thru Fire,” the recent volume of Reed’s collected lyrics — dedicated to “L.A.,” Laurie Anderson — provides another version of that novel, and even without the essential soundtrack, the lyrics possess a remarkable organic coherence, charting a harrowing journey through the bohemian underworlds of New York City, through the ravages of heroin and speed, and emotional terror, fury and aloneness — and toward something like grace.

Whether it’s Candy who hates “the big decisions/That cause endless revisions in my mind” or the lost souls in “All Through the Night” yearning “for a bell to ring” when “the daytime descends in a nighttime of hell,” the people in his songs are all searching for something — a dream, a fix, someone to hold — that might see them through the midnight hour.

In the volume’s final song, written in 2008 and clearly addressed to Ms. Anderson, Reed wrote about finding a balm for the negativity that had once hobbled him — his propensity to think about the past instead of “what could be,” the rain instead of the sun.

The magic ability of love to help us transcend loss and self-doubt is the fulfillment of a wistful hope, sketched decades ago, in one of his early and loveliest songs, “I’ll Be Your Mirror”:

“I’ll be your mirror, reflect what you are

In case you don’t know

I’ll be the wind, the rain, and the sunset

The light on your door

To show that you’re home.”

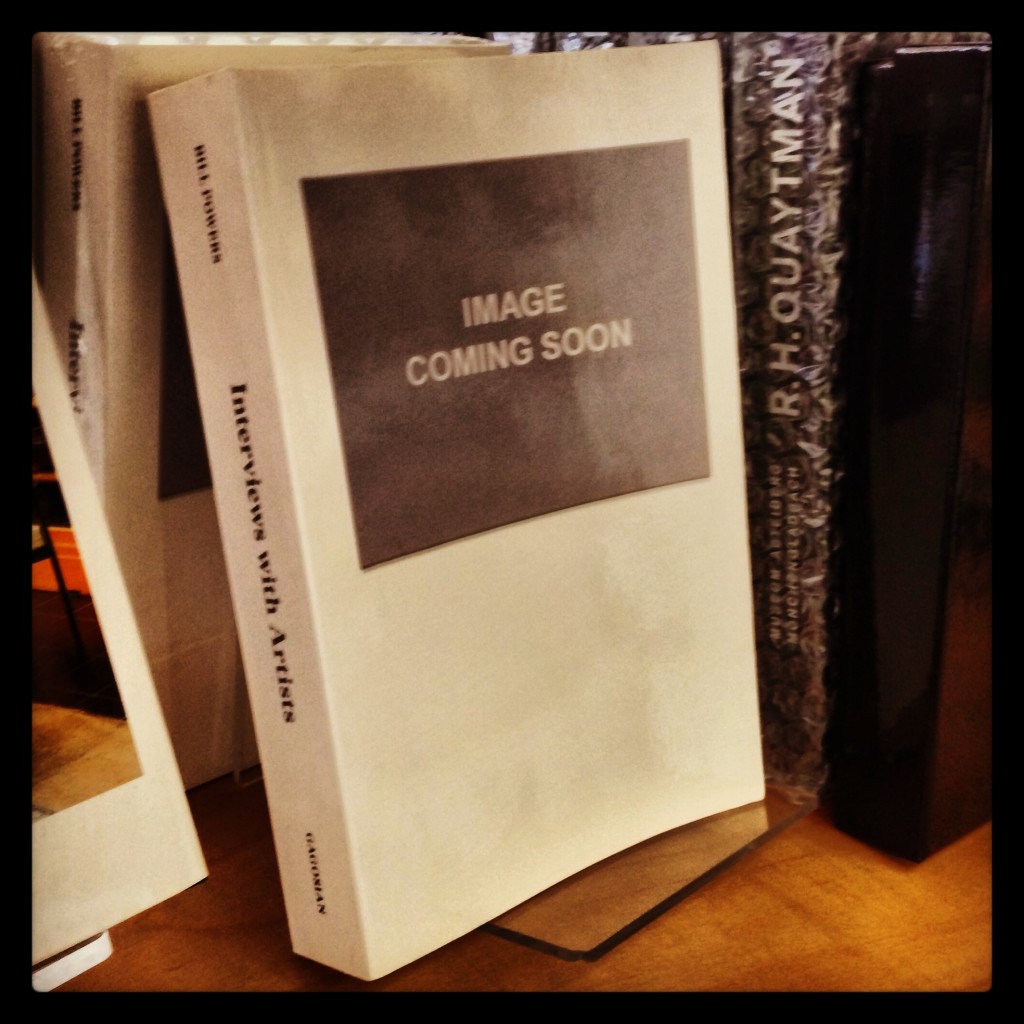

Contemporary Art Brazil

Nas boas livrarias de Ramos e também no site da Thames & Hudson.

Raul Mourão’s involvement with art goes far beyond his own practice, which encompasses sculpture, installation, drawing, video, photography and performance. He constantly seeks new platforms for engaging with audiences in the arts, be it through editing, curating, writing or opening his studio to discussion groups. Born in Rio in 1967, he studied open courses at EAV (Escola de Artes Visuais do Parque Lage) in Rio.

Largely inspired by sports and other events in the public arena, Mourão has pursued two distinct narratives, one closer to fiction and the other more documentary in nature. In Seven Artists (1995) and Artists (2003) he hanged fellow artists with climbing equipment on the wall of exhibition spaces. By employing humour and irony as strategies, these works deal with notions of sculpture, performance and display in turn. The documentation of both happenings was later turned into videos. A similar use of humour and irony can be seen in the series Luladepelúcia (2005), which can be roughly translated as ‘Plush Lula’. Consisting of miniaturised teddy-bear reproductions of Brazil’s popular former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, the piece appeared after a major corruption scandal engulfed his government. Here Mourão was confronting a sentimental image of the president with the corrupted one being propagated by the media of the time. Not surprisingly, his work was interpreted as both critical and adulatory.

The increasing presence of security grilles in Brazil beginning in the 1980s has been the starting point for many of Mourão’s works. In 1988, he began photographing the grids protecting Rio’s air conditioners and trees. In the mid-1990s, he started to reproduce those grates, developing works such as House/Tree/Street (1996), in which he surrounded a tree with a house-shaped iron structure, or Another Thing (2003), a site-specific installation exhibited at the Museu Vale do Rio Doce in Espírito Santo. The latter piece consisted of a series of grid structures with some of which visitors were encouraged to interact, thus experiencing the feeling of being both behind bars and outside of them. Around 2009, having been invited by the theatre company Intrépida Trupe to design some sets, Mourão started his Balances series, a further development of the grid theme. Here the bars are kinetic, allowing viewers to set them in motion, thus creating myriad new presentations while expanding notions of inside and outside.

Isay Weinfeld – A/Z @ Espasso

TIMELINE #8

31st Bienal de São Paulo workshop: call for applications

As part of the activities concerning the 31st Bienal de São Paulo exhibition (September 2nd – December 7th 2014) São Paulo Bienal is hosting a three-week curatorial workshop titled A Tool Box for Cultural Organization.

Leaded by 31th Bienal curatorial team (Charles Esche, Galit Eilat, Pablo Lafuente, Nuria Enguita Mayo and Oren Sagiv), the workshop will give 15 young curators, artists, writers or cultural activators the possibility of engaging in a discussion about organisation and intervention in artistic and cultural contexts, and intends to provide them with key tools for engaging critically in artistic and cultural production today.

Invited speakers include: Ana Longoni, Charles Esche, Ekaterina Degot, Gali Eilat, Ivo Mesquita, Oren Sagiv, Orlando Maneschy, Nuria Enguita Mayo, Pablo Lafuente, Ricardo Basbaum, Sandi Hilal & Alessandro Petti, Suely Rolnik, Vasif Kortun and Walid Raad.

PRATICAL INFORMATION

A Tool Box for Cultural Organization

Workshop in three parts

27-31 January 2014

12-16 May 2014

6-10 October 2014

Monday to Friday, 1pm-8pm

São Paulo, Brazil

Applications

The workshop is free of charge and 15 participants will be selected after an open submission call. The selection will be made on the basis of their past activities and a written presentation articulating the reasons for their interest in the programme. Applicants must speak Portuguese or Spanish + English and be engaged in artistic and cultural production.

Applicants should send CV or Portfolio + Cover Letter (up to 500 words) to

workshopcuratorial@bienal.org.br until 25 November 2013.

Applications will be assessed by the curatorial team, and successful applications will be notified by 16 December 2013.

As a Landmark Auction Opens a New Era, the Dia Art Foundation Pivots Toward New Media Art By Rachel Corbett

Peguei lá no Artspace essa matéria da Rachel Corbett publicada em Nov. 7, 2013.

The Dia Art Foundation is expecting an infusion of about $20 million when it sells off all of the Cy Twomblys in its collection, plus a few John Chamberlains, and its onlyBarnett Newman, at Sotheby’s postwar and contemporary art auctions next week. It’s a big move for an institution whose reputation rests largely on the very 1960s-era Minimalist and Conceptual art with which it’s parting ways. But Dia director Philippe Vergne has said that the museum “cannot be a mausoleum,” and plans to use the proceeds to fund a new acquisition budget.

It remains to be seen what Dia—which famously underwrote some of America’s greatest Land Art works during the 1960s and ’70s—will ultimately do with the money, but the institution has expressed a clear interest in branching out into new media. “It has been very much our mission in the last few years, commissioning new work in performance and sound art,” said Kelly Kivland, a Dia curator with a background in performance art.

Some might have noticed this playing out already. Last month, curators brought the postmodern choreographers Lisa Nelson and Steve Paxton to perform at its soon-to-open Chelsea outpost, and Dia will continue working with the pair during the year to prepare for a return performance next fall. (In 2011, Dia staged a similar year-long dance series with Yvonne Rainer.)

The institution has also increased the performance budget for its annual fund-raising galas, last year commissioning video artist Tony Conrad and, next week, plans to feature a new live work from the electronic-music duo Matmos. Kivland stressed that the event will be more than a party performance—“it’s actually part of a program.”

Drew Daniel, who comprises one half of Matmos along with his partner M.C. Schmidt, agreed that they wanted to do more than just entertain guests at a “swanky party.” And so the Baltimore-based duo traveled to New York in September to begin recording a site-specific project inside the former Alcamomarble factory at 541 W. 22nd Street, which will house the new Dia space.

From inside the empty, echo-y space, Daniel and Schmidt sang and hummed drone-like melodies, whistled on bird and duck calls, dropped plastic tubes, rocks, and metal rods on the floor and threw cell phones against the walls.

“We tried to capture the sound of the room as it responded to different intensities of noise and activity,” said Daniel. The sounds will be remixed, layered, and ultimately recycled back into the same space from which they originated when the pair live mixes the new tracks at Monday’s event.

The event also includes an eight-person chorus comprised of volunteers from the event. The singers will wear headphones and sing back the recorded words they hear, which come from mysterious-sounding transcripts of “the statements of experimental test subjects during the Ganzfeld experiments into telepathy.”

Apart from literally co-opting the framework of the museum, Matmos also sees itself operating, in some ways, within the larger conceptual structure that Dia has helped establish since the 1970s. Thinkers like Sol LeWitt and Lucy Lippardhave been “a huge influence on how M.C. Schmidt and I think about the relationship between sound-as-sound, and the conceptual implications surrounding how we identify what the source of a sound is,” Daniel said. “Our work is neither the concept nor the sounds of our songs but rather the forcefield of tension and relationship between those two related, yet distinct, zones; the work happens when images and words and cultural context acts upon the raw immanent experience of hearing vibrations and they struggle for determination.”

“This project is an extension of something that’s very much been a part of our history,” said Kivland, noting that the organization helped Minimalist composer La Monte Young realize his Dream House in 1979, and acquired Max Neuhaus’s sound installation Times Square in 2002.

“But because we have this increased presence in New York City, we’re really honing in and invigorating and have an earnest dedication to increasing our performance and sound program. It’s always been a part of it, but there’s a recognition that it’s going to be renewed.”

Eduardo Coimbra _ 2 esculturas

A escultura como abrigo

Felipe Scovino

Sempre interessou a Eduardo Coimbra compreender e alargar os sentidos a respeito do que significa paisagem. De uma maneira onírica, o artista fez com que céu e terra se encontrassem em Nuvem (2008) e, portanto, o que era da ordem do ar e da visão pudesse – poeticamente – ser finalmente experienciado também através do toque. Em Asteroides (1999), uma série de recortes de uma paisagem torna aparente um quebra-cabeça que formalmente alude ao astro que dá título à obra. É a concepção de um novo mapeamento sobre o mundo, como se tivéssemos voltado à Pangeia: um mundo uno e indivisível e que, por isso mesmo, só pode habitar o território da ficção.

Contudo, duas outras obras parecem ter um grau de correspondência mais próximo com 2 Esculturas (2013), a obra que está em questão neste breve ensaio, instalada temporariamente na Praça Tiradentes. São elas: Através (2002) e Natureza da Paisagem (2007). Na primeira obra, um projeto ainda não executado, o artista propõe a fabricação de um morro que seria atravessado por manilhas com uma espessura e altura que permitiriam ao público (um adulto com as costas levemente arqueadas seria um parâmetro) percorrer de ponta a ponta aquela natureza artificial. Já Natureza da Paisagem, realizada em 2007 no MAM-RJ e em 2011 no Museu de Arte da Pampulha, consistiu no deslocamento simbólico da paisagem externa – ou melhor, vizinha ao museu – para dentro da instituição. Milhares de vasinhos de grama foram introduzidos no cubo branco, não efetivamente como uma situação de embate com o cubo branco, mas fundamentalmente como uma situação de dobra, no sentido deleuziano do termo, como se nada pudesse separar os dois espaços, já que eles seriam “um espaço de montagem contínua”, constituindo um “dentro” que é a “dobra do fora”. As curvaturas da dobra se entrelaçariam sem conseguirmos distinguir o que estaria fora ou dentro.

E é neste ponto que esse pequeno histórico das obras de Coimbra se conecta a 2 Esculturas. Instaladas no Centro do Rio de Janeiro em um momento em que a cidade passa por um grave processo de gentrificação, especulação imobiliária, aumentos de aluguéis e mobilidade geográfica de seus moradores, é curiosa a forma como a geometria instalativa do artista ressalta o uso de uma escultura como uma casa-abrigo. Discutindo o lugar de uma prática social da arte e o que difere, e ao mesmo tempo aproxima, espaço público e privado (outro tema recorrente na obra do artista), ao ter o seu volume vazado constantemente preenchido por transeuntes da praça, que investem naquela obra como um espaço lúdico, ou moradores de rua, que a utilizam como casa, 2 Esculturas põe em questão um modelo de modernidade que, com sua ideologia globalizante e perversa – visível na redistribuição precária do espaço e dos poderes político e econômico –, transmite sinais de colapso, como temos assistido desde junho deste ano no Brasil com as manifestações populares. A obra 2 Esculturas nos alerta significativamente que os limites entre público e cidadão parecem ter sido borrados. Há o tom lúdico na obra, mas fundamentalmente o posicionamento da arte como uma ação coincidente com a política. Faço referência a outro momento político das artes que formalmente encontra uma ressonância com esta obra. Numa atitude ideológica, e até certo ponto utópica, a Bauhaus desejou contaminar o mundo com arte. A geometria, aliada a um processo de industrialização e dispersão nos meios de consumo, estava contida em produtos que variavam de uma caneta até a construção de uma casa. Guardadas as devidas especificidades e proporções, geometria e política encontram-se novamente em 2 Esculturas.

As novas configurações que um pensamento arquitetônico, como o da escultura em questão, promove na cidade também significam refletir sobre a esfera política da arte. É singular o fato de que as duas esculturas estão situadas ao lado de um dos monumentos mais antigos da cidade e o quanto esse embate entre o novo e o antigo, o eterno e o transitório, o opaco e o translúcido repercute na continuidade da reversão de um espaço que se torna cada mais vez penetrável ou fluido para o público, e envolve uma discussão que passa pelo campo da estética até temas sociais como o acesso livre às áreas públicas de lazer, cidadania e o sentido de pertencimento à cidade.

Em 2 Esculturas, a paisagem funde-se à obra. Todo o entorno é ativado pela escultura pelo simples fato de ela ser uma estrutura que é atravessada pelo olhar. O seu volume é “preenchido” pelo vazio, que nesse caso é o próprio espaço de apropriação e experimentação do público. É ali que a escultura é moldada por ações tão díspares quanto transformar-se num cômodo ou servir como um anteparo para brincadeiras. É o momento em que o espaço social e o político se fundem ao mesmo tempo em que se revela uma das mais significativas contribuições que a obra de Coimbra traz para o repertório da arte.

A estátua equestre de D. Pedro I, instalada na praça em 1862.

Em agosto de 2011, a Praça Tiradentes teve as grades que a cercavam por completo retiradas.

Janaina Tschäpe @ Tierney Gardarin

The Ghost in Between (still), 2013. Two channel video installation. Dimensions variable. 10:11 minutes, with sound. Edition of 4.

Janaina Tschäpe: The Ghost in Between

November 1 – December 14, 2013

Tierney Gardarin Gallery is pleased to present Janaina Tschäpe: The Ghost in Between on view November 1st through December 14th, 2013. This will be the artist’s first exhibition at the gallery and she will be present at the opening reception from 6:00 pm till 8:00 pm on Friday, November 1st.

Tschäpe’s oeuvre, encompassing a variety of media, is united by recurring themes. Bio-evolutionary life cycles conflate with mythological, transmographying creatures, and water spirit myths from Northern Europe meld with those from East Africa and South America. Empirical biological phenomena and the seemingly fantastical reveal themselves as a recurring cast of characters in her paintings, drawings, photographs and films. In Tschäpe’s universe, the real and the ethereal blend, the shamans become the biologists, the scientists are revealed as mystics, and the profane atomizes into the sacred.

Tschäpe’s recent travels to the Amazon have inspired a new film, deeply rooted in German Romanticism and Brazilian fairy tales. The piece evokes a form of magic realism indicative of the artist’s complex geographical, cultural, spiritual and intellectual heritage. Both romantic and expressionist in sentiment, The Ghost in Between features sweeping cinematic vistas and profoundly intimate moments, which combine to form an ambiguous narrative. Floating down Rio Negro, the camera captures mirrored reflections all across the horizon; this is the point where ghosts lie. Tschäpe’s combination of image and allegory results in a fantastical landscape reminiscent of early Surrealist tableaux, rendering visible the liminal spaces between the cognitive world and dream states.

For over a decade, in addition to a critically acclaimed body of painting, drawing and sculpture, Tschäpe has deftly used film and video to extend her work from the limits of canvas and paper. Tschäpe, currently lives and works in Brooklyn, NY, and Bocaina, Brazil. Recent solo exhibitions of Tschäpe’s work have been presented at the Kasama Nichido Museum of Art, Nichido; Roger Ballen Center for Photography, Johannesburg; Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin; Contemporary Art Museum, Saint Louis; and Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid. Her paintings, videos, photography, prints and drawings are included in numerous public collections, including: the Centre Pompidou, Paris; the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC; the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; the Reina Sofia, Madrid; the Museu de Arte Moderna, Rio de Janeiro; Harvard Art Museum, Boston; and the Progressive Art Collection. MOCA Tucson will host a solo exhibition of her video and film work in February 2014.

Conversa Tranquila na Praia da Paciência

MAREPE @ ANTON KERN GALLERY

Marepe

October 25 – December 14, 2013

For his third solo show at Anton Kern Gallery, Brazilian artist Marepe presents a group of seven sculptures made of common objects and put together with great formal rigor and poetic potential. These works achieve a complex layering of references and meanings addressing the linkage between the individual and society.

Marepe’s sculptures are made from everyday materials such as plastic buckets and tables, ironing boards, brooms, bicycles, wheelbarrows, and chipboard. Some titles, such as Embutido Sanfona (embedded accordion), are inspired by popular music, others are factual and descriptive, such as Empilhamento (stacking). The work allows for a direct reading, and perhaps more importantly, leads toward a sensory experience; an intimacy of touch and interaction, comparable to the deeply emotional experience and immediacy of listening to music.

Duchamp and Neoconcretismo may be part of Marepe’s inspiration, but it is the artist’s deep concern for the social and for human interaction that drives his art. He combines quotidian objects and materials to form disarmingly simple monuments, some suggesting abstract forms, others depicting figures engaged in dance-like interaction, and in some cases allowing cut-out chipboard to assist in creating specific figures.

Many of Marepe’s titles refer to Brazilian music or lyrics. Embutido Sanfona for example, can be translated as “built-in concertina,” the slightly smaller version of the accordion which is the lead instrument in Forró, a thrilling and infectious folk-pop music from the North-East of Brazil, the region where Marepe grew up and still lives and works. “Embutido Sanfona” also refers to Marepe’s previous wooden models for rooms and trucks and his interest in communal and shared spaces. It is simultaneously a minimalist kinetic sculpture, a model for multi-purpose housing, and a musical celebration.

Marepe’s work speaks, or rather sings of everyday life and love, celebrating and elevating the specific materials and origins of the work to the universal. The ordinary shines in its simple beauty declaring its liberating and transformative power.

Born Marcos Reis Peixoto 1970 in San Antonio de Jesus, Bahia, Brazil, Marepe lives and works in Salvador de Bahia, Brazil. The artist has participated in various group exhibitions including The Living Years, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis (2012); Gigantes por su propia naturaleza, IVAM Instituto Valenciano de Arte Moderna, Valencia, Spain (2011); NeoHooDoo: Art for a Forgotten Faith, The Menil Collection, Houston; PS1, Long Island City; Miami Art Museum, Miami (2008/09); An Unruly History of the Readymade, Jumex Collection, México; When Lives Become Form: Contemporary Brazilian Art: 1960-Present, Museum of Contemporary Art of Tokyo (both 2008); Alien Nation, ICA, London; 27th Bienal de São Paulo; 15th Biennale of Sydney, Sydney (all 2006); Tropicália: A Revolution in Brazilian Culture, Barbican Art Gallery, London; The Bronx Museum of the Arts, New York; Museu de Art Moderna, Rio de Janeiro, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago (2005/06); How Latitudes Becomes Forms: Art in a Global Age, Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston; Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy; the Istanbul Biennial (all 2004). Recent solo exhibitions include Veja meu Bem, Tate Modern, London; Espelho, Museu de Arte Moderna, São Paulo (both 2007), and Vermelho Amarelo Verde Azul, Centre Pompidou, Paris (2005);

The exhibition opens on Friday, October 25 and will run through Saturday, December 14, 2013. The gallery is open Tuesday – Saturday,

10am-6pm. For further information and images, please contact the gallery at (t) 212.367.9663, or email: nahna@antonkerngallery.com.

lá no site http://www.antonkerngallery.com

dia Drumond

Hélio Oiticica in New York City

“Hélio Oiticica in New York City: Babylonests, Cosmococas, and other Projects at the Threshold of Art, Cinema and Architecture”

November 1, 12:30–6pm, Columbia University, 612 Schermerhorn Bldg.

Speakers:

Paula Braga, Federal University of ABC, Sao Paulo

Max Hinderer, Independent scholar

Sabeth Buchmann, Academy of Fine Arts Vienna

Juan Suarez, University of Murcia

Ricardo Basbaum, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, and University of Chicago

Carlos Basualdo, Philadelphia Museum of Art

This one-day symposium brings together an international array of scholars, artists and curators to focus on the various projects the Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica designed during his nearly eight-year stay in New York City (1971–78). The aim of the event is to foster debate on Oiticica’s artistic production, as well as on the relation between the latter and the 1970s New York art world. Admission is free to the public; advance registration is not required.

The event is co-sponsored by Columbia University’s Department of Art History and Archaeology and the Institute for Studies on Latin American Art. The proceedings will be introduced and moderated by Alexander Alberro, Virginia Bloedel Wright Professor of Art History at Barnard College and Columbia University.

Jovana Stokic and Rodrigo Braga

Wednesday October 23st, 2013,

6.30pm. – Free and open to the public

Residency Unlimited

360 Court Street (green door),

Brooklyn, NY 11231

Together with Rodrigo Braga (Brazil), the art historian and critic Jovana Stokic will examine a selection of the artist’s photographs and videos that speak about presence that follows performance. Braga’s works are exclusively performed for the camera, in undisclosed locations and without an audience. As a result of this process, images, therefore allow the viewer to become the witness. For tonight’s event, Rodrigo will present early works in conjunction with his current investigations undertaken in specific areas of New York that have inspired him to inter-react.

Rodrigo Braga (b. Manaus 1976) is a Brazilian artist who currently lives and works in Rio de Janeiro and who earned his graduate degree in Visual Arts at the Federal University of Pernambuco (2002). Braga’s performative practice reveals itself through photography that deals with his relationship with landscape and animals. In his latest series of work, shown at last year’s 30th Bienal de São Paulo (2012), Braga addresses the conflict between man and nature, human and animal

Jovana Stokic is a Belgrade-born, New York-based art historian and curator, who holds a PhD from the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Her dissertation, “The Body Beautiful: Feminine Self-Representations 1970–2007,” analyzes works of several women artists—Marina Abramovic, Martha Rosler, Joan Jonas—since the 1970s, particularly focusing on the notions of self-representation and beauty. She has curated several thematic exhibitions and performance events in the United States, Italy, Spain, and Serbia. Her essay, “The Art of Marina Abramovic: Leaving the Balkans, Entering the Other Side” appeared in the catalogue for The Artist Is Present (2010) at the Museum of Modern Art. Stokic was a fellow at the New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York; a researcher at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; the curator of the Kimmel Center Galleries, New York University; and the performance curator at Location One, New York. She has taught art history at New York University, Fashion Institute of Technology and is on the faculty of the MFA Art Practice at the School of Visual Arts, New York. Stokic is deputy chair, MA Curatorial Practice at SVA.

This event is supported in part by the Sao Paolo art fair and Instiuto De Cultura Contamporanea, Sao Paolo.

Tatiana Blass @ Johannes Vogt Gallery

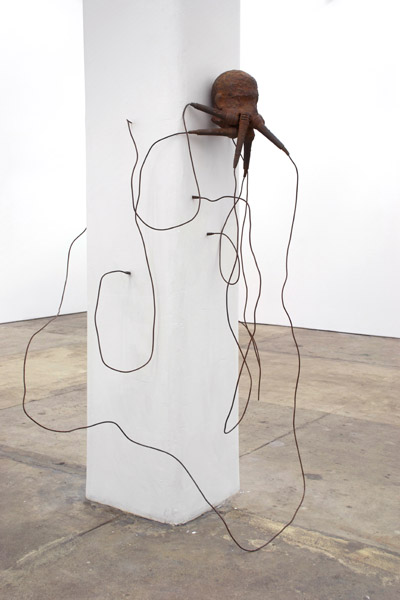

Johannes Vogt Gallery is pleased to announce the gallery’s first solo show with Brazilian artist Tatiana Blass. For her debut in New York, Blass will present a recent body of work centering around the scenario of the interview. The exhibition is composed of two iron sculptures, a suite of oil paintings, and a video work featuring theatrical performance.

As part of the artist’s practice, Blass composes figurative sculptures out of microcrystalline wax that become fluid over the duration of their exhibition. Antagonized by spotlights and heating elements, the sculptures slowly deform and are overtaken by entropy. In the recent works on display, Blass takes up the theme of the interview, composing paintings and sculptures in which subject, audience, and medium break down into one another. Approximating the process of the melting wax, these figures become trapped in between fixed states. As the figures soften and blur, they lose their definite forms, and the line between subjects becomes obscured.

In the paintings and sculptures, Blass engages the dialectics between the subject and the recording apparatus. Instruments of modern technology present anything but a clear medium: human figures and recording instruments appear sucked into one another, collapsing into single forms. In the series of paintings, figures are seen merging into their surroundings, out of which the ominous, near incomprehensible motif of the camera emerges.

This strain is amplified in the video Hard Water, where communication becomes subject to the whims of language, to linguistic play. Two actors engage in an absurd conversation of misunderstanding, during which they become progressively entangled in the numerous threads that bind their clothing to the surrounding walls of the stage. The physical stage records the labors and actions of the two women, visually representing the linguistic entanglement that only worsens as they fight to regain clarity.

Tatiana Blass was born in Sao Paulo, Brazil, in 1979. Her work spans sculpture, painting, video and installation. She has been featured in the 2010 Sao Paulo Bienal with a performance based piece called “Piano Surdo.” She was nominated for the famous PIPA Prize in both 2010 and 2011. She succeeded to win the prize in 2011 with her piece “Blinding Light – Seated” that was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro. This year Blass was given her first US solo show at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Denver. Her works are part of collections such as CIFO, Miami and the museums of modern art in Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo. She is currently featured with a profile in the September issue of Modern Painters and was shortlisted as one of Art+Auction’s “50 most collectible artists under 50.”

lá no site Johannes Vogt Gallery

Balthus: The Last Studies > Gagosian

From time to time, amidst all the trials and errors, it happens: I recognize what I was looking for. All of a sudden the vision that pre-existed incarnates itself, more or less intuitively and more or less precisely. The dream and the reality are superimposed and made one.

—Balthus

“Balthus: The Last Studies” presents for the very first time selections from an extensive but little-known body of preparatory photographic work by the painter, giving fresh insight into the working processes that he adopted late in life. This intimate exhibition also brings to light key continuities and correspondences between images throughout Balthus’s oeuvre, providing a resonant counterpoint to “Balthus: Cats and Girls: Paintings and Provocations,” the thematic survey of early paintings at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York that opens to the public on September 25.

Balthus is commonly known as the reclusive painter of charged and disquieting narrative scenes, whose inspirative sources and embrace of exquisitely rigorous technique reach back to the early Renaissance, though with a subversive modern twist. In the last decade of his life, when physical frailty made it all but impossible for him to draw, he discovered the Polaroid camera—a surprising turn for one who had remained so defiantly aloof from many of the radical innovations of his own time. With it he began making extensive instant preparatory “sketches” for his paintings, which were often many years in the making.

During this time, his artistic energies and attention were reserved largely for his last model, a girl named Anna who posed for him every Wednesday for eight years in the same room, with the same curtain, the same chaise longue, the same window in changing light conditions, the same bucolic mountain scenery looming beyond. What these compelling, jewel-like photographic images reveal—from the dramatic affect of classical gesture to the seeming nonchalance of studied repose—is the extraordinary level of nuance and inventiveness that Balthus was able to evince repeatedly from a simple scene and an approximate photographic method.

In some instances, spontaneous interaction is captured in a single shot; in the first image of the exhibition, Anna presents herself to Balthus’s lens for the first time, a guileless child already possessed of La Gioconda’s mysterious smile. In others, sequences of images reveal fleeting passages of barely perceptible evolution while Balthus intently searches the situation before him to meticulously define each element. And thus Anna is transformed into the stuff of allegory. Each of the 155 Polaroids presented here, which span the years of collaboration between the artist and his last model, is a record of a masterly command of subject and circumstance and of formal obsession pursued to the end.

The exhibition is accompanied by a magnificent two-volume book in a limited release of 1,000 copies, in which the entire corpus of Polaroids is reproduced. It is edited by Nicolas Pages and Benoit Peverelli and published by Steidl.

Balthus (Balthasar Klossowski de Rola) was born in Paris in 1908 and died in Rossinière, Switzerland in 2001. At the age of 13, he published Mitsou, a book of 40 ink drawings with a text by Rainer Maria Rilke, a close family friend. A self-taught artist, he held his first exhibition at Galerie Pierre, Paris in 1934. Following the ensuing scandal, he showed with Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York from 1938–77, although he never visited the U.S. His paintings and drawings are in the collections of key museum and private collections worldwide.

In 1961, Balthus became director of the French Academy in Rome. Over the next 16 years he restored the interior of the Villa Medici and its gardens to their former elegance. During his lifetime, he was also a noted stage designer for Shakespeare’s As You Like It, Shelley’s Cenci (as adapted by Antonin Artaud), Camus’s État de Siège and Mozart’s Così Fan Tutte.

Balthus’s first major museum exhibition was at The Museum of Modern Art in 1956. Other museum exhibitions of note include Musée des Arts Decoratifs, Paris (1966); Tate Gallery, London (1968); La Biennale di Venezia (1980); The Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago (1980); Musée cantonal des beaux-arts de Lausanne (1993); Musée national d’art moderne de la ville de Paris (1984, traveled to Metropolitan Museum, Kyoto); The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (1984); and Palazzo Grassi, Venice (2001). “Balthus: Cats and Girls: Paintings and Provocations”, opening at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York on September 25, will be the first U.S. museum survey of the artist’s work in 30 years.

For further information please contact the gallery at newyork@gagosian.com or at +1.212.744.2313. All images are subject to copyright. Gallery approval must be granted prior to reproduction.

Press Enquiries

Blue Medium, Inc.

T. +1.212.675.1800

www.bluemedium.com

Contact: Deirdre Maher

E. deirdre@bluemedium.com

GP/NY #3

Mais uma colaboração antiga do Gustavo Prado que coloco agora no ar apesar da exposição do Nick Cave não estar mais em cartaz na galeria Mary Boone (10/9 a 22/10 de 2011…). Para ver todas as colunas do Gustavo basta clicar GP/NY na aba das categorias aí ao lado.

Seres repletos

A entrada da galeria Mary Boone no Chelsea é bastante discreta, não há nenhum logo extravagante na fachada, apenas uma porta misteriosa que dá para uma pequena recepção, no fundo da qual, como sempre, uma bela moça, sentada de trás de uma grande mesa com cabelo bem cortado, sorri e espia. No canto mais distante da entrada há uma passagem. Olhando por sua abertura, para a luz que por ela escapa, não há nada que possa te preparar para o que está adiante.

Do outro lado, seres coloridos aguardam, estacionados no centro de uma grande sala. Sua presença e o choque causado pelos objetos e materiais que forjam sua forma e sua pele deixam uma forte impressão, mesmo naqueles já acostumados a todo tipo de estátuas, roupas, corpos, e estranhos tipos de ornamentos que uma cidade tão diversa e pluralista quanto Nova York pode apresentar.

Olhando para sua superfície, pode-se notar que estes corpos são construídos com o acúmulo de estranhos objets trouvé, como pássaros entalhados, corujas de porcelana, bichos de pelúcia, palhaços de brinquedo – com suas cambalhotas mecânicas, bonecas vodoo, globos escolares, peões de corda, tapeçarias mexicanas, tapetes de banheiros com super-heróis e personagens de desenho animado estampados, cata-ventos, cornetas e pirulitos, bandeirolas, sombreiros, macacos de plástico, bules e xícaras, rodas de carroça e lantejoulas, botões, purpurina, flores artificiais etc. E uma explosão de detalhes e cores que formam uma estranha procissão, um desfile fantasmagórico e fantástico paralisado à espera dos nossos olhos; uma junção obsessiva do infantil com o ritualístico, capaz de causar vertigem e assombro.

Sua identidade parece ser dada pelo sentido ou memória do uso passado de todos esses objetos e pelas milhares de associações disparadas com a sua justaposição. Para além de uma apreciação do seu valor escultórico intrínseco, fica a impressão de que eles transmitem uma crítica subliminar. Afinal, quem mais gostaria de ser definido pelos aparelhos e roupas que carrega? Seu exagero parece criar uma caricatura, como uma carapuça que serve.

Outro aspecto desses trabalhos pode ser mais facilmente notado ao tomarmos conhecimento das relações do artista com a dança, ou se tivermos a sorte de testemunhar um dos momentos em que passam de esculturas a figurinos, para tomar parte numa de suas performances. Cave escreveu coreografias específicas para explorar como alguns deles, cobertos com pelos coloridos, criam efeitos impressionantes ao moverem-se, ou para que produzam sons com seu chacoalhar. Eis a razão para que os trajes/esculturas recebam o nome de “Soundsuit”.

Algumas das figuras mais interessantes desta exposição são feitas de centenas de peças de madeira, reunidas para criar uma topografia rústica e orgânica, como uma armadura natural. Elas têm, no lugar de seus rostos, grandes cestos, criando aberturas que parecem reforçar a impressão de que se tratam de criaturas sem alma. Elas trazem a estranha sensação de que o mundo e nós, quando dela nos aproximamos, podemos ser tragados e despencar para dentro do seu vazio. Elas nos lembram também o exército chinês de terracota, como se estivessem à espera de alguma coisa que fosse reanimá-los e trazê-los de volta à vida.

Ao sairmos da exposição, ganhamos a rua com a sensação de que vimos contradita uma das ideias mais antigas da metafísica, ideia essa desenvolvida por Aristóteles, que anuncia que todo ser tem uma essência responsável por realizar o que fundamentalmente é, e que deve retê-la por necessidade, pois, sem ela, perderia sua identidade. A essa essência ele opõe a noção de acidente, ou as propriedades contingentes de um dado objeto sem as quais ele ainda poderia manter sua identidade. A natureza ambígua das esculturas/trajes, seres/personagens que deixamos pra trás na galeria não parece respeitar essa distinção, pois sua identidade é determinada pelos acidentes que sobre ela se acumulam para constituí-la. Elas se apresentam, enfim, como a intrincada narrativa da sua formação.

Aristóteles que nos perdoe, mas com Cave ficamos muito mais próximos das ideias do poeta francês Paul Valéry, que nos disse para não buscarmos muito além, pois o que há de mais profundo é a pele. É dela que extraímos aqui a experiência destas obras, que refletem muito bem a nós mesmos e a nossa época com a riqueza e a complexidade de sua superficialidade.

aqui o site da galeria com o press release da exposição: http://maryboonegallery.com/exhibitions/2011-2012/Nick-Cave/index.html

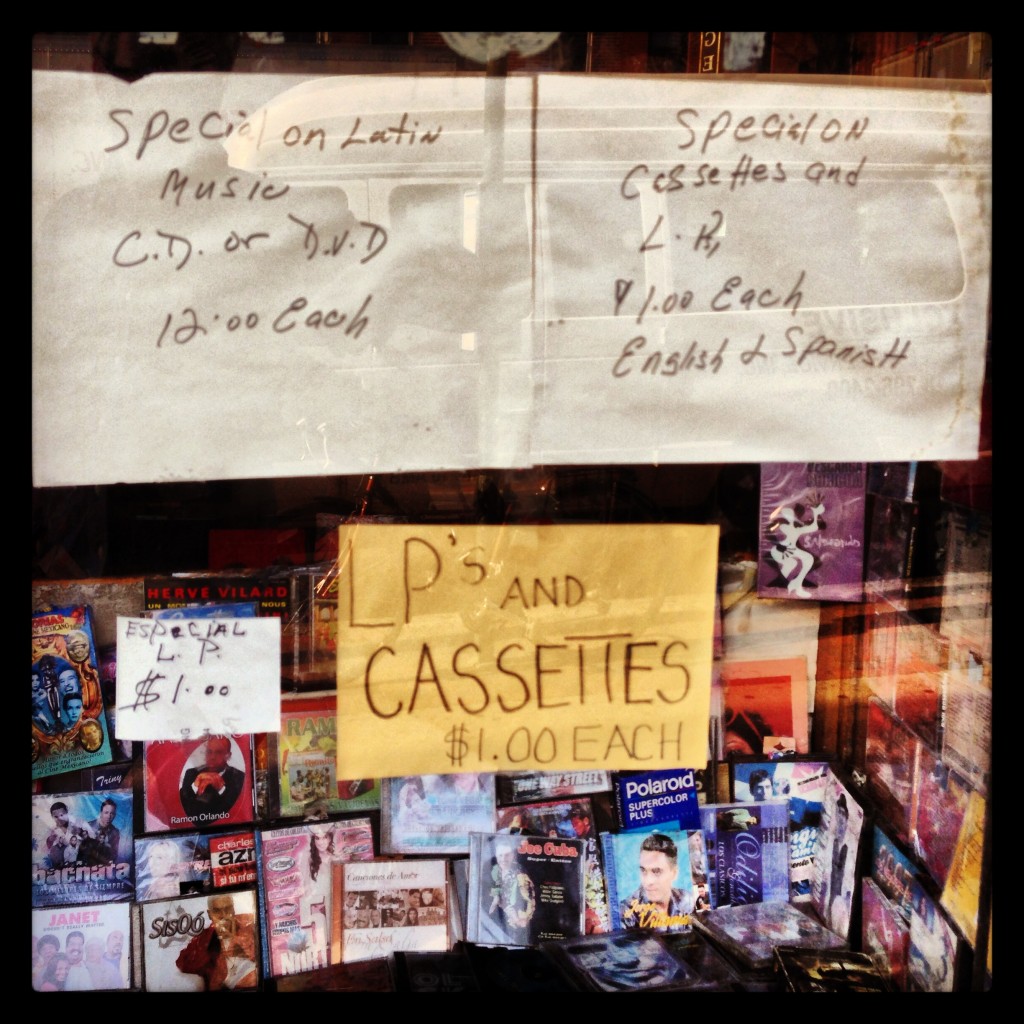

sarahcrown presents #DOCDOTMOV Marcos Kuzka / Raul Mourão

Marcos Kuzka / Raul Mourão

opening Friday October 11, 6-9 pm

Bikinis Salon, 56 Avenue C (btw 4th and 5th)

New York

#DocDotMov investigates contemporary art practice in times of new media, digitalization, and social networking, showcasing the (moving) image and mirroring an ever changing social environment.

#DocDotMov means documentation, archiving, and movement at the same time. Through photography, sculpture, and painting (.Doc) and kinetic installations, video, and light projections (.Mov) the spectator is made to rethink his/her position, emotions, and social values within the expanded field of visual and digital communication.

sarahcrown focuses this time on contemporary Brazilian art and introduces existing and new artworks by Raul Mourão, an unedited Instagram art project, and a video piece by sound designer Marcos Kuzka, conceived expressly for this exhibition.

#DocDotMov introduces a new idea for conceiving art thanks to, and based on, contemporary/social media in order to enjoy and share visual information.

Opening Friday Oct 11, 6-9 pm I Afterparty @Nublu 9 pm – open

Show: Oct 11-18, 6-9 pm I Supported by Xingu beer

GP/NY #2

Gustavo Prado começou a colaborar com o b®og quando eu estava fazendo a mudança do Blogspot para WordPress. A mudança demorou 6 meses e o b®og ficou fora de ação. Nesse periodo ele me mandou um monte de posts que não foram ao ar. Agora resolvi subir tudo ao mesmo tempo apesar das exposições comentadas não estarem mais em cartaz. Uma pena termos perdido o calor da hora mas espero que vocês apreciem os textos do nosso correspondente no Brooklyn. Segue o texto sobre a exposição de Cindy Sherman no MoMA. Já já coloco mais e mais. Para ver todas as colunas do Gustavo basta clicar GP/NY na aba das categorias aí ao lado.

A retrospectiva de Cindy Sherman no MoMA

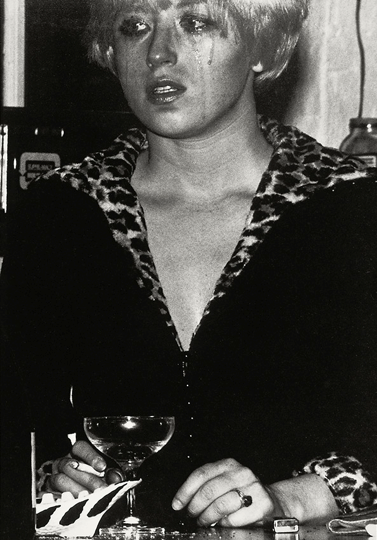

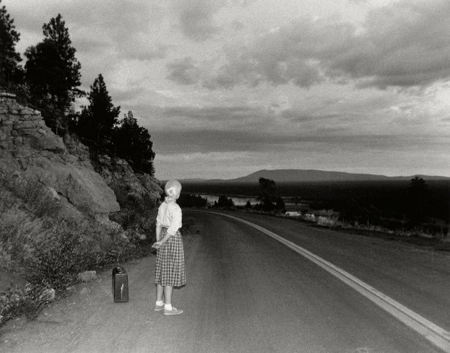

Poucos são os artistas de quem podemos dizer que transformaram ou influenciaram de forma tão decisiva o debate sobre arte contemporânea quanto Cindy Sherman. Ela é ao mesmo tempo causa e efeito da preponderância de Nova York sobre o mundo da arte. Se a relação entre Eduard Manet e Paris constitui uma das principais razões para o nascimento da modernidade, talvez um dia também seja possível compreender como a pós-modernidade tem tanto Nova York quanto Cindy Sherman como grandes simbolos. Seu trabalho é herdeiro direto de alguns dos temas que foram formulados nos anos setenta, mas que devem sua internacionalização e predominância à geração de Sherman. São alguns dos mais notáveis: a apropriação, utilizada em seu trabalho como uma lente de aumento capaz de observar nossa Cultura e os papéis que nela foram “deixados” para as mulheres; o uso do corpo como importante suporte para arte no questionamento de estereótipos e fronteiras entre diferentes meios; o privilégio do conteúdo sobre o meio; o engrandecimento do papel do artista, que se torna tanto sujeito quanto objeto, num esforço muito mais complexo que o mero autorretrato; a exploração e teste da ideia de uma identidade unívoca e coerente, o interesse pela fotografia, a submissão de sua linguagem ao uso como ferramenta e registro de uma performance; e a história da arte como um campo a ser continuamente reinterpretado e re-significado por obras que fazem menção ao cânone. Com tantos temas decisivos relacionados à sua obra, ela é parte de uma grande virada histórica. Enquanto na década de oitenta o neo-expressionismo tornava homens-pintores famosos e ricos, trabalhos muito mais significativos criaram o que foi provavelmente um dos mais importantes momentos para mulheres na história da arte: quando artistas como Diane Arbus, Adrian Piper e Hanna Wilke passaram o bastão para Sherman e suas contemporâneas como Sherrie Levine, Barbara Kruger, Nan Goldin, Jenny Holzer, Kiki Smith, entre outras, que ao extrapolar a então chamada “arte feminista,” colocaram a nova geração de mulheres artistas na posição de grandes protagonistas da produção contemporânea.

Untitled Film Still #27. 1979