He played all the non classic Brazilian tunes you might not think of, when it comes to Brazilian music. not even one touch of Samba. instead, I was shaking my head to some raw bass lines with fuzzy psychedelic guitars, and of course the oh so sexy Portuguese language.

One of the things I like about NYC (and maybe the U.S. in general) is the richness and diversity of the art scene, specially when it comes to music and its roots. so many DJ’s, such a long history of music making, and the abundant of vinyl that was pressed (and still being pressed) and collected thru time, just makes this place a heaven to any one who consume music. you could enjoy a night of Brazilian soul, or some west African funk, or maybe some 60’s Boogaloo? or perhaps you are into 60 Psych rock played only from 45’s? or maybe you wanna get specific on that organ sound? I bet you could find the right gig for you happening somewhere. that’s why I love America, beside the fact that suddenly, I can charge all my U.S. electronic devices I bought in the past and used in Israel, without any adapter. yes, that’s a very convenient reason.

anyways,

back to Greg.

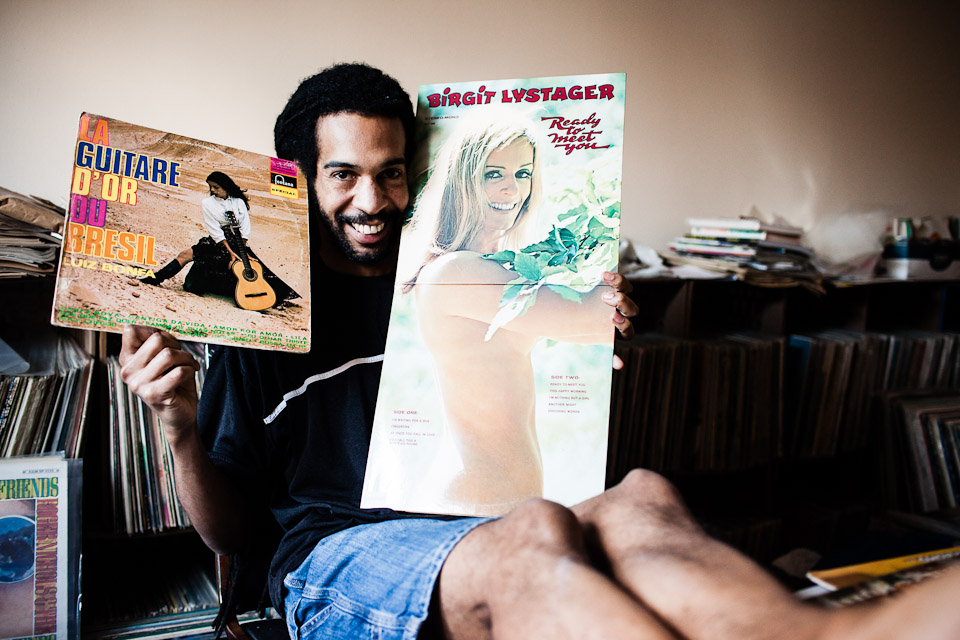

I biked to his house in the Queens, in a cloudy and windy afternoon. the day started out with a beautiful sun, and I thought that I would have the perfect light coming thru his windows. but, god had some other plans, and I arrived to his place in a semi frozen condition and cloudy skies.

A medium sized apartment, living room, piles of records on the floor, a hidden kitchen, more records on some racks in the living room, bedroom with a double bed, more records everywhere, a walk in storage room, filled with records and other collectible stuff (like the whole Wax Poetics magazine catalog).

I’m still in the bedroom, trying to find a place to put my feet without stepping on a record. a stereo machine with a record player just beside the bed. you gotta be fast to flip that record when needed.

records everywhere! the first thing that came to my mind was, is there any order in this setup? I popped this question to Greg, and he immediately started to explain me about the logic. this is here, this is there, but after a while he got confused. ohh, maybe this is that, and that is this. The mad scientist always has his own order in the great chaos. that was also the case with Greg.

so here it is, Greg Caz, 37, Queens, NY. The mad scientist of Brazilian beats (and other stuff of course).

Hit that player button to listen to Greg’s compilation “Baile Funk 2 Agora é Moda”

http://www.divshare.com/flash/playlist?myId=6452470-cc5

Q: What prompted you to start collecting?

A: Since the day I was born, I’ve been around people with sizable record collections, starting with my dad, uncles, cousins…it wasn’t till later I realized there was any other way to be!

Q: What age did you start?

A: At conception….literally!

Q: What was your first album?

A: First I remember, around age 3, was “Abbey Road.” The “Wattstax” concert soundtrack was a really early one too.

Q: Initial interest in music? did you get influence from your family?

A: Again, my dad playing jazz and Brazilian records on his powerful 70’s Hi-Fi system all the time. Also, my hippie soul brother uncle Alix (RIP) giving me rock and soul records, starting with the ones I mentioned above.

Q: Any particular musical instruments?

A: I was obsessed with two drummers in my childhood: Art Blakey and Ringo Starr. So for a while I took lessons cause I wanted to be them.

Q: Why music?

A: What else is there? ![]()

Q: Why vinyl?

A: Cause that was always the format, holding the covers, going through my dad’s and uncles’ shelves, looking at them and feeling like these big beautiful things held the secrets of the universe….which they did. And the feeling growing up of walking into a RECORD store and seeing them all displayed, shiny and new, well….only sex is comparable, and maybe not even!! (now I understand the proximity of the stereo to the bed. E.P.)

Q: How many LPs?

A: I’d say around 10,000 or so, but it fluctuates….

Q: 45s?

A: Far less, but I’ve got a few goodies…

Q: You are an expert in Brazilian Beats. How did you start with it? When?

A: See above. Again, I grew up around people like my dad for whom people like Elis Regina and Chico Buarque and Milton Nascimento were just common knowledge. All my life, if I saw somebody with records like those, I knew this person understood the finer things in music and life.

Q: Do you go to Brazil to get inspiration? Collect records?

A: Both, and see my friends, and hang out with beautiful girls whose language (Portuguese) I speak beyond fluently.

Q: Do you travel to find records? where? how often?

A: I’m ALWAYS on the lookout for records, no matter where I am….especially anytime I travel somewhere. “Hmmm….what can I find here that I can’t find near me?”

Q: How do you organize the collection?

A: Roughly, alphabetically according to genre, although not really, since different gigs of different genres on different nights mean that I end up with piles and stacks everywhere, although I’m pretty good at finding any given record when needed….most of the time.

Q: Have you ever battled for a rare record? what happened?

A: Not really…..maybe times in Brazil or somewhere when I had to plead, negotiate, cajole, etc. But “battle”? Maybe not. I used to be an expert at eBay sniping, though…..

Q: Tell me a crazy story over a certain record

A: A few years ago I bot an original copy of Can’s “Ege Bamyasi” at the WFMU fair in New York. Eight bucks, great deal! And when I got home and pulled it out of the sleeve, a bunch of bags of coke fell out ![]()

Q: What’s your partners’ reaction to this obsession?

A: Intrigued, amused, fascinated….but I would say that relationships are HELL on record collections. Women usually have a threshold of tolerance for this “beautiful sickness” that no matter what they say initially, they eventually pass and then you have to get rid of them to make space for their shoes, ha ha ha…..

Q: Any numbers on that price tag?

A: I have ones worth at least several hundred that I managed to get without actually having to spend that much. I never spent more than about a hundred or so, several times, nothing too outrageous.

Q: What part of your monthly budget do you spend on records?

A: Historically, way too much. Lately, not a lot, it’s been a bit tight and rent comes first, so I’ve been really into dollar records these days!

Q: Names of stores, trade shows, flea markets, thrift shops? record conventions?

A: Not too many left these days unfortunately! Academy Records (where I worked for several years), Tompkins Square Books And Records (RIP), Chelsea Flea Market (RIP), Second Coming Records (RIP), Kim’s on St. Marks (RIP) (this is getting depressing), WFMU Record Fair (once a year where it used to be twice), Dusty Groove, my guys Carlinhos and Tony Hits in São Paulo, Notting Hill Record Exchange in London, your mom’s record collection ![]()

Q: List 5 rarest 45’s or LPs

A: I don’t know what counts as “rare” anymore these days. Got a great Hungarian funk-rock record by a band named Skorpio recently. Wilson Simonal’s Mexico-only “Mexico 70″ LP. “Zeca Do Trombone & Roberto Sax” (1976) is pretty freaking rare, as is “Edson Frederico e a Transa” (1975). Eugene McDaniels’ “Headless Heroes Of The Apocalypse” (1971). All these are “rare,” but “rarest”? Music means so much more to me than whatever the going eBay cost is…..

Q: If a record label would ask you for the perfect compilation of your favorite genre. What would be the 10 top songs? Would you like to publish it on my blog?

A: Impossible. One mix could never capture it…..

Q: What do you do for a living?

A: Lately, mostly DJing (not easy, I’m telling you!!). I’ve been a music retail buyer, journalist, a number of things, but these days just focus on the DJ work.

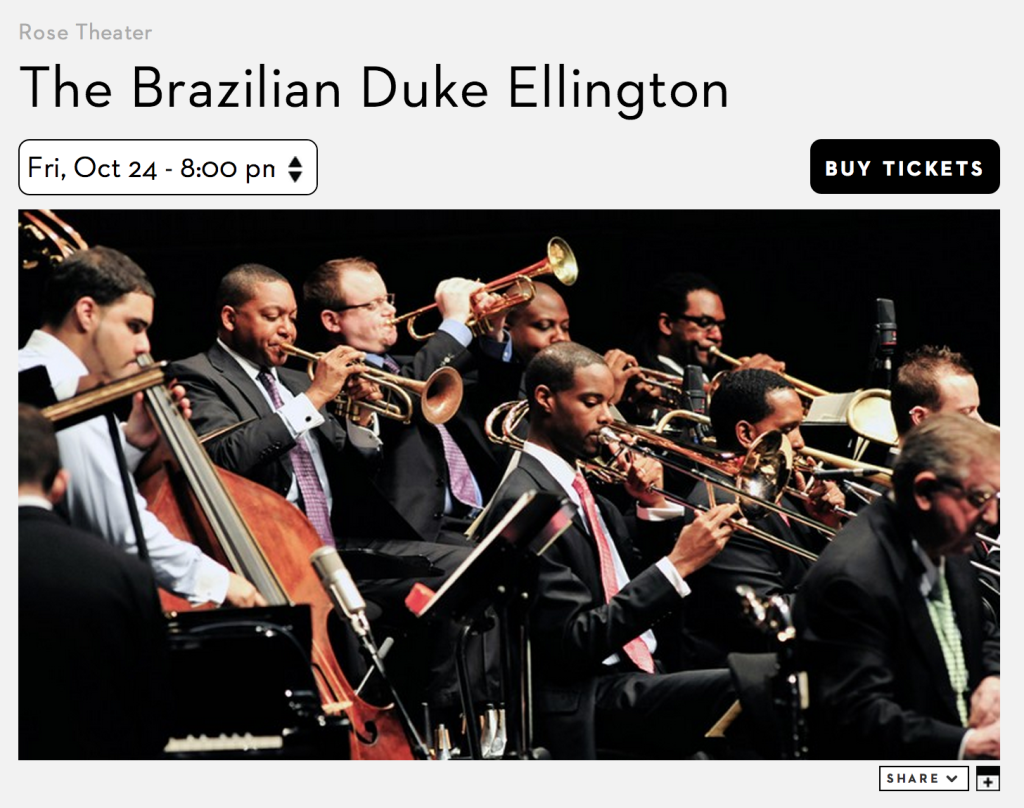

Q: You have a Brazilian beat night. Where & when?

A: At Black Betty, every Sunday night, 366 Metropolitan Ave, Williamsburg. Also every Wednesday at Nublu, 62 Ave. C.

Q: So, you make it for a living. what do you listen to when you’re home? Just for joy. Is it different from the music you play on gigs?

A: YES, I listen to music at home, A LOT, and most of it is stuff that drunk partygoers in a club at night could never ever ever understand, sadly…..even if you played it to them in the daytime!!!!

Q: is there an album / 45 that you are trying to find, unsuccessfully?

A: My list is ongoing, and I know them when I see them. I cast my net wide, so specifics are kind of besides the point. I’d like to find a huge stash of cheap original UK 70s pressings on the Vertigo label, for one…..

Q: Do you have any favorite album cover?

A: Listen man, you have to understand that in dealing with people like me, who have long ago crossed the limit that “normal” people stop at in relation to the absorption and understanding of music, questions like “favorite album/artist/genre/label/cover/etc” are utter BULLSHIT. People less consumed with music can easily give you those answers, but me (and those of my tribe) simply cannot, and that’s just the way it is……

Q: Any particular painters/ photographers/ illustrators?

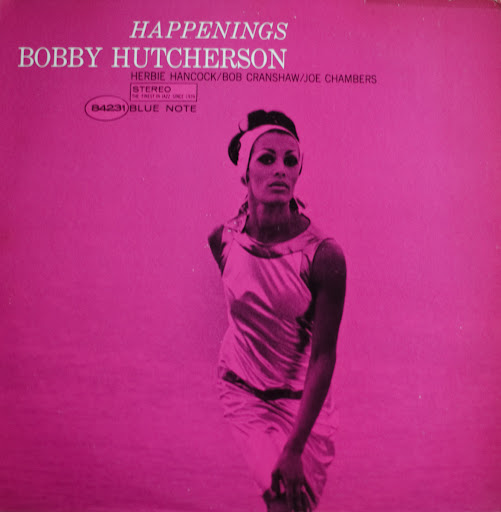

A: Here’s one I can think of: Reid Miles, who did the classic Blue Note covers and designs….

Q: Dirtiest, sexiest , filthiest album cover you know or own?

A: This one makes me laugh. Big Black – “Songs About Fucking” It’s hilarious! Don’t even care so much for the record, just love that cover. I always thought “Thank You Baby” by The Stylistics has a really tastefully sexy cover shot by Si Chi Ko.

Well folks, I hope you learned a thing or two. I know I did. first of, Greg is a funny guy, and honest, and has a pretty “in your face” attitude. I like it and appreciate it. sorry for the bullshit questions, and thanks for the straight answers.

here are some of the stuff that was playing while we were shooting photos, straight from the Caz academy for advanced non-bullshit music. read & learn:

MARCOS VALLE “Garra” (Odeon/EMI, 1971)

MARCOS VALLE “Garra” (Odeon/EMI, 1971)

The best album by one of my all-time favorite artists, and sheer pop perfection. The songwriting, arrangements, production values, the whole flow of it….sheer delight. Shades of Jimmy Webb, Burt Bacharach, Paul McCartney, soul music, film soundtrack scores and (needless to say) the whole Jobim/bossa heritage he so proudly carries. The title track by itself is two minutes and 58 seconds of heaven I will NEVER tire of hearing all the time.

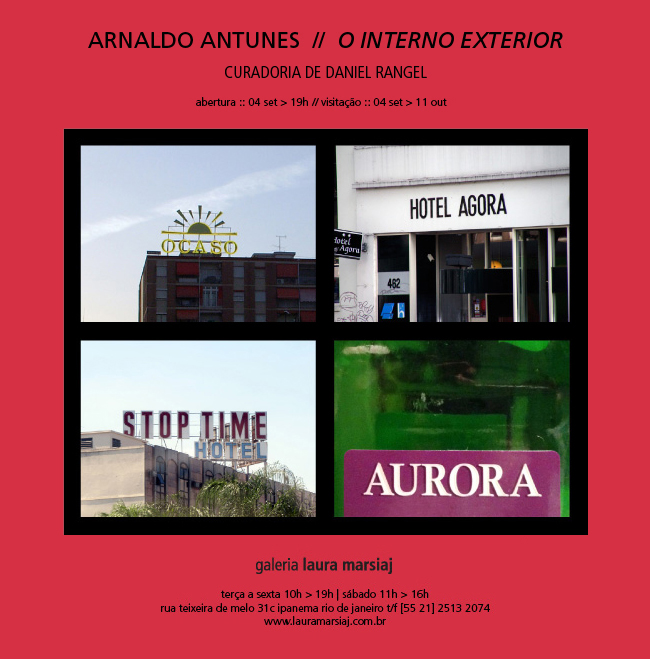

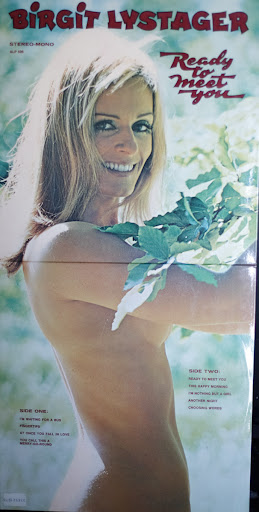

BIRGIT LYSTAGER “Ready To Meet You” (Artist, 1970)

A Danish pop gem that sounds like what would happen if Astrud Gilberto, Karen Carpenter and Joni Mitchell were combined and put in the studio with Burt Bacharach (him again!). Intelligent, complex songs, breathtaking arrangements, accompaniment from some of Copenhagen’s finest jazz musicians, and if all that weren’t enough, the lovely Birgit goes the extra mile and poses nude on the beautiful gatefold sleeve! This one was incredibly difficult to get a hold of, as you can imagine…..

EARL COLEMAN & THE LATIN LOVE-IN (Worthy, 1967)

EARL COLEMAN & THE LATIN LOVE-IN (Worthy, 1967)

Great Latin soul/boogaloo record out of Brooklyn, a tough local band of young Latino players led by an African-American pianist. Super-rare and well worth the search. Lots of fun, as titles like “Sex Drive In D Major” and “Hippy Heaven” suggest!

and I would add… is that Karem Abdoul Jabaar on the cover? (E)

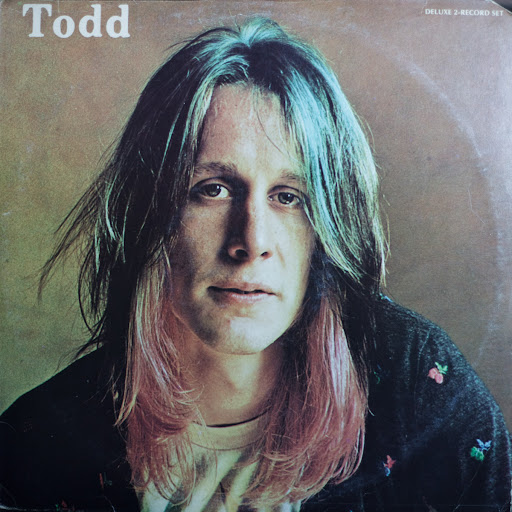

TODD RUNDGREN “Todd” (Bearsville, 1974)

Endlessly fascinating double-LP opus from one of my enduring heroes, the great Todd! Recorded over the summer of 1973 (but only released six months later), this brilliant album goes from electronic experiments far ahead of their time to pounding rockers to perfect pop to spacy philosophical ruminations to Todd’s trademark impish sense of humor. Coming off several huge radio hits with a mainstream audience expecting more of same, this (and its immediate predecessor “A Wizard, A True Star,” perhaps even more of a masterpiece) was too brave and individualistic by far, and Mr. Rundgren forfeited his chance to be a bigger superstar than contemporaries like Bruce Springsteen or Elton John. To compensate, though, his enormous (and still growing!) body of work is a vast garden of delights that is still being discovered and influencing bands like Daft Punk and Hot Chip among many others.

CRAVO & CANELA “Preço De Cada Um” (Pesquisa, 1977)

CRAVO & CANELA “Preço De Cada Um” (Pesquisa, 1977)

One of the most mysteriously rare albums in the Brazilian collecting game, and a warm, lovely, grooving example of MPB in the mid-to-late 70s, before the 80s ruined everything. Solid four-piece band fronted by two lovely female vocalists, great material ranging from vintage Noel Rosa to latter-day originals by special guest Sivuca, all delivered with expertise and conviction. Special thanks to the Japanese for FINALLY making this record available again, however briefly!

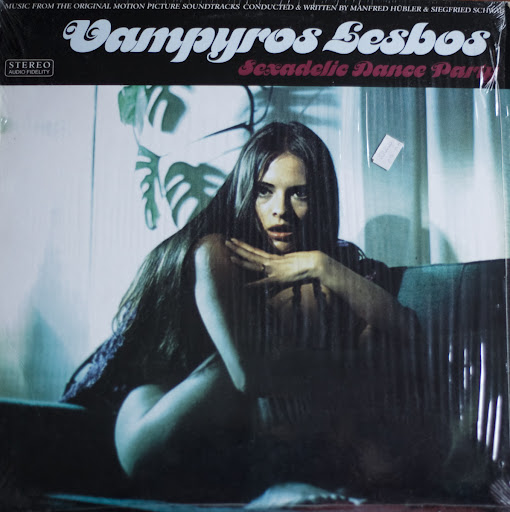

VAMPYROS LESBOS Soundtrack (Motel Records)

Late 60s German soundtrack from a series of soft-porn films starring the late Soledad Miranda, alternately creepy, groovy, Gothic, funky, and definitely mysterious. This reissue is wonderfully annotated with a cool poster, and the hole in the center of the vinyl is placed in a very, ummm….”strategic” place (I’ll say no more!!!).

BOBBY HUTCHERSON “Happenings” (Blue Note, 1966)

Hard to pick a favorite Hutch LP, and in fact there are several I like even better than this one, but it has a great cover. But having said that, this is a PHENOMENALLY great album and recognized as one of his great classics. Great quartet session with Herbie Hancock, beautifully turned out and with great performances from all involved. Includes the first-ever cover version of the Hancock modern jazz standard “Maiden Voyage.”

*** If you wanna participate in this project, please email me at: dustandgrooves@gmail.com

many more to come…

Eilon