CARLITO + ROSSANO no MAC USP

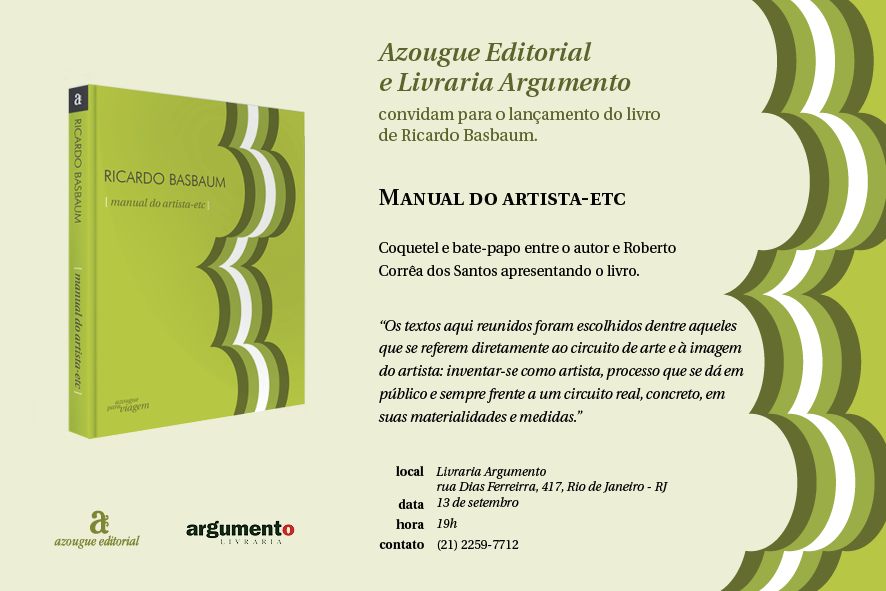

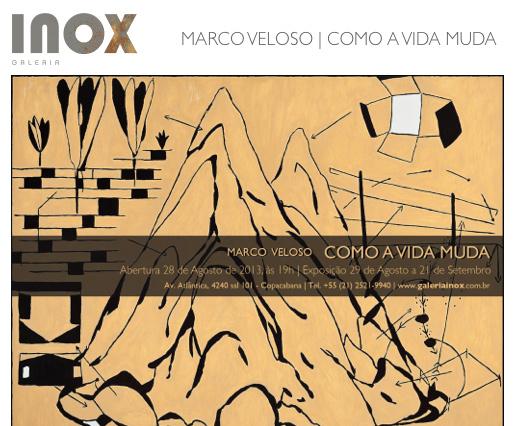

Marco Veloso na INOX

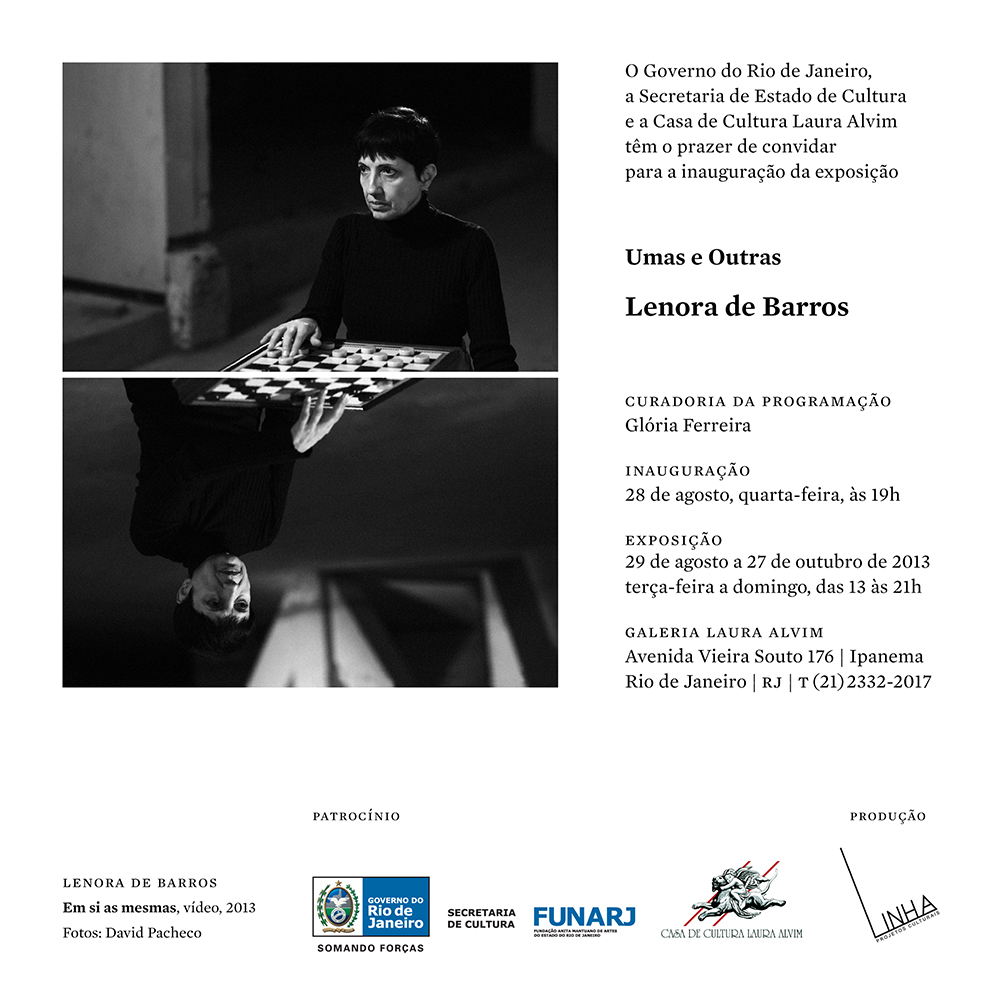

Lenora de Barros na Laura Alvim

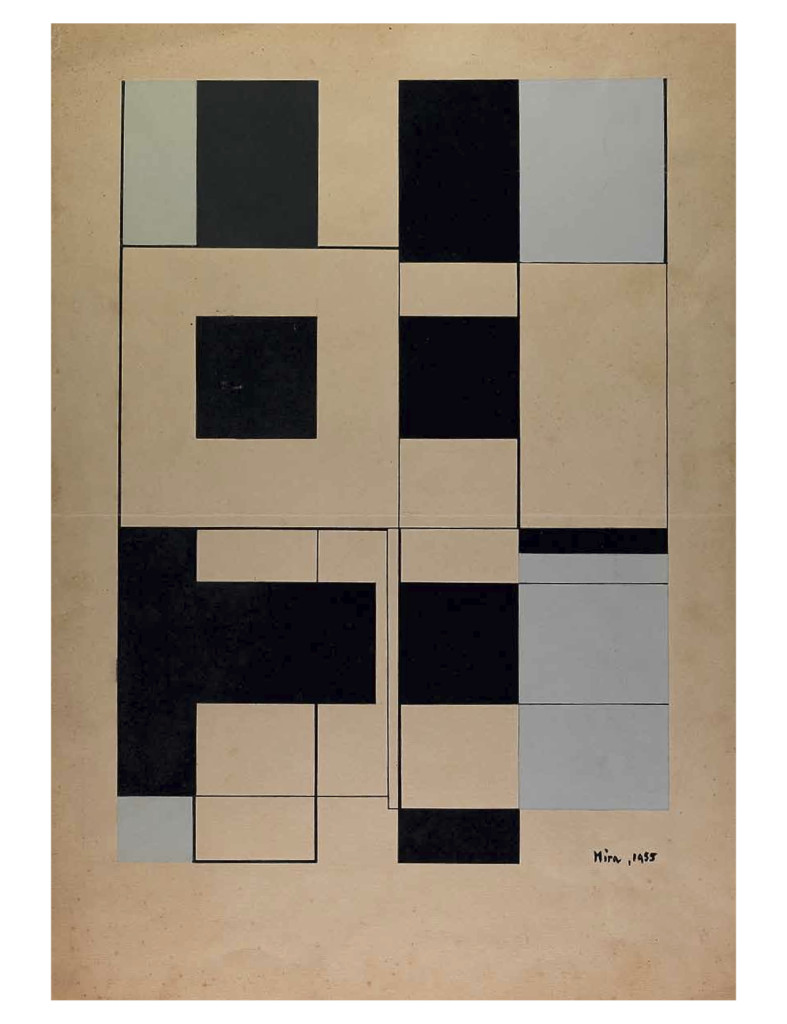

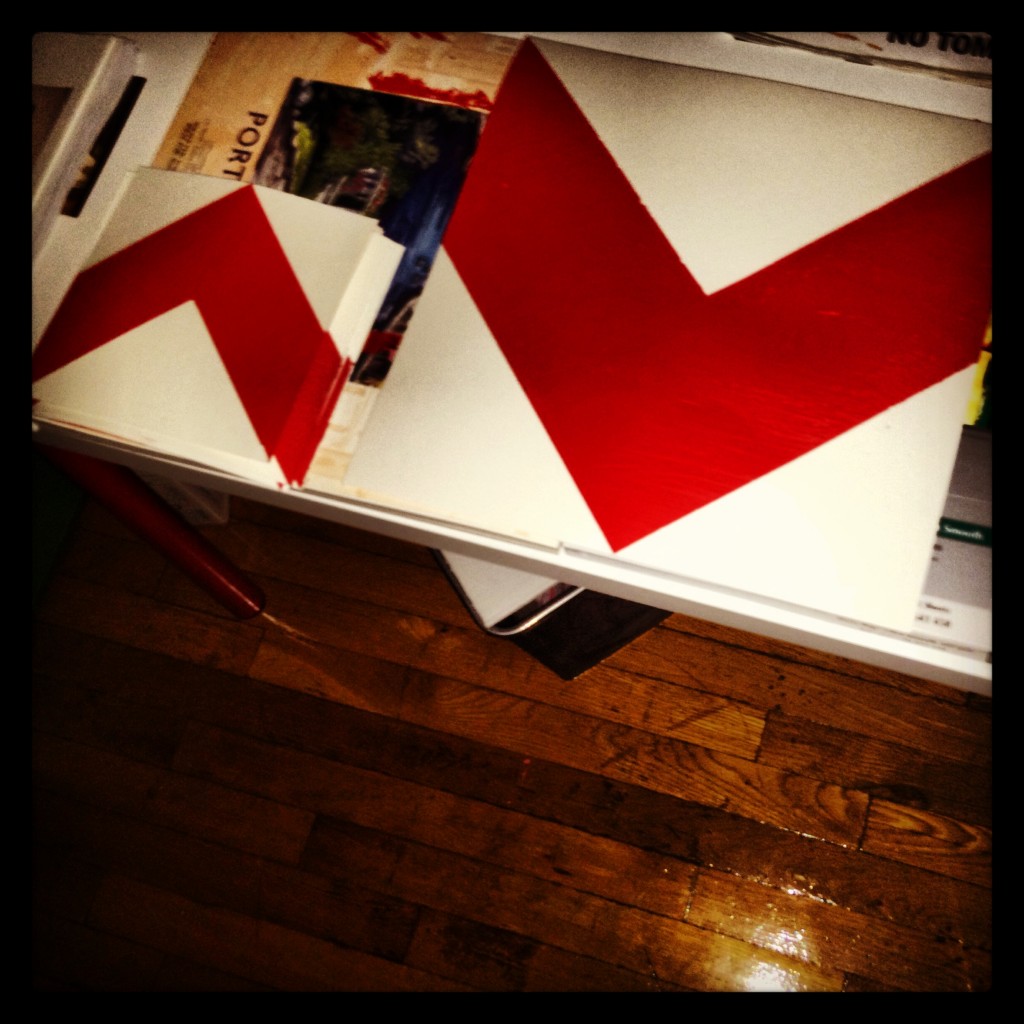

SENSITIVE GEOMETRIES – BRAZIL 50/80 @ Hauser & Wirth

CHELPA FERRO @ UNION SQUARE – NY

Summer Nights Series | art.br#2

Broadway to 4 Ave., E 14 St. to E 17 St. – Manhattan – New York CityAUGUST 15, 2013 > 8 PM > UNION SQUARE PARK

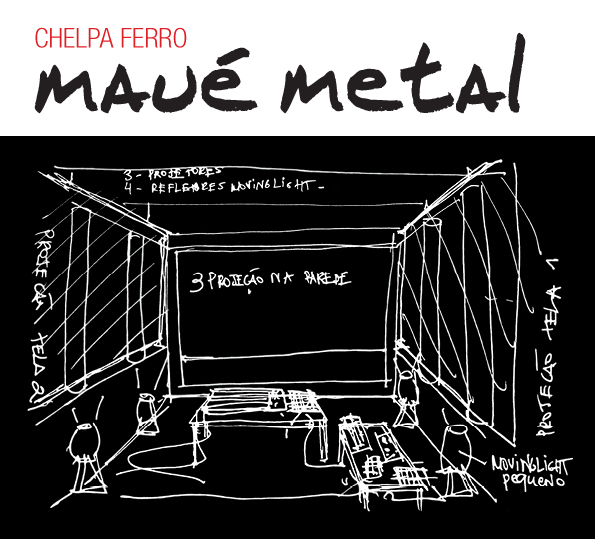

The performance Maué Metal by Chelpa Ferro is a sonic and visual

improvisation. Visual artists, who are not musicians, making sound.

Transforming noise into music, instruments into works of art. Maué,

an indigenous people of Amazonia, an autochthonous basis of Brazilian

culture. Metal, a rock’n’roll subtitle, of guitars and electronic instruments.

Maué Metal is the melding of two worlds. Tribal and technological,

of the past and the present.Daniel Rangel

Curator of art.br and Artistic Director of ICCoChelpa Ferro is: Barrão, Luiz Zerbini and Sérgio Mekler

chelpaferro.com.br | icco.art.br | arteinstitute.org

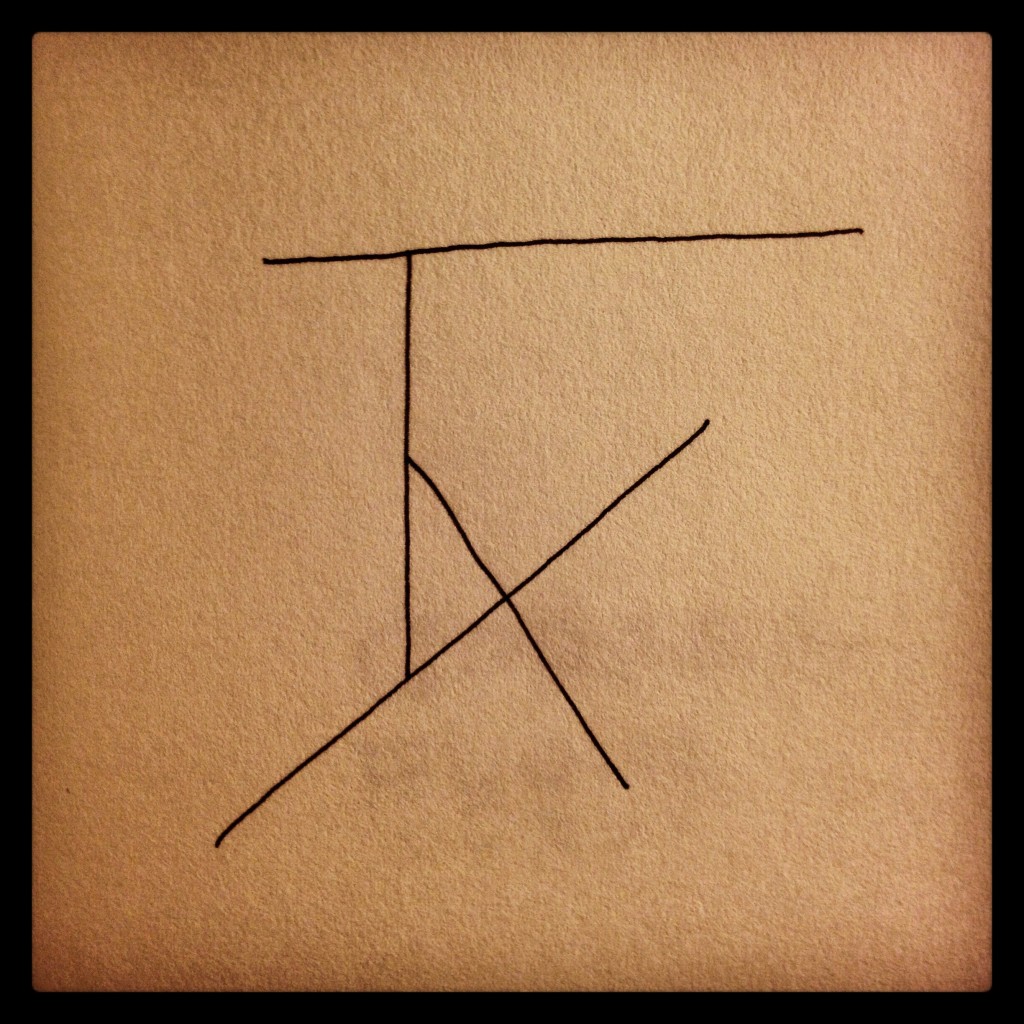

Image: sketch by Luiz Zerbini for the performance Maué Metal, 2013.

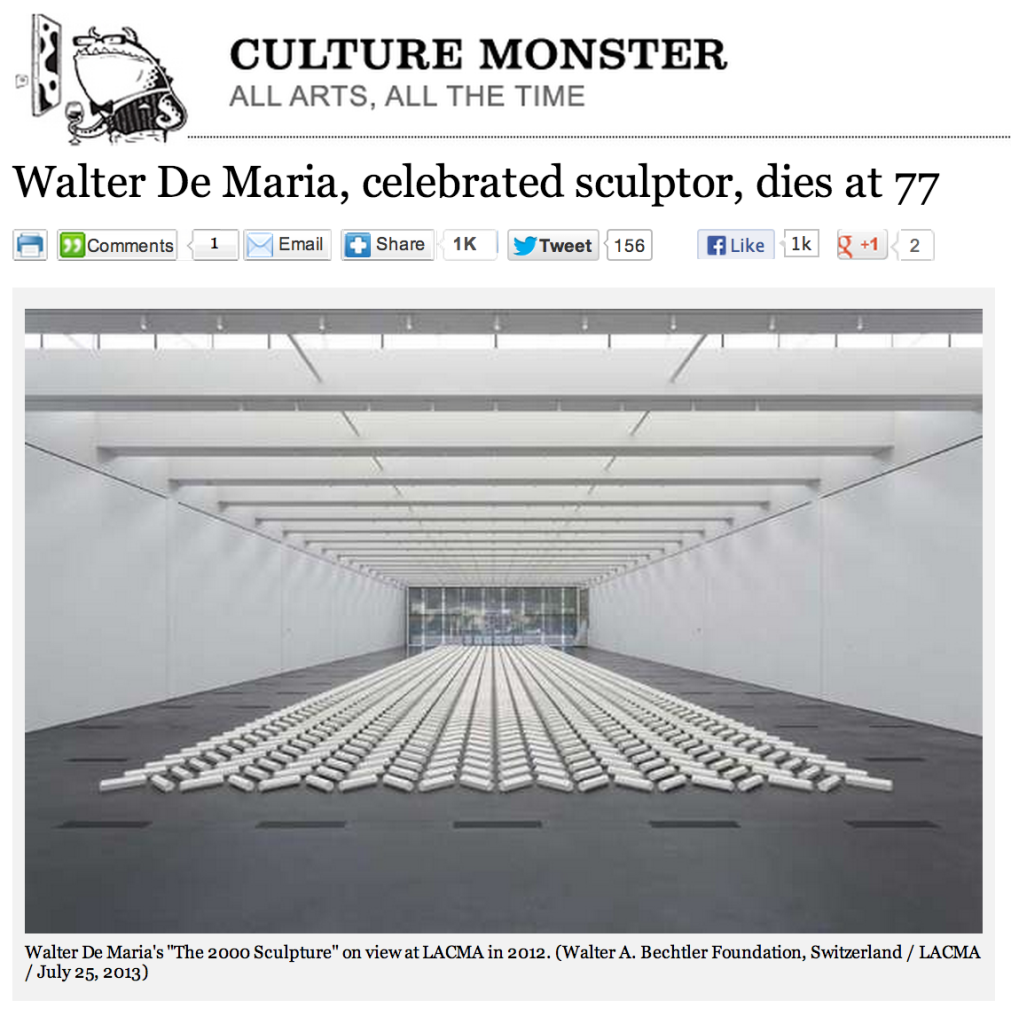

Walter De Maria, celebrated sculptor, dies at 77 By David Ng, LA Times

Walter De Maria, the artist and sometime musician whose monumental sculptures and installations combined the simplicity of minimalism with a love of scale, died Thursday at age 77. The cause of death was a stroke, according to his New York studio.

Throughout his career, De Maria cultivated a somewhat reclusive personality as far as the media was concerned. He seldom gave interviews and disliked being photographed. He also avoided participating in museum shows when he could, preferring to create his installations outdoors or at unconventional urban locations.

As a result, his work was not widely exhibited in the U.S. and he never became a household name. But critics championed his work, finding his large-scale installations to be conceptual and intellectually complex, while at the same time accessible to the general public.

His most famous creation was “The Lightning Field,” a land-art piece created in 1977 in New Mexico consisting of 400 polished stainless steel poles arranged in a rectangular array that is 1 kilometer long and 1 mile wide.

In October, the artist presented his installation “The 2000 Sculpture” at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, where it occupied most of the Resnick Pavilion. The piece consisted of 2,000 white rods arranged to form a geometric tesselation, creating different reflections of light.

“I think he’s one of the greatest artists of our time,” said LACMA director Michael Govan, who had worked with De Maria for a number of years. “I think there’s a quality to his work that is singular. It was sublime and direct.”

“The 2000 Sculpture” was used to test the light quality of Resnick Pavilion when it was preparing to open and was later displayed for the public.

Govan said De Maria shunned the media because “he wanted the work to stand for itself.”

The artist had a long working relationship with the Dia Art Foundation, which Govan headed in New York.

De Maria was born in Albany, Calif., and eventually settled in New York. His work was more widely shown abroad than in the U.S., and he had major exhibitions in Japan and Europe.

Some of his installations are still on view to the public. In addition to “The Lightning Field” in New Mexico, he created “The New York Earth Room,” at 141 Wooster St. in New York; and “The Broken Kilometer” at 393 West Broadway, also in New York.

In addition to his art career, De Maria was a sometime musician who played drums for the New York-based rock band The Primitives in the 1960s.

His survivors include his mother, Christine De Maria; his brother, Terry; three nieces; four nephews; and one grand niece.

Ralph Gibson + Larry Clark / curadoria Nessia Leonzini @ MIS, SP

O MIS apresenta a exposição Ralph Gibson & Larry Clark – Amizade, fotos e filmes. Com curadoria de Nessia Leonzini, a mostra celebra a longa amizade e o companheirismo profissional de dois dos maiores fotógrafos americanos da contemporaneidade.

Composta pelos vídeos mais contundentes da obra de Larry Clark, e trazendo um panorama completo da carreira artística de Ralph Gibson, a mostra traça um interessante paralelo entre a produção audiovisual e fotográfica dos anos 1960 aos anos 2000. Entre tantos nus esteticamente poéticos e fotos de sensualidade exuberante, o perfil minimalista e surrealista de Ralph estará em plena sintonia com a exploração da realidade juvenil, violenta e pungente que Larry retrata com maestria.

A mostra se completa com uma programação paralela que incluirá a exibição de todos os longas-metragens produzidos, roteirizados ou dirigidos por Larry Clark.

A curadora brasileira, radicada em Nova York, e o fotógrafo Ralph Gibson participam de um bate-papo com o público no Auditório MIS no dia 27 de junho, às 19h.

Sobre os artistas

Em mais de 40 anos de carreira, o fotógrafo Ralph Gibson mescla os estilos minimalista e surrealista em sua produção, sempre trabalhando em preto-e-branco e frequentemente retratando o erotismo. Tem mais de 30 livros publicados e 15 prêmios internacionais de fotografia, incluindo Leica Medal of Excellence Award (1988), “150 Years of Photography” Award, Photographic Society of Japan (1989) e Grande Medaille de la Ville d’Arles (1994).

Larry Clark, que em toda sua obra reflete a aspectos ligados à violência, sexo e drogas, tornou-se inicialmente reconhecido com o livro-documentário Tulsa (1971), que traz imagens do próprio artista e seus amigos usando drogas. Já seu interesse pelo cinema surgiu em 1993, após dirigir o videoclipe Solitary Man, de Chris Isaak. Sua estreia como diretor de cinema aconteceu em 1995, com Kids, filme controverso que manteve sua estética baseada na violência – e que ganhou prêmios como a Palma de Ouro em Cannes. Seu último filme, Marfa Girl, venceu o Festival de Roma em 2012.

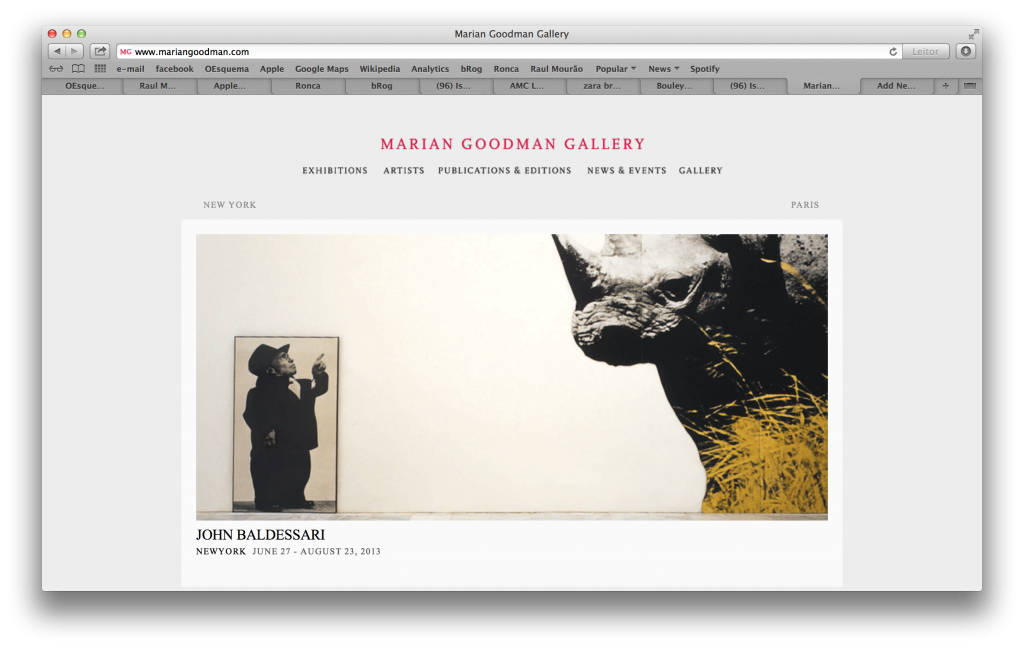

JOHN BALDESSARI INSTALLATION WORKS: 1987-1989 @ Marian Goodman

Marian Goodman Gallery is very pleased to announce a special exhibition of early installation works by John Baldessari for our summer exhibition.

The show will open on Thursday, June 27th and will run through August 23rd, 2013.

Created between 1987-1989, the composite photo works selected for this exhibition represent a key moment in Baldessari’s practice in which he introduced an architectural element to the work, expanding his strategic juxtaposition of overlapping fragments and chance correspondences to the creation and installation of work into a larger environment. Each of these works were shown at important and distinct exhibitions that were themselves defining moments spanning Baldessari’s oeuvre and artistic career.

Exploring correspondences and disparities of image and culture as well as the hierarchy of man in these artworks, Baldessari emphasizes the distinct separateness of each photographic image and the composition of a work from incongruous and disparate fragments in space. “So much of our thinking is shaped by certain givens”, explains Baldessari. “It is no accident that camera viewfinders are rectangles and that certain proportions shape our image of the world. I strongly believe that there is such a thing as hierarchy of vision that dominates the way that we picture reality. That is why for years my work has fought against what I term ‘the tyranny of the square.’ … ‘The use of frames as architecture is but an extension of the way I build my images up from psychologically charged material.’ (Baldessari in an article in Another Magazine by Mark Sanders, Autumn/Winter 2003).

The Difference between Fete and Fate, 1987 was first created as a special installation for the exhibition John Baldessari at Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Castello di Rivoli. Rivoli, Italy, May – June 1987. It has been reconfigured as a multi-wall installation in the North gallery, and is comprised of several groups of black and white photographs of animals and man.

Two Stories (Yellow and Blue) and Commentary (with Giraffe), 1989 is an installation of multiple components extending over three contiguous walls. The work’s central element is a column juxtaposing cinematographic references–an antecedent to later stack pieces–and is bordered on either side by photographic triptychs. An animal protrudes and wanders in from the periphery of the space, echoing the two photo images of the game of push-ball from Andre Gide’s Voyage au Congo of 1929. This work was shown in 1989 in the groundbreaking Magiciens de la Terre exhibition at Centre Georges Pompidou and Grande Halle La Villette, Paris.

The installation Dwarf and Rhinoceros (with Large Black Shape), 1989 shows three figures treated different ways: two dwarfs and one rhinoceros. The work was exhibited in the context of an exhibition devoted to the cultural memory of Spain, titled Ni por Esas/ Not Even So: John Baldessari shown at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, 1989. Writing in the catalogue, editors Guadalupe Echevarria and Vicente Todoli refer to this work: “One of the dwarves extends his index finger in a gesture reminiscent of Amosdeus, in Goya’s Black Paintings “Quinta del Sordo”. Asmodeus was seen as the demon of lust and anger, and like Mephistopheles, had secret abilities to discover hidden treasures and the power to become invisible. In his gesture (the Horned Hand), lay his power to control or hypnotize others…”. The installation was also presented at CAPC, Bordeaux and IVAM, Valencia.

This fall, the second volume of John Baldessari: Catalogue Raisonné, covering the years 1975- 1986 will be published by Yale University Press. Volume 1 which was released in May 2012 covered the years 1956 to 1974.

The artist will have a solo exhibition at The Garage CCC, Moscow, Russia from late September thru the end of November, 2013.

For further information, please contact the Gallery at: 212 977 7160.

O Travessias 2 acaba no próximo domingo, dia 23 de junho.

No sábado, dia 22, a partir das 19h teremos a festa de encerramento.

A programação é a seguinte:

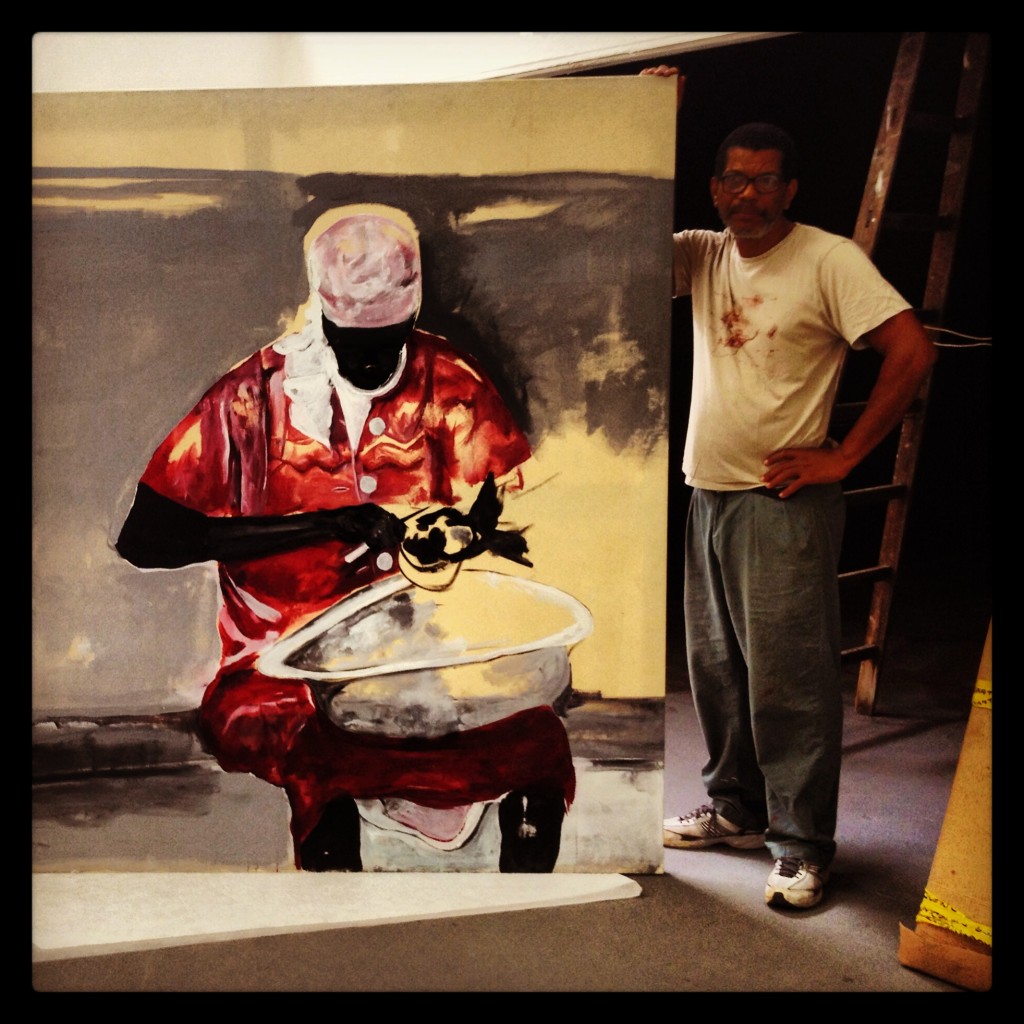

19h – Relato de artista: Arjan Martins

19h40 – Debate com Fred Coelho, Luisa Duarte (curadores do Travessias 10, Felipe Scovino, Jailson de Souza e Luiza Mello.

20h30 – Show da banda Dona Joana + Dj Flora Mariah com participação especial de Marcelo Yuka.

Vamos assistir o jogo Brasil x Italia no galpão do Centro de Artes da Maré. Quem quiser se juntar a nós será muito bem vindo.

VANS

15h: Automatica (Rua Gal. Dionisio, 53, Humaitá) – Maré

18h30: Baixo Gávea (em frente ao Braseiro) – Maré

19h30: Baixo Gávea (em frente ao Braseiro) – Maré

21h30: Maré – Baixo Gávea

22h30: Maré – Baixo Gávea

Contamos com a presença e a divulgação de vocês!

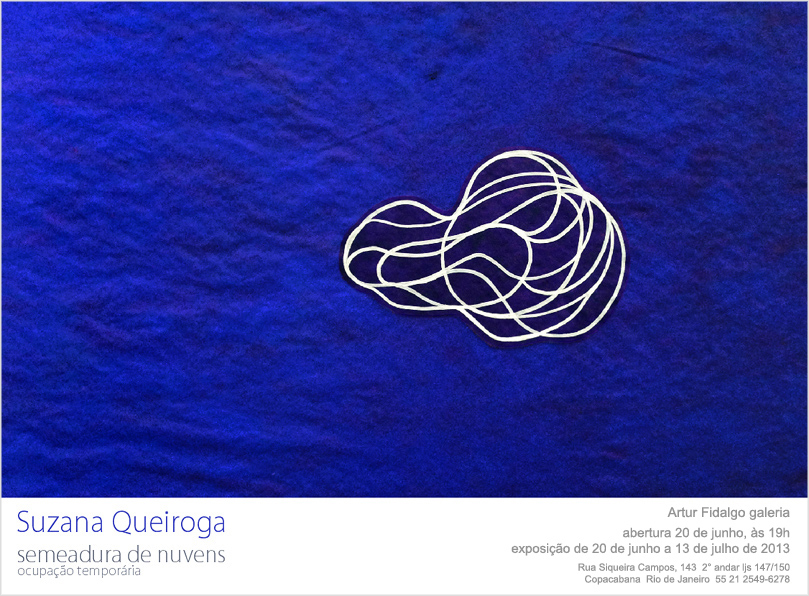

Suzana Queiroga no Artur Fidalgo

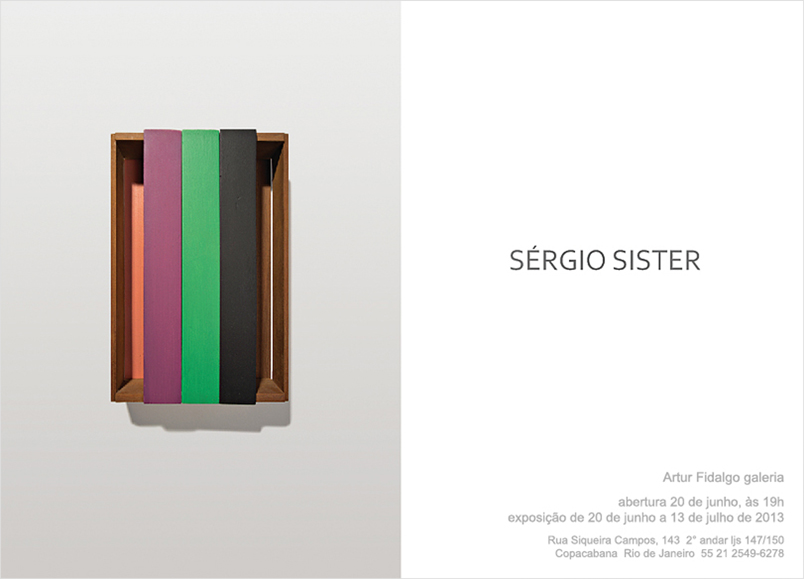

Sérgio Sister no Artur Fidalgo

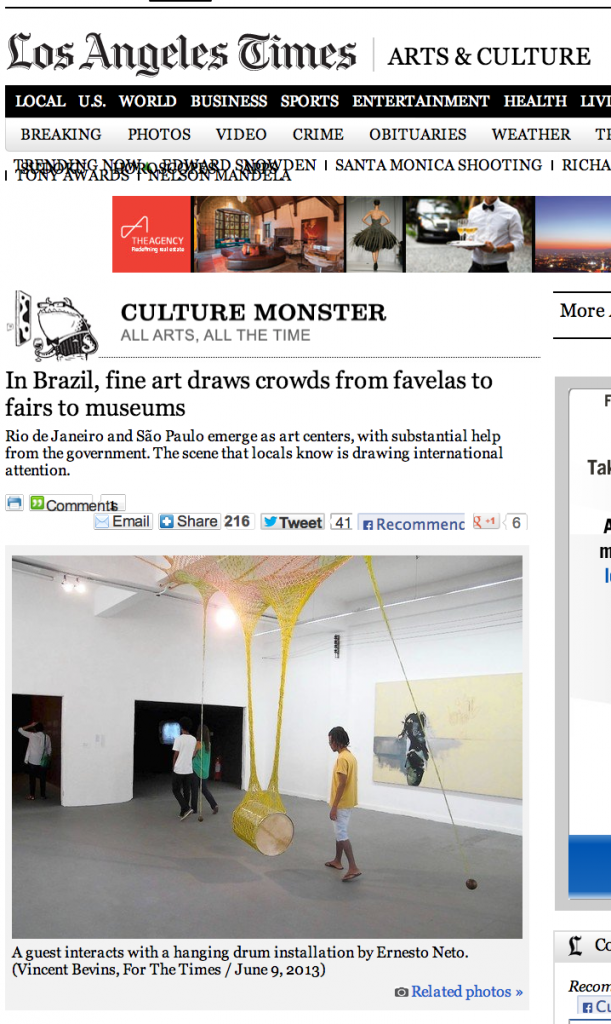

In Brazil, fine art draws crowds from favelas to fairs to museums by Vincent Bevins

Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo emerge as art centers, with substantial help from the government. The scene that locals know is drawing international attention.

RIO DE JANEIRO — Instead of playing in the dirty streets after school, one hot afternoon kids in a local favela, or slum¸ are led into a giant space with bright, high white walls. Assistants lead them around, nudging them to engage with original artworks including reflections on graffiti in their neighborhood and huge collages created by celebrated New York-based Brazilian artist Vik Muniz.

A drum hangs from the ceiling, as do two wooden balls. A docent tells the kids they are free to throw them against the instrument and asks them what’s the difference between them and an artist. They are artists now too, she says.

It’s not just here at the Travessias 2 exhibition in the Maré favela, put on by the government, nonprofits and the Automatica production company, that the power of fine art is popping up in Brazilian culture.

Exhibitions put on here are among the world’s most-attended and lines can stretch for hours as hot Brazilian artists sell for millions abroad and hundreds of local galleries now converge at one of two new art fairs in Brazil. All of this is not only because of the artistic nature of the country, critics say, but generous government support for the culture in a country which is now richer than ever.

“The only thing that hasn’t changed is the amount of talent in the country,” says Luiza Mello, director of Automatica. “What’s new is the amount of investments, the movement in the market, and the interest in the art.”

“There have long been music, dance and theater programs in favelas, but little with visual arts,” says Mello. “So we came up with the idea with NGO Observatório das Favelas [Favela Observatory], and Petrobras just said yes.” Petrobras is Brazil’s state-run oil company. Elsewhere, the government gives direct support or big companies get tax rebates to support cultural projects from slums to chic galleries and big public museums.

The Brazilian government spends at least $1 billion a year on direct support for the arts, and companies use almost as much annually in tax-deductible projects, says a spokesman for the Ministry of Culture.

Something seems to be working. In 2011 the Rio cultural center of Banco do Brasil, a government bank, had the world’s most-attended exhibition that year (“The Magical World of Escher”), and a show of famous Impressionists the center put on set records last year, according to the Art newspaper. Last year, Beatriz Milhazes’ hyper-tropical “My Lemon” set a new record for Brazilian art, selling for $2.1 million at a Sotheby’s auction in New York.

Hundreds of galleries now converge yearly on a new art fair in Rio, which has sprung up almost overnight alongside São Paulo’s established event.”It’s completely different than it was just a few years ago,” says Marina Romiszowska, head of curatorial affairs at ArtRio. “There’s more each month than anyone could attend.”

Over the last few years, Brazil’s new prominence on the world stage, after a decade of growth and as it prepares to host the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics, has meant much of the world is discovering Brazil’s talents, and state cash can promote them.

Some criticize the way the government supports the arts, since the tax-refund model allows big companies to slap their logos on projects that are essentially paid for with public money. And as the economy slows, there is worry the support may not last forever.

But the government is planning to soon launch a program that will give every worker in the country 50 reais ($25, or almost 10% of the monthly minimum wage) that they can spend exclusively on cultural activities, with the hope that it will allow average Brazilians to spend more time at museums, in the cinema, or at a live dance performance.

Art across society

Here in the favela, still plagued nearby by the dominance of drug gangs, they’ve put on an exhibition with 10 Brazilian artists, curated by the well-known Felipe Scovino and Raul Mourão. There are weekly talks bringing in people from all over the city as well as classes.

Just the day after Mello spoke in her office, there were two exhibition openings in Rio alone. At the Laura Alvim cultural center facing the beach in Ipanema, Marta Jourdan had put on a small show exploring permanent motion and French phenomenological philosopher Merleau-Ponty’s thoughts on image. The next night, São Paulo artist Alexandre Orion had fashioned his city’s famously aggressive graffiti, known as pixação, into garish neon light signs, to the delight of the young visitors who danced to hip-hop into the night.

These kinds of galleries have also benefited from special support from the state government, which granted a special tax exemption for all sales of art made during the new ArtRio fair

Little more than an idea in 2009, the first edition of the Rio fair in 2011 secured the tax break and the participation of 83 galleries. By the next year, organizers had to turn down interested galleries, and Romiszowska now flies around the world checking up on which galleries will make the cut. About 40% at September’s fair will be foreign.

“Even some really experienced curators and people from the art world had no idea about our scene and the way we do things until very recently,” she says. “But in general people are paying more attention to Brazil now, and everyone knows it’s nice to come to Rio.”

But the center of art is São Paulo, South America’s largest city, which holds the more established SP Arte, which showed more than 3,000 pieces last year in the building designed by Modernist Oscar Niemeyer, who died last year at 104.

The cutting-edge Pivô gallery has just sprung up in an abandoned space in his bold Copan building, and down the road the Galeria Vermelho (Red Gallery) continues to impress with contemporary artists from around Latin America.

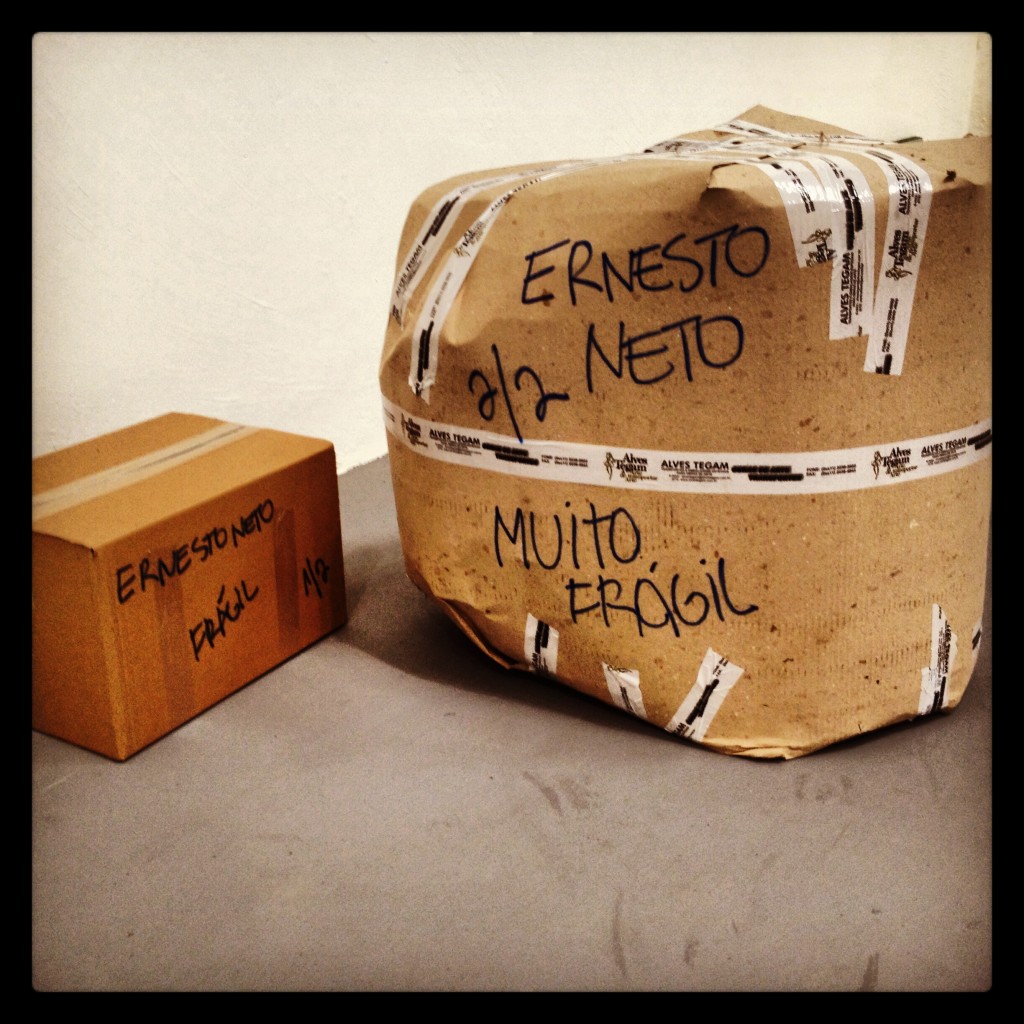

For large-scale commercial success, Adriana Varejão, Ernesto Neto, Milhazes and Muniz are some of the largest names. But Vermelho continues to push forward new artists.

“Vermelho seeks to act as a catalyst for what is most recent and innovative in art … creating new ideasand discourses developed by all kinds of artists,” says Marcos Gallon at Vermelho, in language reminiscent of that used by students of art worldwide. “Art created by Brazilians has reached more visibility abroad, and not through expositions of so-called Brazilian art, but also through the inclusion of Brazilians into universal themes.”

Modernism has deep roots in Brazil, which despite its 500-year history was not developed as a settlers’ colony and never had traditional feudal aesthetics dominate official culture as they did in much of the continent. How else could Niemeyer have been able to design Brasília, the country’s capital, in sculpted white concrete that looks more like a utopian settlement on Mars than any European parliament?

The Pinacoteca Museum of the State of São Paulo, considered by many the best in Brazil, seeks to balance the modernist impulse against works tracing the country’s history back to colonial time. Currently, the massive building downtown is hosting works from local painter Sérgio Sister, alongside a temporary exhibition of centuries of Chinese painting and selections from the permanent collection including Jean Baptiste Debret’s colonial era drawings of African slaves and Native American “savages.”

In the last five years, yearly attendance has more than doubled to 500,000 a year, and the museum is planning to expand, says Paulo Vicelli, its director of institutional relations. “In some ways we’re a very new country,” he notes, “but people want to be in touch with our collective memory too.”

Mel Bochner: Proposition and Process: A Theory of Sculpture (1968-1973) @ Peter Freeman, Inc.

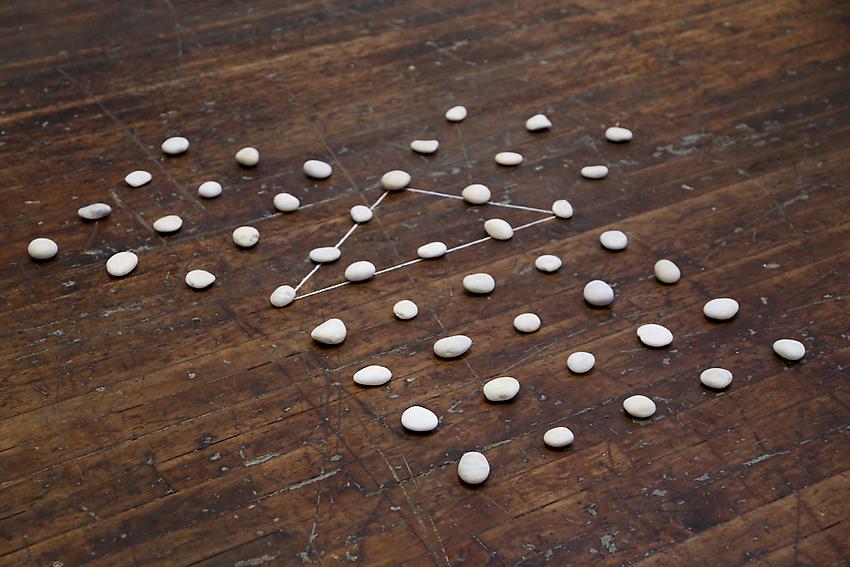

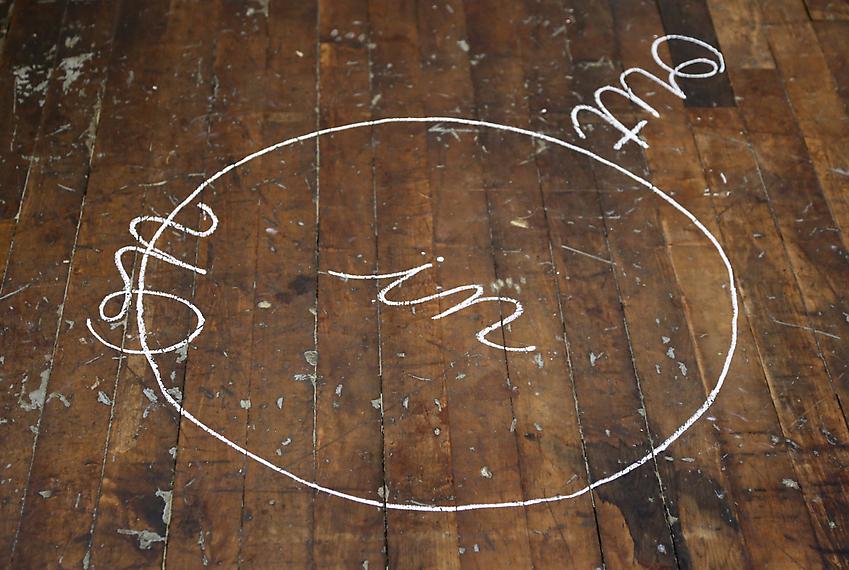

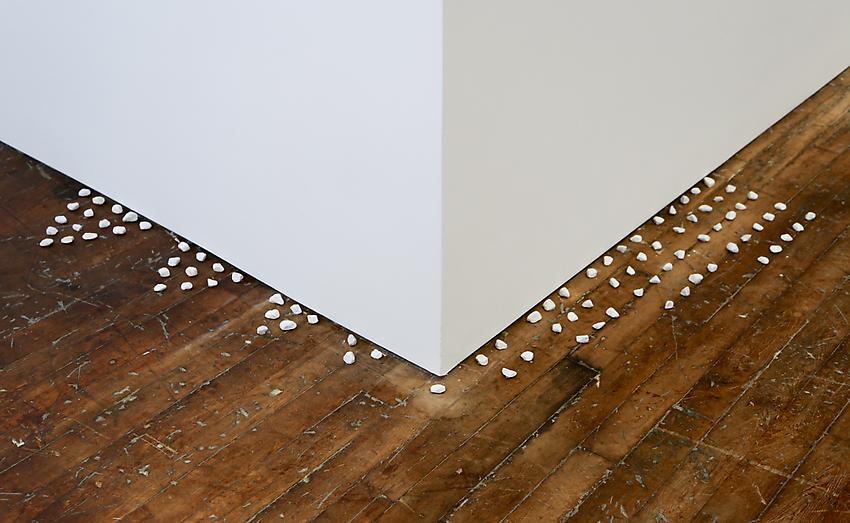

Peter Freeman, Inc. is pleased to present its fourth solo exhibition of work by Mel Bochner, which will be the largest survey of Bochner’s sculpture ever assembled. All from the years 1968 to 1973, these works represent the complete range of the artist’s investigations into the underlying conceptual foundations of sculpture; most have not been shown in New York since 1972.

About these works, Bochner wrote “Thoughts Reinstalling A Theory of Sculpture”:

A Theory of Sculpture is sculpture-as-self-representation. In these “self-representations” any material (pebble, nut, coin, match stick, glass shard, etc.) is replaceable without changing the intention. When an object loses its uniqueness, identity is denied an equivalence with presence. Any individual piece exists only as an “example of itself ”. Paradoxically, without the object there would be no idea, but without the idea there would be no object.

Number constitutes a mental class of objects. Numbers do not need concrete entities in order to exist. In Latin the word for counting is “calculus”, which translates, literally, as stone. By juxtaposing the numbers with the stones A Theory of Sculpture forces a confrontation between matter (“raw” material) and mind (categories of thought).

Sculpture, as opposed to painting, is defined by its alteration of the real world. In Latin the word for number is “digit”, which translates, literally, as finger. A Theory of Sculpture represents the hand (or agent of alteration), by the use of the numbers 5 and 10. Therefore, even though nothing is carved, cast, welded, constructed, or assembled, the manual aspect of sculpture is thematized.

The concerns in A Theory of Sculpture are not abstract. I am not interested in sculpture in any formal sense. The numbers and the stones exist on parallel but contradictory planes. While they appear to demonstrate the same thing there is a rupture between them. The map is not the landscape. An enormous abyss separates the space of statements from the space of objects. A Theory of Sculpture is the intention not to bridge that abyss.

(Mel Bochner, New York)

Mel Bochner was born in Pittsburgh in 1940, and received a BFA in 1962 from the Carnegie Institute of Technology. The work is represented in many public collections around the world, including Tate Modern (London), MoMA (New York), Whitney Museum (New York), Pompidou (Paris) and MUMOK (Vienna). Recent solo museum exhibitions include MAMCO (Geneva, 2003), the Art Institute of Chicago (2006) and the National Gallery of Art (Washington, 2011).

A major retrospective is currently on view at Haus der Kunst in Munich (until June 23) and will travel to the Museù Serralves in Porto (12 July – 13 October). Coinciding with this year’s 55th Venice Biennale curator Germano Celant will recreate Harald Szeemann’s seminal exhibition Live in Your Head. When Attitudes Become Form (Kunsthalle Bern, 1969) at the Fondazione Prada, where Bochner will reinstall “Thirteen Sheets of 8 ½ Inch Wide Graph Paper (from a nonfinite series)”. Also on view now in New York, located at 180 Bowery until September 29, Bochner has created a mural for After Hours 2: Murals on the Bowery, a project organized by the Art Production Fund.

lá no site Peter Freeman, Inc

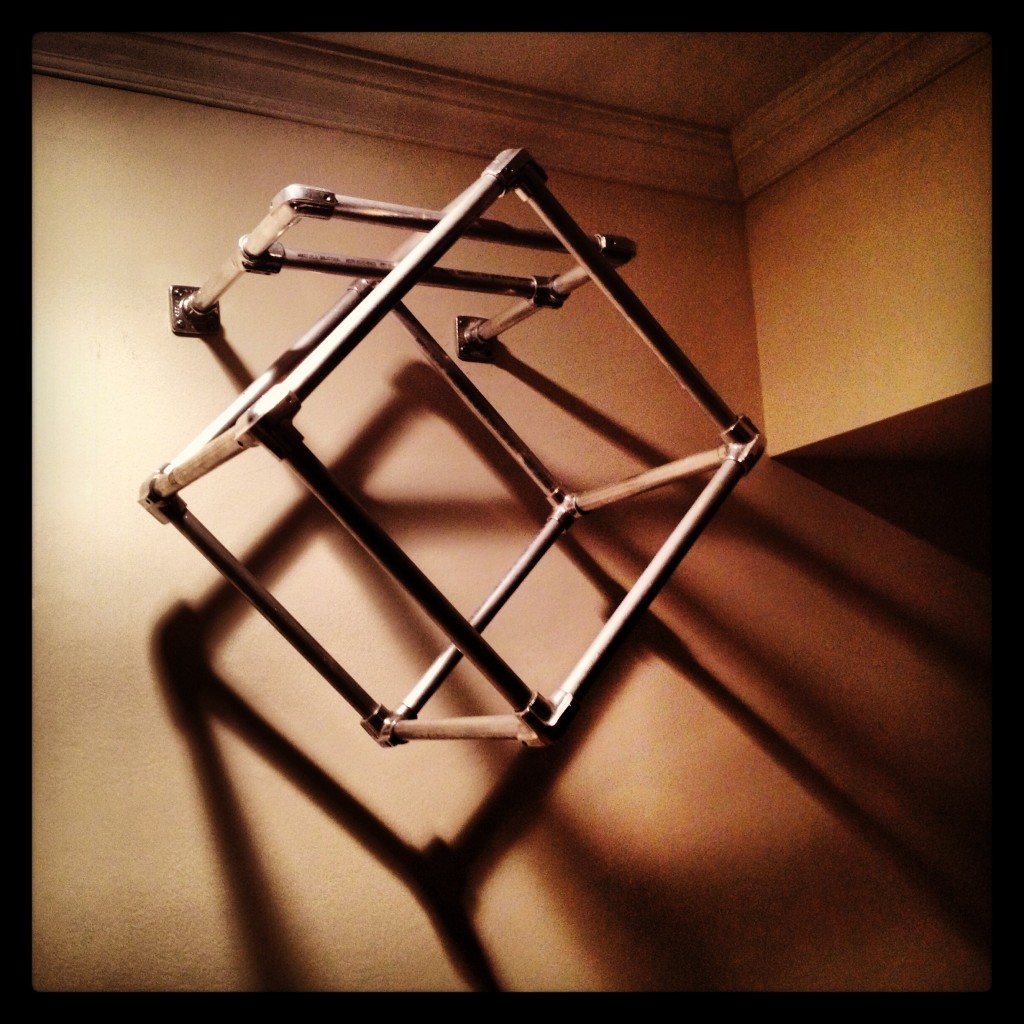

Judd Foundation Opens 101 Spring Street

Judd Foundation is pleased to announce the opening of 101 Spring Street in SoHo, New York for guided visits. The building was inaugurated on June 2, 2013 after a three-year restoration.

Purchased by Donald Judd in 1968, 101 Spring Street became his studio and primary residence, where he formalized his ideas regarding “permanent installation,” his philosophy that a work of art’s placement is critical to one’s understanding of the work itself.

Constructed in 1870 by Nicholas Whyte, the five-story building is the last surviving, single-use, cast-iron building in its neighborhood, a distinction that has earned 101 Spring Street the highest designation for national significance as part of the SoHo-Cast Iron Historic District. It is also among the founding sites of the Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios for the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Guided visits of 101 Spring Street will commence on June 18, 2013 and tickets can now be purchased through an online booking system. To book a visit, or for more information, please go to Judd Foundation’s website.

Guided visits for the general public will be available on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays. Custom visits for groups or individuals can be organized directly through Judd Foundation.

Please note: due to overwhelming demand, visits to 101 Spring Street are currently booked through August 2013.

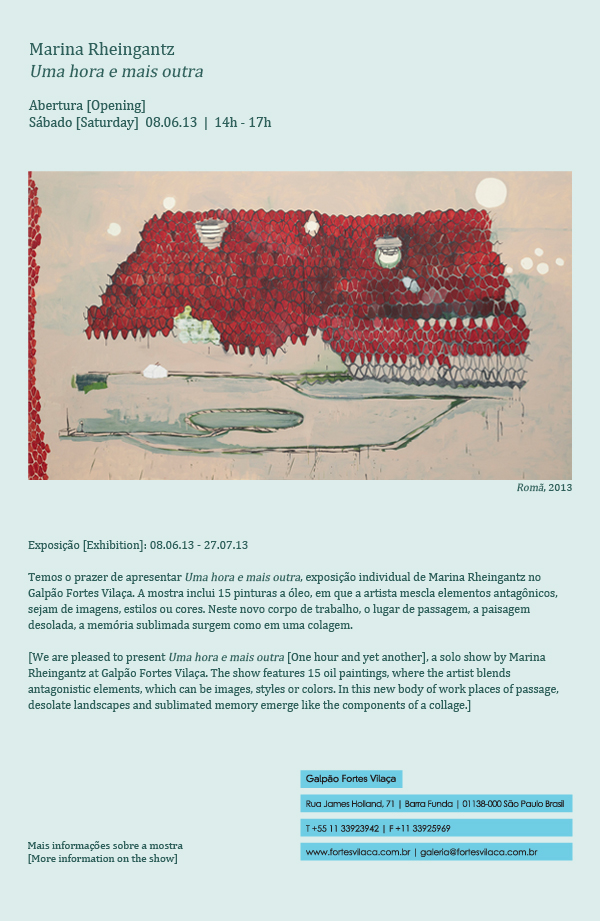

MARINA no GALPÃO

O POST DO MOMA

I. About post

post is a site for encounters between the established and experimental, the historical and emerging, the local and global, the scholarly and artistic. An online journal, archive, exhibition space, and open forum that takes advantage of the nonhierarchical nature of the Internet, post seeks to spark in-depth explorations of the ways in which modernism is being redefined. The site’s contents are intended to build nuanced understandings of the histories that shape the practices of artists and institutions today. As a networked platform, post aims to provide an alternative to the model of a unified art historical narrative.

post invites active participation! It is a space for sharing research and testing ideas, a platform for critical responses, and an instrument for increasing expertise through exposure to knowledge from around the globe. post is designed to produce a changing and layered articulation of multiple modernities, which will emerge over time as more people from more places participate. While post takes as its starting point research undertaken at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), it will continue to seek and develop a network of engaged partners and users whose complementary research and concerns will shape future approaches and content. New essays, interviews, reports, and reflections, as well as archival materials and artists’ commissions, will be released regularly to ensure that new voices enter the debates and new research concentrations continue to emerge.

II. About C-MAP (Contemporary and Modern Art Perspectives in a Global Age Initiative)

post begins as the public face of C-MAP, a cross-departmental research program launched in 2009 to expand our reading of art history and, consequently, what we do at MoMA. The scope and methodologies of C-MAP research question the judgments that grow out of the assumption that artistic modernism is or was determined only by the Western European and North American narratives of early twentieth-century avant-gardes. The aim of C-MAP is to understand more fully the historical imperatives and changing conditions of transnational networks of artistic practice and to seek verbal and material accounts of histories that often have been little known outside their countries of origin.

C-MAP’s core working structure is the long-term research group. Currently, there are three research groups focusing respectively on Central and Eastern Europe, Asia (with a particular focus on Japan), and Latin America, regions with strong histories of modernism. These groups are led by Christophe Cherix, Doryun Chong, and Jodi Hauptman, respectively. The groups’ members include senior and junior staff from all curatorial departments, the library, the archives, and the Department of Education. They are joined by three international scholars with multiyear fellowships—Magdalena Moskalewicz, Miki Kaneda, and Zanna Gilbert—as well as visiting scholars, curators, and artists to create cross-disciplinary investigations. In addition, three distinguished scholars serve as counselors for the initiative: Mieke Bal, Professor of Humanities, Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, Universiteit van Amsterdam; Homi Bhabha, Anne F. Rothenberg Professor of the Humanities at Harvard University; and David Joselit, Carnegie Professor of Art History at Yale University. Group members travel together to deepen their understanding of the specific qualities and histories of the places they are studying. Each trip involves dozens of meetings with artists and specialists, including those who have participated in seminars at MoMA.

C-MAP forges new relationships and partnerships and undertakes collaborative research in order to develop new expertise, share what has been learned, and ultimately, inform the development of exhibitions, publications, educational programs, and the collection, for the benefit of scholars, curators, educators, students, critics, artists, and the general public alike.

The Museum of Modern Art’s Contemporary and Modern Art Perspectives in a Global Age Initiative (C-MAP) is supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and The International Council of The Museum of Modern Art.

Additional funding is provided by Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, Adriana Cisneros de Griffin, and Marlene Hess.

For questions or comments, please contact us at Contact_C-MAP@moma.org.

post is designed and developed by TC Labs. The post platform was conceived in collaboration with Caleb Waldorf.

Casa Daros abre edição do programa Diálogos

Em conversa aberta ao público, Iole de Freitas falará sobre sua pesquisa “Para que servem as paredes do museu – a relação entre instituição e artista”, com a diretora-geral da Casa Daros, Isabella Rosado Nunes, e Eugenio Valdés Figueroa, diretor de arte e educação.

A Casa Daros apresenta, no próximo dia 08 de junho de 2013, o programa Diálogos, com a participação da artista Iole de Freitas (1945, Belo Horizonte) e dos diretores Isabella Rosado Nunes e Eugenio Valdés Figueroa. O tema será a pesquisa da artista “Para que servem as paredes de um museu?” e sua relação com a instituição, que envolveu o processo de criação da escultura “Sem título“ (2011/2013), um “site specific” de cem metros quadrados, com quatro metros de altura, em policarbonato e tubos flexíveis de alumínio, instalada na exposição “Para (saber) escutar”. A escultura, resultado da primeira residência de pesquisa na Casa Daros, fica em exposição até o dia seguinte, 09 de junho.

No projeto da Casa Daros, a ideia inicial de Iole de Freitas foi acompanhar o processo de transformação do edifício que abriga a instituição e imaginar “utopias para lugares que estão mudando, junto com as ideias”. A artista se dedicou a pensar esculturas, instalações e situações impossíveis de serem feitas em um espaço que sofre alterações permanentes. “As esculturas dependem, em geral, de ancoragens onde possam estar em equilíbrio”, observa Eugenio Valdés Figueroa, diretor de arte e educação da Casa Daros. “Para realizar este trabalho, houve um intenso diálogo entre a artista e a instituição, já que a Casa Daros está instalada em um prédio tombado pelo patrimônio municipal”, acentua Isabella Rosado Nunes.

Iole de Freitas conta que a referência de seu trabalho que está em exposição foi o mar, e que pesquisou dois tons de verde – um com mais amarelo, e outro com mais azul – presentes na instalação suspensa. “Para a pesquisa realizada inicialmente, em 2011, nos jardins eu investiguei a verticalidade produzida pelas altas palmeiras imperiais, mas agora, para o interior da sala de exposição busquei o elemento água, e os seus muitos tons de verdes”, explica a artista. Iole fez vários testes até encontrar os dois tons de verde que queria. Ela buscou um movimento fluido, e o resultado dá a ideia de “velocidade, de turbilhão”, explica. A face voltada para cima do policarbonato – material que sempre utiliza – é translúcido, e reflete a luz e a arquitetura em volta, um elemento emblemático da instituição.

A obra de Iole de Freitas fica até 09 de junho. A partir de 21 de junho a sala de residência artística abrigará as obras que integram o projeto “A guerra que não vimos”, do artista Juan Manuel Echavarría, até 18 de agosto de 2013. A exposição “Para (Saber) Escutar”, paralela a “Cantos Cuentos Colombianos”, ocupa as cinco salas de arte e educação do primeiro andar da Casa Daros, e permanece até o próximo dia 28 de julho de 2013.

Programa Diálogos Casa Daros

Participação Iole de Freitas, Isabella Rosado Nunes, Eugenio Valdés Figueroa

Casa Daros, Rio

[Auditório]

8 de junho de 2013, das 17h às 18h30

Entrada gratuita

Senhas distribuídas uma hora antes do evento

Capacidade: 91 pessoas

Rua General Severiano, 159, Botafogo, Rio, CEP 22290-040

Telefone: 21.2138.0850

De quarta a sábado, das 12h às 20h

Domingo e feriados, das 12h às 18h

Exposição “Cantos Cuentos Colombianos”

Até 08 de setembro de 2013

Ingresso: R$12,00 / Idosos e estudantes com mais de 12 anos: R$6,00

Quartas-feiras: entrada gratuita

Bilheteria fecha meia hora antes de encerrar o horário de visitação

Exposição “Para (saber) escutar”

Até 28 de julho de 2013

Entrada franca

Sarah Sze: The Stones of Venice By Carol Vogel NYT

clique aqui para ver o video > http://nyti.ms/11ypyHs

VENICE — Everyone is anxiously waiting to get into the Biennale, which opens to the art world here on Wednesday and to the public on Saturday. But those who have already arrived can take an early peek at the work of one artist.

Perched on balconies and rooftops around the city, in shop windows and even on the shelf of a gelato stand are beautifully fashioned rocks.

Convincingly real, these stones are the creation of Sarah Sze (pronounced ZEE), the artist who is representing the United States at the Biennale this year and whose installation fills this country’s pavilion. “I wanted the installation to bleed out into the environment,’’ she said on Monday as she led a group of visitors around the Via Garibaldi. “So I asked people if they would be willing to put them in stores or on balconies, and everyone said yes.”

Ms. Sze photographed real rocks, took the images and printed them on Tyvek, a strong synthetic material. She then covered aluminum structures with her rock pictures.

The local recipients are enjoying their artworks. Jacobo Chiozzoto has a boulder on the roof of his newsstand. “When people ask what it is, I give different answers depending on who wants to know,” he said with a laugh. “Sometimes I say it’s to hold down the roof; other times I tell people it’s an asteroid.”

In this video, we look at some of those rocks and hear about Ms. Sze’s process. We also get an early look inside the United States pavilion, a series of rooms with carefully constructed assemblages, including a planetarium-like space, a room with sinking desks and a setting that resembles an artist’s studio.

TIMELINE #7

12 Years of DFA: Too Old To Be New, Too New To Be Classic

VICENTE DE MELLO – Silent City

J’ai vécu ma résidence, à l’invitation de l’Espace Photographique Contretype, comme un atelier en plein air, avec Bruxelles comme sujet principal.

C’était mon second séjour, le premier ayant eu lieu en 1999, où j’avais passé 48 heures dans la capitale considérée comme un joyau européen. En 2012, un fait culturel m’a frappé, c’est le silence de cette ville, tellement éloigné des villes brésiliennes, où la présence humaine entraîne toujours une profusion sonore. Ce silence a été la piste qui m’a conduit à «trouver» les images qui se dévoilaient à moi lors de mes balades.

J’avais tout mon temps, car j’étais seul à Bruxelles, de jour comme de nuit. Le temps de faire des photographies, de faire des tours en ville, du temps à écouter la chaîne Musiq 3 la nuit, lorsque le froid extrême vous contraint à vivre face à vos propres démons.

Dans la lumière du soleil, la perception des reflets et des ombres, rendus par la ville, révèle un univers différent, tel un film noir secret, où le danger, les mystères et les secrets sont tapis dans l’ombre.

Bruxelles dit: «déchiffre-moi ou je te dévorerai»! C’est ce sentiment que j’éprouvais, de vivre ailleurs et ayant du temps à consacrer à la contemplation. Chacune de mes photographies est un territoire conquis, une représentation personnelle du monde, avec son intention, avec laquelle j’exprime ma position face à la nature destructive de l’espace, pour ensuite être construite et articulée par le spectateur.

Les images réalisées pour Contretype constituent une nouvelle série intitulée «Silent City »; elles ont été prises avec un appareil Rolleiflex, tout comme les images de mes autres séries La nuit américaine, d’Après, Galactic, et Contrejour.

Toutes mes photographies portent par un titre faisant référence au dicible et au visible, comme une narration de leur «âmes picturales», soulignant l’expression du concept qu’elles contiennent. Ainsi est la description du monde, par la parole ou l’image.

Pour faire une image, le hasard est la meilleure opportunité: mesurer mentalement la lumière, risquer, savoir que cela ne pourra pas se reproduire, mais le faire, ensuite voir le résultat. Je trouve que ma démarche de photographe qui a déchiffré Bruxelles est bien différente de celle de l’écrivain qui écrit et corrige, de l’acteur qui expérimente à chaque représentation.

Vicente de Mello

New Guide in Venice by Carol Vogel – NYT

By CAROL VOGEL

Published: May 23, 2013

Massimiliano Gioni, the artistic director of this year’s Venice Biennale, was marveling at the rich history of this 118-year-old international contemporary art exhibition.

“Klimt showed there in 1905,” he said. “That is mind-blowing to me. Since then there has been Morandi and Picasso, Rauschenberg, Johns and so on. Maybe I’m romanticizing, but the past is still very present.”

On a rainy afternoon in April Mr. Gioni was having lunch at his regular haunt, a tiny Italian restaurant in Lower Manhattan near the New Museum, where he is associate director and director of exhibitions. His BlackBerry was buzzing with e-mails and his phone kept ringing. Yet Mr. Gioni, 39, ignored it all, speaking earnestly with his usual intellectual intensity jolted with unexpected moments of deadpan humor. He was explaining what it’s like to be the youngest artistic director in 110 years to organize the first, oldest and most venerable international art event in a calendar packed with an unrivaled number of them.

“Of course I’m nervous,” he said. “This is center stage and it’s difficult because it comes with so many expectations and so much history.”

As he braces for the art world to descend on Venice for three preview days beginning on Wednesday, followed by the public opening on Saturday, Mr. Gioni estimated that nearly 500,000 people would come to see the Biennale by the time it ends on Nov. 24. As artistic director, his job is not only to be the diplomatic face of the Biennale but also to organize an enormous exhibition in two sites: one in a central building in the shaded gardens at the tip of Venice where the national pavilions are, and the other in the nearby Arsenale, the meandering medieval network of shipyards. The job entails an overwhelming amount of juggling and his ambitious vision has only made it worse.

Even though Mr. Gioni was born in Italy — in Busto Arsizio, 40 minutes northwest of Milan — the logistics of working in a city like Venice are a notorious nightmare. Adamant that this will not be a boiler plate survey of contemporary art, Mr. Gioni has enlisted 158 artists, nearly double the number of the two previous Biennales.

“It will zigzag across histories, covering 100 years of dreams and visions,” said Mr. Gioni, noting 38 countries are represented. “A biennale can be pedagogical without being boring.”

“The Encyclopedic Palace” is the theme. It is taken from the title of a symbol of 1950s-era Futurism — an 11-foot-tall architectural model of a 136-story cylindrical skyscraper that was intended to house all the knowledge in the world. Its creator, the self-taught Italian-American artist Marino Auriti, dreamed it would be built on the National Mall in Washington. The model now belongs to the American Folk Art Museum in Manhattan, which is lending it to the Biennale. “It best reflects the giant scope of this international exhibition,” Mr. Gioni said, “the impossibility of capturing the sheer enormity of the art world today.”

Paolo Baratta, the longtime president of the Biennale, said that “after 14 years of having traditional curators I thought it was time to ask a man of the next generation.”

“At a time when contemporary art is flooding the world,” he added, “it seemed to make more sense to present a show that doesn’t just include a list of artists from the present but rather looks at today’s art through the eyes of history.”

Philippe Ségalot, a private art dealer, called Mr. Gioni “a rising star.”

“Even though he’s so young,” Mr. Ségalot said, “he’s already a brand and one of the most sought after curators around. As a result expectations are unusually high. Everyone wants to see what he’ll deliver.”

Mr. Gioni is mixing high and low, with masters mingling with self-taught and outsider artists. Besides Mr. Auriti, there will be work by names likely to be unfamiliar to even art world insiders. There are arcane objects like a deck of tarot cards created by the British occultist and artist Aleister Crowley, abstract paintings by the Swedish artist and mystic Hilma af Klint and shaker drawings on loan from the Hancock Shaker Village in Pittsfield, Mass. For one show within a show, the photographer Cindy Sherman is organizing an exhibition at the Arsenale. Known for photographing herself transformed into hundreds of different personas, including movie stars, Valley girls and menacing clowns, she appealed to Mr. Gioni because, he said, “image plays a big role at this year’s Biennale, and Cindy has spent her life representing herself as others.” Ms. Sherman is creating a kind of bizarre doll’s house with works by little-known artists, prison inmates and popular figures like Robert Gober, Charles Ray, Paul McCarthy and Rosemarie Trockel.

An old ship is coming by boat from Iceland; a 200-year-old church is en route from Vietnam; and dozens of contemporary artists need hand-holding while they grapple with installing videos or preparing for complex performances. “Right now I wish there was another me,” Mr. Gioni said with a sigh.

Besides organizing the event he has also been a fund-raiser. Money is always tight at any Biennale, and his budget of about $2.3 million simply wasn’t enough to cover his expenses. He has raised more than $2 million on top of that, he said, “mostly from private individuals and foundations and philanthropists.”

Although Mr. Gioni is considered something of a star within the close-knit world of contemporary art, he had a larger presence early in his career as the doppelgänger of the mischievous Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan. Mr. Cattelan, who is more than a decade older, routinely sent him in his place to do radio and television interviews and even lectures. The prank worked for a while, Mr. Gioni recalled, until a series of mishaps. He was speaking at a lecture organized by the Public Art Fund when Tom Eccles, its director, showed slides of Mr. Cattelan’s self-portraits. “It was obvious I wasn’t him,” Mr. Gioni recalled.

Then there was the time he posed as Mr. Cattelan on television and the station’s switchboard became jammed with viewers complaining that an impostor was on the air.

“Maurizio was so in demand and I liked it because I thought it was a way to be a committed critic, giving your words to an artist,” Mr. Gioni said.

Less than a month before the Biennale was set to open, Mr. Gioni could be found sitting around the dining room table of his apartment, a spare sun-filled East Village walk-up that he shares with his wife of three years, Cecilia Alemani, director of art at the High Line. With him were three assistants, each glued to laptops. Wearing jeans, a white shirt and red sneakers, Mr. Gioni had a way of juggling complex issues with a cool head, quoting wise words from a philosopher one moment and making a wry joke the next. The group was reviewing each artist in the exhibition, name by name, and checking the status of their work.

What about Roger Hiorns? Mr. Gioni asked.

“He’s concerned his installation will be too near a door,” replied Helga Christoffersen, an assistant.

Mr. Gioni explained, “It’s a pulverized altar from a church from England.”

“That’s going to be a big hit with the Catholic folks,” he said deadpan, receiving a big laugh from the group. (For the first time the Vatican is represented in its own pavilion at the Biennale.)

Camille Henrot? “Missing in action,” Mr. Gioni said slightly nervously.

The group then looked at images online of the “S. S. Hangover,” the Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson’s fishing boat that will have six horn players performing on the water in the Arsenale for four hours every day for six months. “We’re working with a conservatory in Venice to find the players,” Mr. Gioni said.

When trying to visualize the installation of the circular entrance in the main pavilion where he plans to display 40 pages of Carl Jung’s “Red Book,” an illuminated manuscript on which he worked for more than 16 years, Mr. Gioni grabbed a ruler, went into the living room and measured out the space on the floor with masking tape, trying to figure out the correct height for the climate-controlled vitrine.

“He’s obsessed,” Mr. Cattelan said. “When he gets in bed at night he’s not just thinking about the big picture but also about the number of electrical outlets or the height of a video. He gets caught up in the details most curators normally don’t take care of. Being super bright helps; so does his superior knowledge of art.”

Mr. Gioni’s methods may be a bit unconventional, but then he didn’t come to the job in the same way as many of his predecessors. He never got a Ph.D. in art history; nor did he spend years climbing his way up the curatorial ladder. But at 39 he has had more hands-on experience overseeing biennales than anyone of his generation: In 2003 he was the curator of the section called “La Zona” at the Venice Biennale. In 2004 he was co-curator of the fifth edition of the traveling biennial Manifesta, a roving European event that was held that year in San Sebastián, Spain; in 2006 he organized the fourth Berlin Biennale in collaboration with Mr. Cattelan and Ali Subotnick, a curator at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. And in 2010 he was the youngest and first European director of the Gwangju Biennale in South Korea, its eighth, which attracted more than 500,000 visitors and got rave reviews.

Besides his role at the New Museum, where he has spearheaded many ground breaking shows including “The Generational: Younger Than Jesus,” its first triennial, he is also artistic director of the Nicola Trussardi Foundation in Milan. Lisa Phillips, director of the New Museum, said Mr. Gioni “sees curating as an art form.”

“He is terribly well read without being academic so that he can cut across centuries and create a new story,” Ms. Phillips said.

Although it all sounds like pretty serious stuff, but Mr. Gioni has a lighter side too. In 2002 Mr. Gioni, along with Mr. Cattelan and Ms. Subotnick, started “The Wrong Gallery,” a minuscule space that was little more than a doorway with a classic Chelsea aluminum-glass front door on West 20th Street. (In 2005 the spoof gallery was evicted, then decamped to the Tate Modern in London in 2005, closing three years later.)

Mr. Gioni’s parents are retired — his mother was a schoolteacher and his father was the manager of an ink factory. When he was 15 he moved on his own to Vancouver Island in Canada, where he attended the United World Colleges; later he received a degree in art history from the University of Bologna. The youngest of three siblings, he describes himself as the black sheep of the family.

To support himself through school he worked as a translator and eventually became editor of the Italian edition of Flash Art, where he met Mr. Cattelan; in 1999 he moved to New York as its American editor. He met Francesco Bonami, now an independent curator, and did some work with him. Mr. Bonami was the artistic director of the Venice Biennale in 2003 and it was he who asked Mr. Gioni to organize “La Zona” there. Ms. Phillips hired him at the New Museum in 2006 after seeing the Berlin Biennale, which she called “a standout.”

Despite the instantaneous nature of culture today and the proliferation of art fairs and giant exhibitions, Mr. Gioni still believes there is a place for biennales. “I grew up with them,” he said. “I saw my first one in Venice in 1993. They are no longer a fixed formula. This is the first decade of a new century and this show will deal with our age of hyperconnectivity, by looking at what goes on in our heads rather than online. It is about the synchronicity of the past, the present and the future.”

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

Correction: May 23, 2013

An earlier version of this article and an accompanying caption misstated the age of Massimiliano Gioni. He is 39, not 40. The article also misstated the employment status of Ali Subotnik. She is a curator at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles — not an independent curator.

Daniel Steegmann Mangrané na Galeria Nuno Centeno

“/ (- \”

last days > saturday 25 / sunday 26 (only by appointment)

Nuno Centeno Gallery is pleased to present for the first time in Portugal the Brazil-based catalan artist Daniel Steegmann Mangrané with the exhibition “/ ( – \”, which appeals to transit states and deals with notions of corporeality and immateriality.

“/ ( – \” fills completely the gallery space and it is composed by a set of 4 curtains, half industrial and half handmade. The material of the curtains is original from south Catalunya where the artist spent his summers. Widely used there in butcher shops and on the home’s front doors, Kriska aluminum curtains have the ability to be traversable and close quickly after the viewer’s passage, in addition to its characteristic metallic noise. The holes in the curtains invite the viewer to go through them in silence or traverse the curtain making noise.

The curtains divide the space into four sections, and operate both as an independent sculptures and as elements of a larger installation, creating a work that dematerializes in the relationships established between the viewer’s body, its movement through space and the curtains that define its immediate space, making the transit and the transient the material essence of the work.

Steegmann’s work spans various media and oscillates between subtle, poetic but nevertheless raw experimentations. Although mainly conceptually informed, Steegmann work displays a strong concern with the existence and features of concrete objects: Steegmann activates the abstract language as a thought-generating principle and employs unstable meaning and uncorporeal constructions as a way to address issues concerning language, body, material existence and sense production.

Daniel Steegmann Mangrané (Barcelona, 1977) has recently made the solo shows: Akademie der Kunste, Berlin; Duna económica / Maqueta sin calidad, Halfhouse, Barcelona; FOUR WALLS, Mendes Wood, São Paulo; Espaço Cultural Municipal Sérgio Porto, Rio de Janeiro; Equal (cut), Ateliê 397, São Paulo; Fundació La Caixa, Lleida.

His work has been also featured at the grup shows 30ª São Paulo Biennial, The Imminence of Poetics, São Paulo; Yemanjá Claus, Diana Stigter galerie, Amsterdam; Pindorama Suit, Rongwrong, Amsterdam; Belvedere, Estrany ∙ De la Mota, Barcelona; Espai d’Art Contemporani de Castelló, Castelló; Forgotten Bar Project, Galerie im Riegerungsviertel, Berlin; Miragem (Sempre à vista), Mendes Wood, São Paulo.

Upcoming shows include Centro de Arte 2 de Mayo, Madrid; Museo Experimental el Eco, Mexico DF; Werkleitz 2013, Halle; or Panorama 33, Museu de Arte Moderna, São Paulo.

Besides his artistic practice Daniel Steegmann Mangrané runs the experimental school Universidade de Verão at Capacete, Rio de Janeiro.

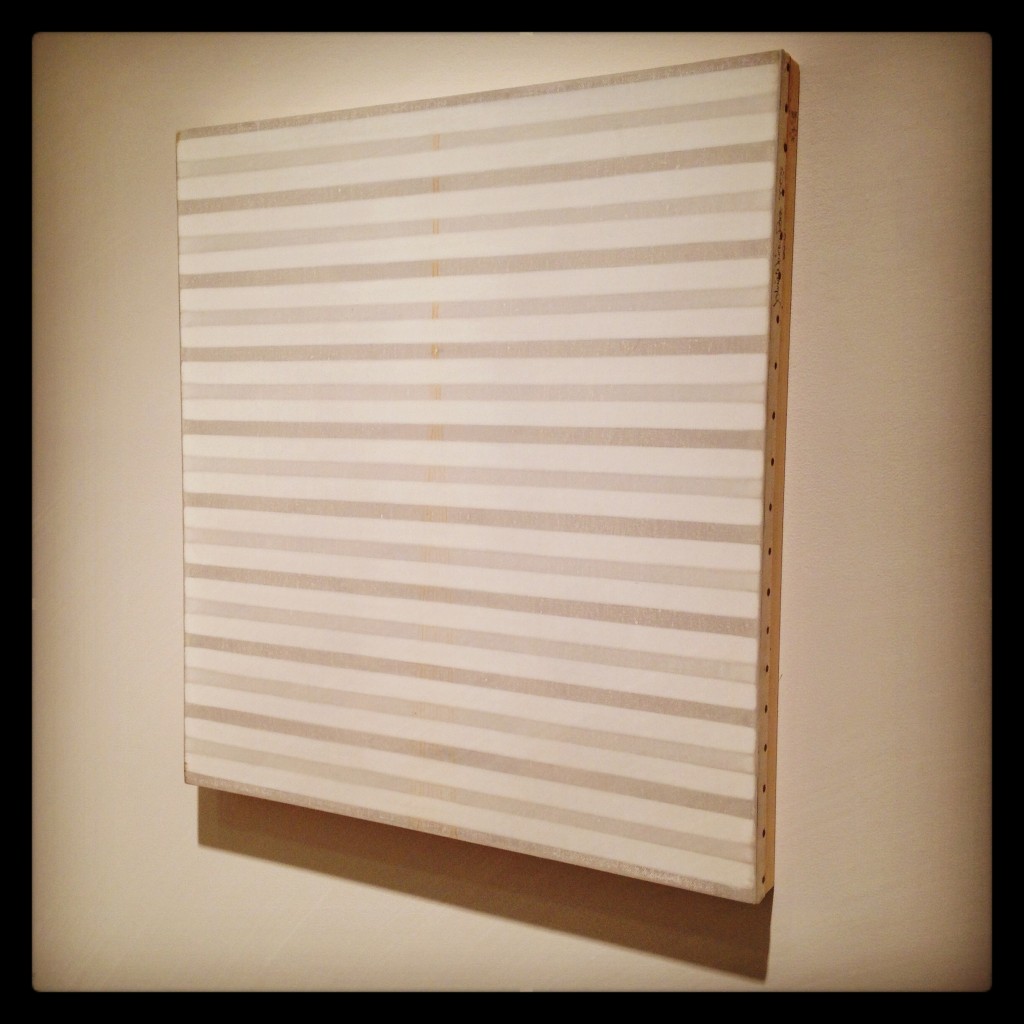

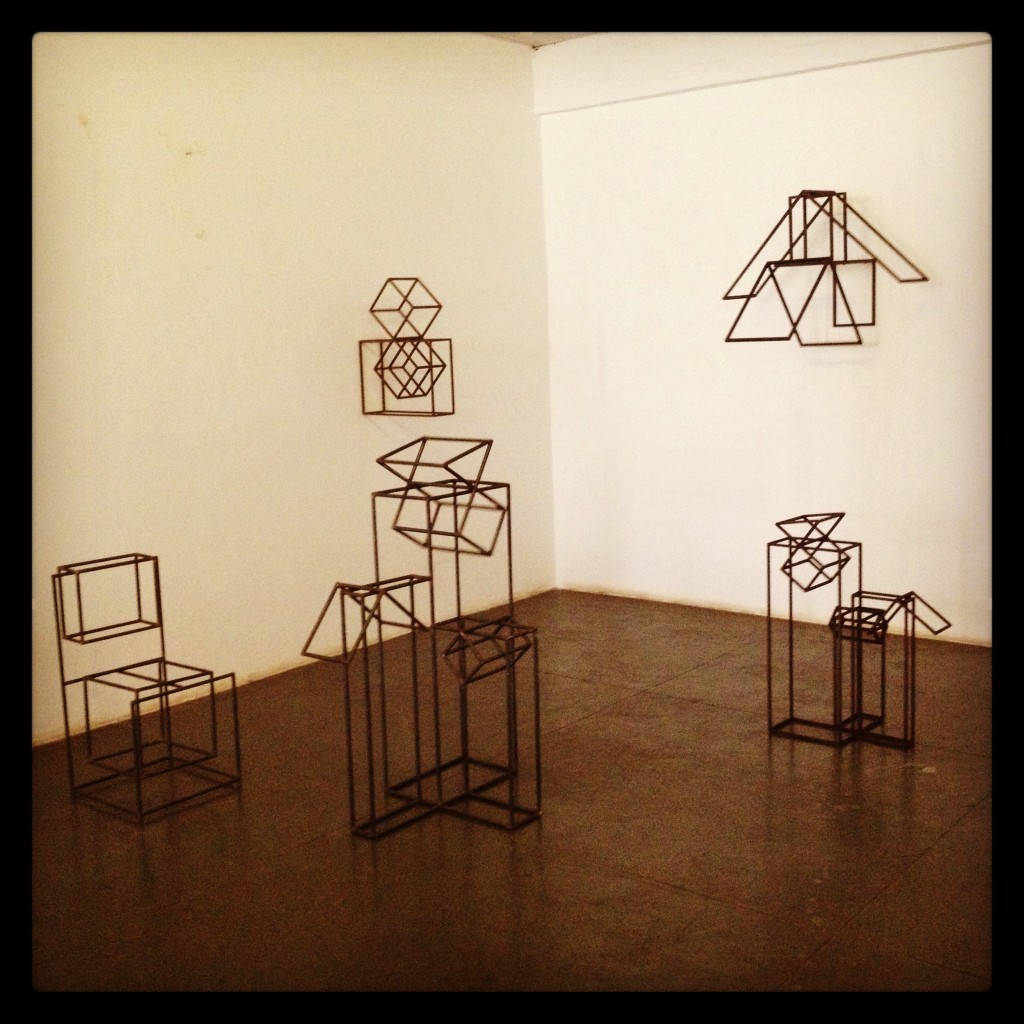

Concrete Continuity by David Ebony

How do new generations of artists absorb the art of the past? “Concrete Remains: Postwar and Contemporary Art from Brazil,” a compact show on view at Chelsea’s Tierney Gardarin Gallery (formerly Cristin Tierney), through June 22, is, in one sense, an exploration of this question. It also encapsulates an important area of Latin American art, shedding new light on the ongoing preoccupation of 21st-century Brazilian artists with their nation’s major contribution to 20th-century art: Concrete and Neo-Concrete art.

An austere form of geometric abstraction influenced by European works, especially those by the Swiss artist Max Bill, Concrete art was centered in São Paulo in the 1930s and ’40s. Launched in Rio de Janeiro, the Neo-Concrete movement, which flourished in the 1950s and ’60s, was more open and fluid, encompassing a wide variety of expression as well as mediums, including film and performance.

Organized by São Paulo-based curator Jacopo Crivelli Visconti, “Concrete Remains” contains some classic examples of Concrete works by Geraldo de Barros, including several of his influential “Fotoforma” series of abstract photos (1949-50) featuring overlapping black and white rectangles. “The artists of the Concrete movement had a utopian vision,” Visconti told A.i.A. in a recent interview. “It was a relatively stable time for Brazil, economically and politically. The Neo-Concrete movement, by contrast, evolved during a more tumultuous period. These artists’ works are more international in scope and appeal, and that’s why today they are shown extensively and are better known outside Brazil. Concrete art from Brazil, on the other hand, is only now being recognized abroad.”

Most prevalent in the exhibition are strong Neo-Concrete pieces by artists such as Amilcar de Castro, Hélio Oiticica, Sergio Camargo and Lygia Clark, whose metal construction with movable parts, Pocket Bicho (1966), is one of the show’s highlights. Juxtaposed against these familiar pieces are representative works by younger artists, such as Iran do Espírito Santo, whose precisionist carbon paper series of drawings, “Pro Labore” (2008), closely correspond to de Barros’s “Fotoformas.” Fernanda Gomes’s spare objects, featuring white paint on found wood, also find a kinship to painted white monochrome sculptures by Camargo, such as his totemlike wood piece from the early 1980s on view here.

Recent works by Jac Leirner, including her meticulous grid watercolor compositions and modular wood floor sculptures, similarly relate to Clark’s sculpture. “You can see an emphasis on the act of cutting and folding in both artists’ works,” Visconti commented. “Clark had a great interest in psychiatry, and her modular sculptures were meant to be rearranged by the viewer, in an effort to engage the audience in physical as well as mental ways. Of course, the gallery visitor cannot pick up and reconfigure one of Leirner’s new modular sculptures, but the suggestion and possibility of that action are clearly in play.”

A site-specific light-projection piece by Spanish-born Brazilian artist Daniel Steegmann Mangrané, titled with the symbol ^, demonstrates the range of possibilities young artists see in the Neo-Concrete esthetic. In this theatrical work, installed in the gallery entranceway, a triangular beam of light, emanating from a slide projector mounted on a waist-high stand, illuminates a triangular patch of gold-leaf flakes that has been fixed to the wall. Visitors walking into the main gallery block the light and create air movement, which then causes the gold triangle to flicker, as if heralding their passage into a new space.

JC/LA/CA #6

L&M Arts is pleased to present Neo Povera, a group show that explores the contemporary legacy of Arte Povera and the politics of material. This exhibition offers a selection of recent works united by a common conceptual approach to re-examining the formal constraints of artistic practice brought on by the commercialization of art and ideas. Continuing a radial dialogue that challenged the traditional trajectory of acceptable art, this show explores new materials and methodologies that have evolved in the almost fifty years since the term was first coined.

Emerging in the late 1960s, Arte Povera, literally poor art, described a generation of artists committed to exploring the aesthetics of ephemeral and accessible materials while working outside of a ferociously consuming market in an effort to dissolve boundaries between an elite art and a collective experience. In “Notes For a Guerrilla War”, the manifesto that outlined the intentions of the original movement, Germano Celant wrote:

“Over there is a complex art, over here a poor art, committed to contingency, to events, to the non-historical, to the present… to an anthropological viewpoint, to the ‘real’ man, and to the hope (in fact now the certainty) of being able to shake entirely free of every visual discourse that presents itself as univocal and consistent. Consistency is a dogma that has to be transgressed, and the univocal belongs to the individual and not to ‘his’ images and products.”

By nature, this movement is neither time specific nor rooted in the particular conditions of its day. Rather, these are sentiments that can be applied to the desire to create objects of simple and intrinsic value, free of pomp and circumstance. It reminds us that we should notallow history to confine art to its predetermined conclusions nor reductively categorize works in an imposed lineage. Instead, we are called to look at the works as the assemblage of our surroundings, rooted in the honest structure of an artist’s chosen materials.

In the time since its inception, the increased momentum of the market and the changes in our everyday functions due to technological advancements (as well as shifts in household behavior and manufacturing) have created new source material to examine this increasingly relevant sentiment. Items such as plastic, which has taken on a intensified role in our daily life since the tubular neon works of Mario Merz, are featured in Karla Black’s ethereal cellophane sculpture, Spared The Sight, 2012 and Tom Driscoll’s Flip, 2013 and Bulkhead, 2005. The latter reimagines the structure of machinery by swamping cold metal parts from appliances at the underwater research laboratory in Point Loma where he worked as a night janitor and industrial packaging materials used to protect and display consumer products for buoyant, animated versions made from colorful resin mixtures. The discourse concerning found objects in art, forwarded by artists such as Jannis Kounellis, is readdressed in works including Virginia Overton’s Untitled (Sandbag), 2013, comprised of wood, rope, and, accordingly, a sandbag.

In addition, a diverse array of materials will be represented, including Anicka Yi’s Untitled, 2013, a wall work made from soap, a large sculpture from Tara Donovan’s mylar experiments, and a series of porcelain cast styrofoam forms by Patrick Meagher. This exhibition will make use of the gallery’s sizable garden area to include a site-specific sculpture, Andy Ralph’s Manifold Destiny, 2013, that can be seen from Venice Boulevard, as well as Marianne Vitale’s Standard Crossing (1), 2013, an erect, repurposed railroad frog. In late June, Aki Sasamoto will perform one of her eponymous ‘lecture’ works based on the concept of Neo Povera. Sasamoto’s sculpture Clear Idea Bubbles, 2013, a series of plastic recycling bags that have been on display since the opening of the exhibition, will be activated with the notes, drawings, and written gestures from her lesson.

Neo Povera is curated by Harmony Murphy and includes works by Ana Bidart, Karla Black, Jed Caesar, Joshua Callaghan, Tara Donovan, Tom Driscoll, Brendan Fowler, Luca Frei, Johannes Girardoni, Liz Glynn, Jiri Kovanda, Maya Lin, Erik Lindman, Patrick Meagher, Virginia Overton, Ester Partegas, GT Pellizzi, Andy Ralph, Cordy Ryman, Aki Sasamoto, Marianne Vitale, Heidi Voet, Anicka Yi and Anton Zolotov.

GALLERY INFORMATION:

L&M Arts, Los Angeles, 660 South Venice Boulevard, Venice, CA, 90291. Tuesday – Saturday, 10:00 – 5:30 and by appointment. For additional information, please contact L&M Arts at: +1.310.821.6400 or visit our website: www.lmgallery.com.

TIMELINE #6 (RIO)

PAULO PASTA LIVRO BARLÉU NA MILLAN

SÁBADO TRAVESSIAS MARÉ

Christie’s Rakes In $495 Million — the Highest Total for Any Art Auction, Ever

Tonight, only four of the 70 lots offered failed to find buyers for a near-perfect buy-in rate by lot and value of six percent. The tally crushed presale expectations of $288.9-401.4 million, though that spread does not reflect the buyer’s premium included in the overall result. Head-turning statistics included the fact that 59 of the 66 lots sold hurdled the million-dollar mark. Of those, 23 made over $5 million. More incredibly, nine topped $10 million.

A dozen artist records were set, led by the ravishing cover lot, Jackson Pollock’s small but mighty “Number 19, 1948,” a stunning drip painting in oil and enamel on paper mounted on canvas, which sold to an anonymous telephone bidder for a whopping $58,363,750 (est. $25-35 million). The epic bidding battle for the Pollock began at $18 million and quickly escalated at million-dollar increments to a point where three bidders were still competing at the $40 million plus mark, including dealers Jose Mugrabi and Dominique Levy.

Described in the catalogue as the property of an American foundation, the shimmering painting, which last sold at auction at Christie’s New York in May 1993 for $2,422,500, subsequently entered the collection of Potomac, Maryland billionaire Mitchell Rales and his Glenstone Foundation. The price obliterated the mark set by “Number 4,” a 1951 canvas that made $40,402,500 at Sotheby’s New York last November.

It couldn’t have hurt that critic Clement Greenberg, reviewing the Pollock exhibition atBetty Parsons Gallery in January 1949, singled out “Number 19,” saying it “seemed more than enough to justify the claim that Pollock is one of the major painters of our time.”

Edvard Munch’s “The Scream” may have sold for $120 million at Sotheby’s last year, but still, the fact that an AbEx work on paper could sell for $50-plus million is an extraordinary milestone. The question easily arises, what the heck happened between Sotheby’s strong but sober $293.5-million sale on Tuesday and Christie’s fantastic results on Wednesday?

“We had two single-owner collections,” said Marc Porter, chairman of Christie’s America and global head of private sales, shortly after the fireworks ended, “and we had great single works, so we had the culmination of both elements.” Porter was referring in part works from the Armandand Celeste Bartos collection, which together made $30.2 million, and a trove of paintings from the estate of crooner Andy Williams, which brought $46 million.

Singular artworks across a broad spectrum of time and styles went through the roof, including the huge and funky Jean-Michel Basquiat painting, “Dustheads” (1982), executed in acrylic, oilstick, spray enamel, and metallic paint on canvas, which sold to another anonymous telephone bidder for a record $48,843,750 (est. $25-35 million). The Wild West bidding for this Basquiat, known in the trade as a classic “pissing contest,” saw two mega-rich individuals duke it out in a cat-and-mouse bidding game that started at $20 million. It left the previous Basquiat record, set at Christie’s New York last November when “Untitled” (1981) made $26,402,500, in the dust.

Semi-retired art dealer Annina Nosei, who harbored Basquiat in her basement space on Prince Street at the dawn of the 80s, and sold the painting for under $5,000 to Maggie Bult (at least as she recalled it), attended the sale. Now a senior champion ballroom dancer, Nosei said, “I wish I kept it. I never come to auctions, but I did for this painting. It is a masterpiece, both for its intrinsic size, the painterly language, and the structure itself. I’m without words.”

The record Basquiat came to market with a third-party guarantee, taking the risk off Christie’s and assuring that the anonymous speculator made a fortune on the transaction.

Another Basquiat, this one a work on paper, “Furious Man,” also made a huge sum, selling toJerry Lauren for $5,723,750 (est. $1-1.5 million). It last sold at Sotheby’s New York in May 2001 for $302,750. Here, it was one of the standout pieces from the Andy Williams collection.

“I’m a folk art collector,” said Lauren, as he exited the heaving, standing-room-only salesroom, “and I can identify with this because it’s American street folk art.” Lauren, who bid from a last row seat in the salesroom, is the creative head of men’s fashion at Ralph Lauren (no relation). He explained that he collects Bill Traylor, a storied folk artist, as well as American weathervanes, stoneware, and “very rare Americana.” Needless to say, it is his first Basquiat.

Another record went to the remarkable Roy Lichtenstein painting from 1963, “Woman With Flowered Hat,” a pastiche-slash-Pop-appropriation of a Picasso painting that sold to London-based jewelry magnate Laurence Graff for $56,123,750 (est. on request in the region of $30-40 million).

“I got a masterpiece and I’m very lucky, because it’s one of four ladies Lichtenstein did and this is the best example,” said a still-elated Graff, buttonholed outside Christie’s Rockefeller Center headquarters. “There are fewer and fewer masterpieces coming to market and I love this painting.” Graff also cracked that it is just weeks away from his birthday, “so it’s going to be my birthday present.”

The painting mashed the previous high set a year ago at Sotheby’s New York when Lichtenstein’s “Sleeping Girl” (1964) sold for $44,882,500.

The art market tonight appeared giddily bulletproof as London-imported auctioneer Jussi Pylkannen confidently extracted multi-million-dollar bids from the room and banks of telephone bidders. In this super-charged atmosphere, certainly reminiscent of past bubble moments, uncanny prices popped like vintage champagne corks. The top-class and widely exhibited Philip Guston AbEx-era painting, “To Fellini” (1958), which was chased by at least five bidders, soared to a record $25,883,750 (est. $8-12 million). Piero Manzoni‘s folded abstraction, “Achrome” (1958) made a huge $14,123,750 (est. $6-9 million).

In fact, no matter where you turned, it seemed as if the spigot was left on. Another AbEx icon,Mark Rothko and his darkly luminous “Untitled (Black on Maroon),” also dated from 1958, sold to New York dealer Dominque Levy for $27,003,750 (est. $15-20 million). (Levy also bought Willem de Kooning‘s sexy, 28-by-20-inch “Woman (Blue Eyes),” from 1953, for $19,163,750 [est. $12-17 million]).

Gerhard Richter’s richly textured and colorful “Abstraktes bild, Dunkel (613-12)” (1986) sold to a telephone bidder for $21,963,750 (est. $14-18 million). The anonymous seller bought it fromSperone Westwater in New York during one of Richter’s first exhibitions in the U.S. in 1987. At the time, the work was well under $100,000.

But the standout evening wasn’t all about the past either, as evidenced by Julie Mehretu’s mural-like architectural landscape, “Retopistics: A Renegade Excation” (2001), which sold for a record $4,603,750 (est. $1.4-1.8 million).

“This is a landmark moment for us,” said Koji Inoue, Christie’s head of the evening sale in an after-sale remark. “It was a win-win across all categories.”

The contemporary action closes out the season Thursday evening at Phillips.

To see highlights from Christie’s record-setting sale, click on the slideshow.