Documentário Sergio Camargo

encontros no Parque Lage

Arto Lindsay na Progetti

Galeria Nara Roesler na ZONAmaco 2010

A Galeria Nara Roesler tem o prazer de participar pelo 7o ano consecutivo da ZONAmaco, a feira de arte contemporânea do México, de 14 a 18 de abril.

Stand: G207

Dias e horários: 14.04 – 13h às 17h [somente para grupos de museus, imprensa e com convite especial] — 17h>22h [público em geral]

15/16/17.04 – qui/sex/sab 17h>22h

18.04 – dom 12h>20h

Centro Banamex (Sala D) – Av. Conscripto 311, Lomas de Sotelo México D.F.

Centro Banamex: (52) 55 5268 2000

Zsona Maco: (52) 55 5280 6073

Informações: info@nararoesler.com.br

Roteiro para visitação – Carlito Carvalhosa

Event Horizon – Antony Gormley

peguei la no site http://eventhorizonnewyork.org/

From March 26 through August 15, 2010, The Madison Square Park Conservancy will present Antony Gormley’s Event Horizon, a landmark public art exhibition, as part of Mad. Sq. Art 2010.

In Event Horizon, thirty-one life-size body forms of the artist cast in iron and fiberglass will inhabit the pathways and sidewalks of historic Madison Square Park, as well as the rooftops of the many architectural treasures that populate New York’s vibrant Flatiron District. Event Horizon marks Gormley’s United States public art debut — a milestone for an artist whose work has garnered worldwide acclaim over the past 25 years.

“I’m thrilled to be working with New York: people and place,” says artist Antony Gormley. “I don’t know what is going to happen, what it will look and feel like, but I want to play with the city and people’s perceptions. My intention is to get the sculptures as close to the edge of the buildings as possible. The field of the installation should have no defining boundary. The gaze is the principle dynamic of the work; the idea of looking and finding, or looking and seeking, and in the process perhaps re-assessing your own position in the world. So in encountering these peripheral things, perhaps one becomes aware of one’s status of embedment.”

Antony Gormley originally created Event Horizon for London’s Hayward Gallery as part of the Blind Light exhibition in 2007. The sculptures were installed on bridges, rooftops and streets along the South Bank of London’s Thames River. In this New York incarnation, Antony Gormley has adapted this exciting project to Manhattan’s unique and awe-inspiring skyline.

In an age in which over 50% of the human population of the planet lives in cities, this installation in New York (the original and prime example of urban high-rise living) questions how this built world relates to an inherited earth.

Isolated against the sky these dark figures look out into space at large asking: where does the humanity fit in the scheme of things?

The ambition is to make people visually aware of their own surroundings and the skyline above their heads.

In observing the works dispersed over the city viewers will discover that they are the centre of a concentrated field of silent witnesses; they are surrounded by art that is looking out at space and perhaps also at them. In that time the flow of daily life is momentarily stilled.

Within the condensed environment of Manhattan’s topography the level of tension between the palpable, the perceivable and the imaginable is heightened because of the density and scale of the buildings.

In London I took great enjoyment from the encounter with individuals or groups of people pointing at the horizon in the manner of a classical sculptural group. This transfer of the stillness of sculpture to the stillness of an observer is exciting to me: reflexivity becoming shared.

There will be a strong secondary point of view from high windows around Madison Square Park, so more than in any other installation of Event Horizon, the occupants of the buildings will be aware of these three dimensional shadows at the edge of their field.

The level of visibility and the idea of the gaze, is the principle dynamic of the work; the idea of looking and finding, or looking and seeking, and in the process perhaps re-assessing your own position in the world.

One of the implications of Event Horizon is that people will have to entertain an uncertainty about the work’s scope: the spread and number of figures. Beyond those that you can actually see, how many more remain out of sight?

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

View photo credit

LURIXS informa:

Carlito Carvalhosa informa:

Recebi essas fotos do grande artitista plástico paulistano residente no Rio. São imagens da montagem da exposição individual Roteiro para visitação que Carlito inaugura dia 13 de abril no Palácio da Aclamação, Salvador, BA. Mais uma intervenção da pesada com a assinatura Carvalhosa. A exposição fica até 30 de junho.

Apple iPad Ad Promo Video 2010

How the Tablet Will Change the World

matéria de capa da Wired que eu peguei lá no site.

Photo: Dan Winters; tablet: Stan Musilek

Everyone who jammed into the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco on January 27, 2010, knew what they were there for: Apple CEO Steve Jobs’ introduction of a thin, always-on tablet device that would let people browse the Web, read books, send email, watch movies, and play games. It was also no surprise that the 1.5-pound iPad resembled an iPhone, right down to the single black button nestled below the bright 10-inch screen. But about an hour into the presentation, Apple showed something unexpected — something that not many people even noticed. In addition to the lean-back sorts of activities one expects from a tablet (demonstrated by Jobs while relaxing in a comfy black armchair), there was a surprising pitch for the iPad as a lean-forward device, one that runs a revamped version of Apple’s iWork productivity apps. In many ways, Jobs claimed, the iPad would be better than pricier laptops and desktops as a tool for high-end word processing and spreadsheets. If anyone missed the point, Apple’s design guru Jonathan Ive gushed in a promotional video that the iPad wasn’t just a cool new way to gobble up media — it was blazing a path to the future of computing.

The wedge-shaped cuneiform on this Assyrian tablet is actually early legalese.

Erasable slates used by schoolkids put a premium on memorization.

A paper mill employee cut, ruled, and bound reject sheets to create the legal pad.

The Apple MessagePad—and the Newton OS—almost recognized handwriting.

Star Trek introduced the PADD — Personal Access Display Device.

Even though the iPad looks like an iPhone built for the supersize inhabitants of Pandora, its ambitions are as much about shrinking our laptops as about stretching our smartphones. Yes, the iPad is designed for reading, gaming, and media consumption. But it also represents an ambitious rethinking of how we use computers. No more files and folders, physical keyboards and mouses. Instead, the iPad offers a streamlined yet powerful intuitive experience that’s psychically in tune with our mobile, attention-challenged, super-connected new century. Instant-on power. Lightning-fast multitouch response. Native applications downloaded from a single source that simplifies purchases, organizes updates, and ensures security. Apple has even developed a custom chip, the A4, that both powers the machine and helps extend its battery life to 10 hours. The iPad’s price puts it in the zone of high-end netbooks: $500 for a basic 16-gig, Wi-Fi-only model. (A version with AT&T 3G connectivity will cost $130 more, plus $30 a month for unlimited data.) But don’t call it a netbook, a category Jobs went out of his way to trash as a crummy compromise. The iPad is the first embodiment of an entirely new category, one that Jobs hopes will write the obituary for the computing paradigm that Apple itself helped develop. If Jobs has his way, before long we may be using our laptops primarily as base stations for syncing our iPads.

The fact is, the way we use computers is outmoded. The graphical user interface that’s still part of our daily existence was forged in the 1960s and ’70s, even before IBM got into the PC business. Most of the software we use today has its origins in the pre-Internet era, when storage was at a premium, machines ran thousands of times slower, and applications were sold in shrink-wrapped boxes for hundreds of dollars. With the iPad, Apple is making its play to become the center of a post-PC era. But to succeed, it will have to beat out the other familiar powerhouses that are working to define and dominate the future.

There’s a lot to love about Apple’s vision. As we start to establish the conventions made possible by advanced multitouch, we’ll perform ever more complicated tasks by rolling, tapping, and drumming our fingers on screens, like pianists tickling the ivories. The iTunes App Store model gives us a safe and easy means to get powerful programs at low prices. Rigidly enforced standards of aesthetics will ensure that the iPad remains an easy-to-navigate no-clutter zone. And since we’re obligated to link our credit cards to Apple, micropayments are built in, providing traditional media companies with at least a hope of avoiding the poorhouse.

But there’s also a lot to worry about. It’s a pain to lug around an external keyboard, which many people will require if they’re serious about banging out documents. (My brief exposure to the iPad’s onscreen keyboard wasn’t encouraging.) Apple’s system is closed in a way that the Mac (and even Windows) OS never was — all apps are cleared through Cupertino, and developers and publishers are a step removed from their users, who make transactions through the App Store.

That Apple-centric vision assures a nasty fight ahead. In particular, the iPad represents a head-butt to another bold new model for computing: Google’s Chrome OS.

In some ways, Chrome is even more radical than the iPad. Spawn of a pure Internet company, it is itself pure Internet. While Apple wants to move computing to a curated environment where everything adheres to a carefully honed interface, Google believes that the operating system should be nearly invisible. Good-bye to files, client apps, and onboard storage — Chrome OS channels users directly into the cloud, with the confidence that the Web will soon provide everything from native-quality applications to printer drivers. Google hopes that a wave of Chrome-powered netbooks set for release this fall will hasten that day, and its designers are already sketching out the next generation of Chrome OS devices, including touchscreen tablets.

Google vice president Sundar Pichai contends that having an iTunes-like app store is unnecessary, because desktop software is just about dead. “In the past 10 years, we’ve seen almost no new major native applications,” he says, ticking off the few exceptions: Skype, iTunes, Google Desktop, and the Firefox and Chrome browsers. “We are betting on the fact that all the user will need are advanced Web apps.” (Pichai acknowledges that the Web can’t currently handle powerful games but says that new technologies like Native Client and HTML5 will fix that problem.)

Though critics of Google worry about the company’s power, Chrome OS is an open source system, and the Web apps Google encourages will, unlike Apple’s, be available on any device or browser.

Apple won’t talk on the record about Google’s browser-centric approach, but Jobs did address the notion when I interviewed him about interfaces several years ago. “While we love the Web and we’re going to have the best Web browser in the world, we do not want to make our UI look like a Web page,” he said. “We think that’s wrong.” Clearly, he still thinks so. Apple favors the pristine orderliness of autocracy to the messy freedom of an open system.

While Google and Apple are each positioning themselves as pioneers of the next paradigm, Microsoft — the company that dominates the current one — has a more iterative approach. It’s taking an evolutionary path that integrates the seismic changes in the digital world into its flagship products, without any jarring leaps. Three years back, Microsoft introduced Surface, a technology that lets people use their fingers and objects to interact with table-sized displays. Later this year, the Xbox will implement a motion-tracking system called Project Natal. Chief strategy officer Craig Mundie, Redmond’s delegated seer, says it’s all part of a transition from the GUI — the graphical user interface that began with Mac and Windows — to the NUI — a natural user interface based on touch, gestures, and voice recognition.

Incremental change, however, can ultimately mean no change. A decade ago, Microsoft came up with its own vision of a tablet computer. But the company tried to have it both ways: a new category of device that ran an old style of software — specifically, a modified version of Windows. (Using Windows, computer pioneer Alan Kay says, was “a very bad idea for this kind of interaction.”) The Tablet PC, introduced in 2002, was a flop. Meanwhile, advances from Microsoft’s labs can approach bar mitzvah age before finding their way into products. Surface is the most exciting product out of Redmond in years, but the company has been shockingly timid in pushing it into the marketplace. Almost three years after it was announced, Surface is still a novelty in a few hotel lobbies and retail stores. Apple all but announced that the iPad could damage its own desktop and laptop business, but Microsoft never seems to put all its weight behind groundbreaking products — especially if success may come at the expense of its Windows and Office cash cows.

Indeed, Microsoft seems locked into producing somewhat improved versions of those programs every few years. That means a decade from now, Microsoft’s answer to the challenges from Apple and Google will be… yet another Windows upgrade. I ask Mundie whether we will see a Windows 10. “Sure, from a brand point of view,” he says. Will it resemble the Windows we know and, um, love? “Who knows?”

One thing we do know is that a heated battle is breaking out over the grave site of the GUI. While unveiling the most heralded Apple product since the iPhone, Jobs presented a powerful and compelling vision of what comes next. Now he will have to fend off some tough rivals — and tough criticism — to make that vision a reality.

Wired – iPad

Surdo_Mudo #2

Influenza? _ 09

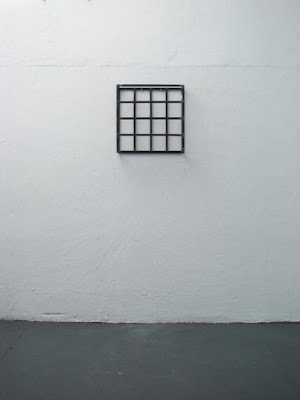

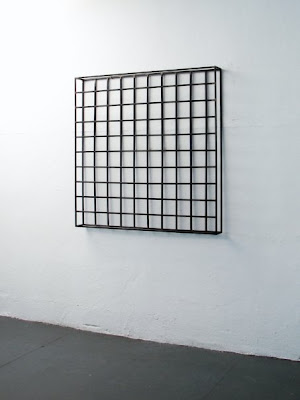

2 trabalhos meus em aço da série Grades de 2008 (o maior está participando da exposição Jogos de Guerra no Memorial da AL, SP) e uma escultura em madeira pintada do Sol LeWitt de 1966. Peguei a foto do Sol aqui.

Em processo

ENTRE – Sergio Porto, Rio

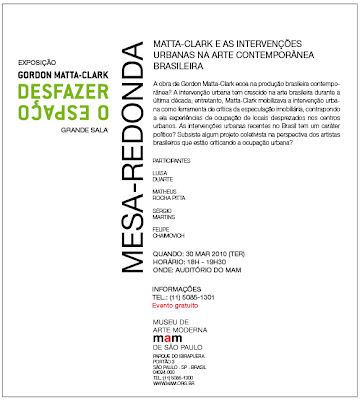

Matta Clark – MAM, SP

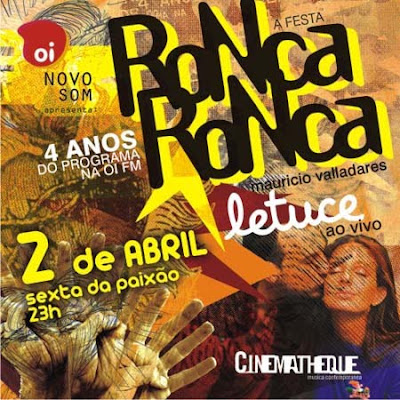

RoncaRonca – 4 anos na Oi Fm

Design cidade: em construção

Ativo na Rua – uma letra para som sem voz

Ativo na rua

Um radar faminto

Engatilha e fuzila

Atento na rua,

Um olhar parado

Cheira dejetos visuais

E acha entre as aspas

Os ascos, as farpas

O olhar agora anda e acha cores e formas

Espremidas serenas no monte de lixo

(Sacos rasgados, odores vazados, moscas em vôos preguiçosos)

Andávamos na rua e vimos

Reluzentes por demais,

Sufocantes, sensuais,

Um pedaço de ódio

Um naco de amor

Um pé solitário

Um objeto em pó

Folhas de compensado

Um tempo abandonado

Uma vida partida

Um pêssego com a pele rasgada

Vimos entre os ossos urbanos

A cloaca das formas

A bacia das almas

A basura de asas

Voando sobre as casas

Na secura serena do dia quente na Lapa.

No dia 7 de janeiro Fred Coelho passou no ateliê para trocar idéias. Depois vagamos pelas ruas da Lapa embaixo do calor infernal que assolava a cidade. Um música tocou no ar. Só som, sem voz humana. Paramos no boteco da esquina. Ao lado uma pilha de lixo. Na escada de azulejos do Selaron um monte de gringos fotografando. Rabiscamos no papel a letra para uma música que não existe ainda. Achei ela aqui agora e resolvi subir junto com as fotos daquela tarde.

Campos Campo Calacanhoto IMS, Rio

Grande Jupiter

Ontem gravei o programa Radar do Leo Felipe na TVE e o Camarote da Katia Suma na TvCom. Papo rápido para divulgar a exposição na Subterrânea. Os 2 programas misturam atrações musicais com entrevistas ao vivo. No Camarote tive a sorte e o prazer de esbarrar com o extraordinário Jupiter Maça enfileirando 3 canções em inglês com uma banda baixo quitarra e bateria afiadíssima.

Balanço Geral na Subterrânea

Quinta, sexta e sábado em Porto Alegre

Balanço Geral é a exposição que inauguro na quinta, 25 de março, às 19h, no Atelier Subterrânea (Av. Independência, 745/Subsolo – Porto Alegre).

Na sexta, 26 de março, das 16h às 19h, acontece o Seminário Iniciativas alternativas de Inserção no Circuito de Arte, no Santander Cultural. A proposta do seminário é ampliar os intercâmbios culturais e o fortalecimento do circuito independente de artes.

No sábado, 27 de março, às 16h, rola uma mesa redonda com mediação do crítico e curador Felipe Scovino no Atelier Subterrânea (entrada franca).

A exposição fica na Subterrânea até 17 de abril de 2010.